The Basel Committee has decided that banks can net certain transactions when calculating the leverage ratio. This will bring the regulatory requirement closer to US rather than to European accounting standards.

In January 2014, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision modified the crucial leverage ratio requirement that will be included in the Basel III prudential rules. The leverage ratio is intended to be a backstop measure of pure asset size compared with the bank’s Tier 1 capital, and the minimum level is set at 3%.

The latest changes mean that banks will be able to net out certain transactions in calculating their asset size, including securities financing such as repurchase deals with the same counterparty, trades on behalf of clients that are cleared with qualifying central counterparties, and cash held for paying variation margin on derivative trades. The effect of these changes is to bring the regulatory requirement closer to US Generally Agreed Accounting Principles (GAAP), which allow netting of certain trades. By contrast, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) championed in Europe do not allow such netting.

The difference in accounting standards effectively means that the reported sizes of US and European bank balance sheets are not directly comparable. US bank balance sheets appeared smaller, prompting complaints from European banks that they faced an uneven playing field, and pressure for the US to adopt IFRS. The decision to allow derivatives netting for calculating the leverage ratio should now benefit European banks, although it means their Basel reported balance sheet would be different from the IFRS version.

Lower leverage

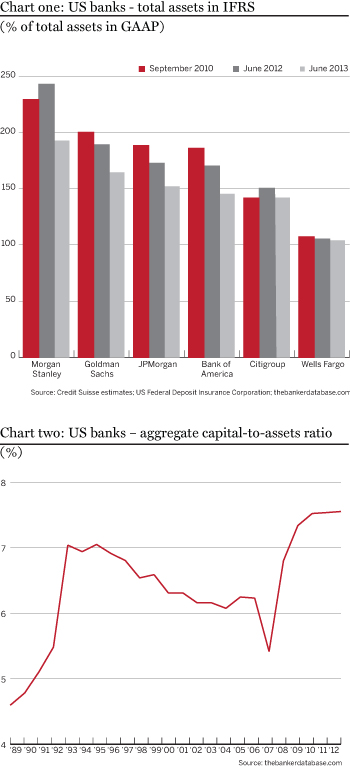

Research by Credit Suisse in 2010 provided some estimates of US bank balance sheet sizes using IFRS rather than GAAP, and the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has since provided full data on IFRS calculations for mid-year 2012 and 2013. Integrating these reports together suggests that the composition of US bank balance sheets had in any case been changing (see chart one). The differential between GAAP and IFRS asset sizes fell by about $30bn to $40bn at the leading banks between 2010 and 2013, implying a sharp reduction in total derivative positions.

The exceptions are Wells Fargo and Citigroup. Wells Fargo had always pursued a more plain vanilla corporate banking model without the same degree of derivative trading, while Citi had to begin its balance sheet reduction in 2008 after its rescue by the US government. It also has the largest global retail banking presence of the leading US banks, a business line that would not show such a substantial difference in asset size between the two accounting standards.

In any case, whether by astute use of netting or by genuinely increasing capitalisation, US banks have been moving toward healthier leverage ratios for two decades (see chart two). This was punctuated by a sharp deterioration in 2007, when the largest US banks began to suffer heavy losses related to subprime mortgage securities, but had not yet begun to recapitalise in the way that they did after 2008. By the end of 2012, the aggregate leverage ratio for the largest 64 US banks in The Banker Database, accounting for assets of more than $11,000bn, had reached 7.6%. This compares with 4.6% in 1989, and 5.4% in 2007.