Considered the birthplace of quantitative easing, Japan is a testing ground for the unconventional monetary policies being adopted by central banks around the world. Danielle Myles looks at how its banks are faring.

This September, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) will conduct the first comprehensive review of its controversial quantitative easing (QE) programme. Encompassing record low interest rates and a government bond-buying programme, QE – along with a stimulus package and structural changes – is part of a three-pronged economic policy dubbed ‘Abenomics’ after its instigator, prime minister Shinzo Abe.

Launched in April 2013, its goal is to spur lending – and therefore spending – to kick-start economic growth in the country and increase inflation to 2%. Despite successive expansions of the policy, to date Abenomics has failed to hit those targets. This is reflected in the balance sheets of the country’s banks, key players in delivering the Abenomics plan.

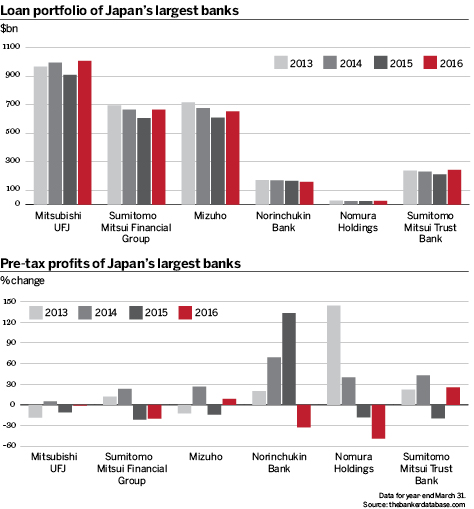

After keeping interest rates at 0% for years, in January 2016 the BoJ took the historic decision to move into negative territory, dropping rates by 10 basis points. Based on the loan portfolios at Japan’s six biggest lenders, 0% rates had not encouraged lending; with the exception of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, which saw a slight rise in 2014, their holdings dropped year on year from 2013 to 2015.

Mizuho Financial Group saw the biggest change, with its loan book shrinking 14.79% over the two-year period. At Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank that figure was 10.82%, while at Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group it was 12.73%.

That said, 2016 has seen a slight improvement. With the exception of Norinchukin Bank, Japan’s top-tier lenders have all expanded their loan portfolios over the 12 months to March 2016. The most impressive gains were made by Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank (up 14.9%) followed by Mitsubishi UFJ (10.92%) and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (9.56%). Mizuho Financial Group’s loans grew 7.07% and Nomura Holdings’ 7.41%.

While this turnaround may please the BoJ and Shinzo administration, the banks are more interested in how it affects their interest income. To keep their profit margins intact, banks must be able to charge higher interest rates on loans than deposits. From 2013 to 2015, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group and Mizuho were among the best at mitigating the damage from shrinking loan portfolios; their net interest income dropped by 12.73% and 14.79%, respectively, markedly less than their loan portfolio changes. Mitsubishi UFJ’s interest income dropped by 5.87%, in line with its loan holdings. However from 2015 to 2016, this revenue stream has failed to increase at the same pace as their loans. Mizuho’s interest income over that 12 months actually fell by 5.23%.

Looking at the bigger picture, Japanese banks’ profitability has been uneven since Abenomics was first launched. With the exception of Norinchukin in 2015 and Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank and Mizuho this year, the six biggest banks have posted losses for the past two years. Nomura is among the more notable, down 49.21% this year and 18.35% last year.

Some eurozone-headquartered lenders have criticised the European Central Bank’s negative interest rates for hitting their profitability. Japanese banks have been less vocal, but a recent Fitch report identifies negative interest rates as one of the reasons the country’s lenders will continue to face profitability pressure.

Data for this story was sourced from www.thebankerdatabase.com.