Non-financial firms are increasingly parking their tanks on the lawns of traditional, mainstream banks, with a massive growth in lending from car manufacturers and supermarkets, especially. Can these operations disrupt the banking market, or will they be undermined by weak parent entities?

On September 18, 2015, when the US Environmental Protection Agency announced that Volkswagen had been cheating about the emissions output of its diesel engine cars, much ink was spilled questioning the future of one of the world’s biggest car manufacturers.

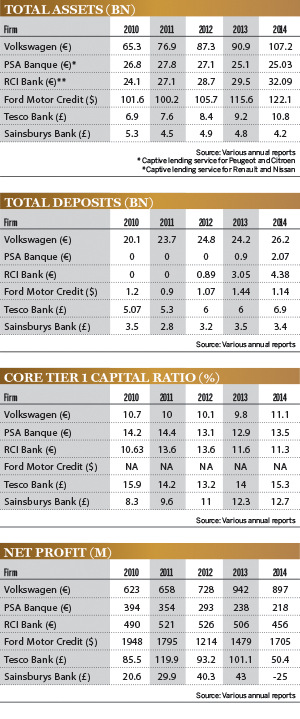

Less focus was placed on the fact that looming behind Volkswagen’s production lines is a large and fast-growing financial services unit that extends financing to individual customers and dealerships, and has within it a fully fledged and licensed bank. Total assets at Volkswagen Financial Services (VFS) grew from €65bn in 2010 to €107bn in 2014, and, as of that date, it had customer deposits worth €26bn, a cost-to-income ratio of 60%, and a net profit of almost €900m.

Motoring ahead

Growth rates at other financial services units run by corporations have been similarly impressive in recent years (see table). Such institutions generally come in two flavours – so-called ‘captive’ institutions run by large manufacturers such as Volkswagen, where the express purpose is to help expand the customer base for the product of the parent entity, and more run-of-the-mill retail banks established by supermarkets as an independent and relatively unconnected adjunct to the primary business. Both have stepped up in recent years, just as the major traditional banks have had to cut their cloth around constraints imposed by new regulations and new cost pressures.

“We set up a dedicated non-bank financial institutions team for Europe, the Middle East and Africa a few years ago, partially to deal with the growth in this very sector: corporates offering up financial services or bank-like products, or often setting up a fully fledged banking arm. There is now space for both traditional and non-traditional banking in developed markets, and the latter encompasses a growing range of activity,” says Erwin van Lumich, managing director for financial institutions at Fitch Ratings in London.

This rapid growth provides a useful lending outlet for the real economy as the activity of traditional banks becomes more constrained. However, automotive lenders and supermarket banks face the risk not just of their loans going sour, but also the possibility that the normal business of their parent entity hits hard times, or disappears altogether. Even before the emissions scandal broke, Volkswagen’s overall operating margins lagged behind its major competitors. Operating margins for its passenger vehicle division, one of its largest, hit just 2% in the first quarter of 2015.

Taking the risk

As is the case with many ‘captive lenders’ in the automotive market, Volkswagen Financial Services is a stand-alone, independently rated entity, that raises its own financing through the capital markets or deposits. So, there is a useful firebreak between the manufacturing and financial sides of the business. However, the predominant purpose of all such financial services units is to help drive car sales for the parent entity by financing solutions to both customers and dealers. In the UK, 80% of individual car purchases are fuelled by financing, and 90% of that financing is offered by the manufacturer itself. While financing to car buyers is secured by the physical vehicle, financing to dealers is often made on an unsecured, wholesale basis. If sales tumble, risks will inevitably increase.

“If the creditworthiness of a parent entity, whether it is an automobile manufacturer, a supermarket or something else entirely, is reduced, it often has negative implications on our rating for its financial services entity. The rating impact may depend depend on how strategically important the financial services section is, or, for example, on whether or not the parent company could easily live without the financing arm. In the case of car makers, offering financing solutions is a hugely important part of actually selling cars,” says Mr van Lumich.

On other occasions, a failure on the financing side could deal a deadly blow to the parent entity. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the financial services division of General Electric, GE Capital, made up a larger and larger part of the overall company as the traditional manufacturing activities waned. GE Capital was vast, supporting anything from aircraft financing to store cards at retailer Wal-Mart, and at one point contributed half of the firm’s overall profits. A series of poor acquisition decisions in the run up to the financial crisis, and the impact of the economic downturn on many of its core financing operations, pushed the division into a string of poor results, weakening General Electric in turn. GE Capital was forced to dramatically slim down in the aftermath of the crisis, and now it is being wound down almost completely, with most of it chopped up and sold on to other market participants.

Supermarket sweep

The strategic links between supermarkets and the banks they have established are arguably less concrete than those in the captive finance space. However, banking services are increasingly forming a valuable part of the overall brand for larger retailers, especially as they lose market share in simple grocery selling to smaller and cheaper competitors.

Due to their focus on smaller scale retail banking, supermarket lenders are generally smaller than their automotive financing counterparts (see chart), and have historically hitched themselves to the wagons of larger commercial banks. In the case of M&S Bank, an offshoot of UK retailer Marks & Spencer, it started life in 1985 as St Michael Financial Services, launching an in-store charge card. It gradually added personal loans, savings accounts and insurance services to its product range before being renamed M&S Money in 2003 and sold to HSBC the year after. It became M&S Bank in 2012, and is maintained as a joint venture with its parent retailer.

From M&S’s perspective, this is an attractive deal. HSBC does most of the heavy lifting in terms of software systems, product development and capital, while all the retailer needs to do is look after the branding and make some space in a few of its stores for the bank branches. In return, the profits from M&S Bank are split 50-50, a nice fillip for M&S’s often-patchy retail performance. Better still, this arrangement is slated to last until at least 2019.

“There is a very close relationship between M&S Bank and M&S in general. The bank has been run as a joint venture between the two since 2004. The frequency of engagement between the senior management in both organisations is very high, with quarterly executive committee meetings and monthly general management updates,” says Paul Stokes, head of products at M&S Bank.

Other competitors are run on slightly different models. Tesco Bank started life in 1997 as a 50-50 venture between the retailer at the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS). In 2008, Tesco bought RBS out, and the bank is now a wholly owned subsidiary with its own banking licence. Sainsburys Bank was also formed in 1997, this time as a joint venture with Bank of Scotland. Sainsburys took full ownership of the bank in 2014.

Saving grace

The UK’s supermarket banks are looking ever more like their mainstream retail rivals. M&S Bank was the first to offer a current account service in 2012, followed by Tesco Bank in July 2014.

“We have just shy of 4 million customers in the UK, and offer products spanning all aspects of retail financial services – current accounts, loans, credit cards, insurance, and bureau de change services,” says Mr Stokes at M&S Bank.

Mr Stokes is coy when asked whether supermarket banks could directly challenge or even supplant the UK’s major retail lenders, but, given the growth it has seen in recent years, that is clearly a possible direction of travel for the sector. The UK government has recently made it much easier for customers to switch between banks, and online banking means that millions of people can be reached without the costs of setting up an extensive branch network. If customers do want to speak to someone face to face, supermarket bank branches often stay open as long as their host stores, giving them a big advantage over the relatively sleepy branch operations of the larger banks and building societies.

Captive lenders in the automotive sector are also offering more and more retail banking services alongside the usual vehicle and dealer financing. Deposit taking has expanded significantly over the past five years among Europe’s three largest automotive financing arms (see chart) – Volkswagen Financial Services, PSA Banque, which is owned by Peugeot and Citroën, and RCI Banque, which is fully owned by Renault but also offers financing for Nissan cars in Europe and South America, thanks to the cross-ownership structure of the two firms. Though Ford Motor Credit is not incorporated as a bank in the US, its subsidiary, Ford Credit Europe (FCE), is licensed as one in the UK. FCE does collect customer deposits, but the overall value of these is relatively small.

"This year, we became the first UK automotive finance provider to establish savings accounts – both an instant access account with a very competitive rate and one-, two-, and three-year savings bonds,” says Steve Gowler, chief executive of RCI Bank, the UK subsidiary of RCI Banque. “The service is based on a model already operated by RCI Banque in France, Germany and Austria, and is intended to make the group less reliant on capital markets funding, which can be unreliable during market stress. As far as further diversification is concerned, we haven't ruled anything in or out. We have no specific plans to offer current accounts, but it might be something we look at in the future."

As with any new entrant to a market, staying power will perhaps be the most useful skill to acquire. “Non-traditional banks are often very capable of gathering deposits quite rapidly, but it comes at a cost, because they often have to offer rates above that available from mainstream banks," says Mr Gowler. "We have to look out for how sticky these deposits are. One of the reasons why, in general, non-traditional banks are rated lower than their mainstream counterparts is that they are often significantly smaller and less diversified. However, ordinary banks face huge challenges around profitability. Smaller competitors are often able to grow the riskier elements of their product range far quicker than established players.”

Sticking to the rules

In the end, financial services arms, be they captive lenders or supermarket banks, will run up against the same regulatory restrictions as traditional banks if they want to compete on the same playing field. “It’s important to emphasise that these are regulated entities. That means they will have to comply with the latest Basel reforms, such as higher capital requirements and liquidity ratios,” says Salla von Steinaecker, a director at Standard & Poor’s ratings services.

Liquidity ratio compliance will be a significant challenge for the captive lenders. Under the Basel III reforms, banks must comply with both the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), and the net stable funding ratio (NSFR), respectively short- and long-term measures designed to shift the sector to a more robust funding model. Meeting the standards set down by the NSFR, which rewards institutions with large, stable deposit bases, will be particularly tricky for institutions more traditionally reliant on capital markets funding.

“Captive finance institutions, similar to other credit institutions, don’t generally publish their LCR or NSFR compliance yet. In many cases, their individual liquidity ratios are quite weak, especially when compared with those of commercial banks. Some captives in the automotive sector have begun taking retail deposits, which will help meet the NSFR especially, but there is still a lot of work to be done to build up those ratios,” says Ms von Steinaecker.