The world has come a long way since the lurid headlines of 2008 warning that support for the banking sector would cost governments around the world trillions of dollars. While dangers still persist, money is steadily starting to return to government coffers. Writer Geraldine Lambe, Research Geraldine Lambe and Guillaume Hingel

Click here to view an edited video

In November 2008, ABC News warned US taxpayers that government support for the country's financial sector would cost up to $7500bn. It cited figures from macroeconomic analysis firm Bianco Research showing that, in 2008 dollars, the cost of the bailout would be more than the combined costs of the Marshall Plan, the Louisiana Purchase, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the entire historical budget of NASA, including the moon landing. Other, less sensational figures from that month still put the cost of the US government's intervention in the financial system at $3500bn, representing about 25% of the goods and services produced in the country in 2007.

By April of this year, the expected cost was much less dramatic. In a letter to US Congress, treasury secretary Timothy Geithner said the net cost to the US taxpayer is likely to be $89bn - still significant, but less than 1% of gross domestic product (GDP) and less than the cost of the savings-and-loan crisis in the 1980s and early 1990s, which totalled about 3.2% of GDP.

As recently as December 2009, the cost ascribed to the UK taxpayer for the government's bank rescue package was £850bn ($1325bn). By the time of the UK's June 2010 budget, the UK Treasury had reduced the likely net cost to the taxpayer to no more than £2bn.

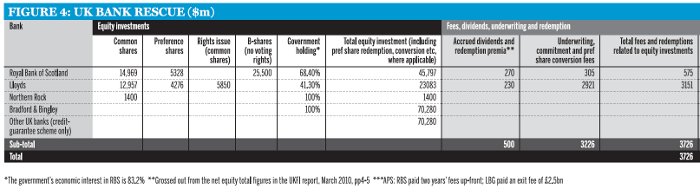

After UK banks' first-half results were reported at the beginning of August, the figure quoted in the June budget does not look too wide of the mark. For those banks that sought emergency capital from the UK government in 2008, the change from last year could not have been more stark. Lloyds Banking Group, 41.3% owned by the UK taxpayer, reported a pre-tax profit of £1.6bn, compared with a loss of £4bn in the same period a year earlier. Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), in which the UK government has an economic stake of 83.2%, reported a pre-tax profit of £1.4bn, a swing of £5bn from the £3.4bn loss a year ago.

UK consultancy the Centre for Economics & Business Research is so impressed by the turnaround in the country's banks that it has predicted the UK government will make a profit of £19bn on the bank bailouts.

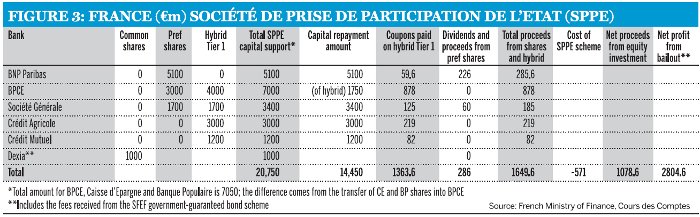

The French government has already declared a profit on its intervention in the financial sector. Having placed a self-imposed cap on the amount it could make from its capital injection, the government nonetheless turned in a profit of almost €1.1bn.

The explanation for the discrepancy between the shocking figures of 2008 and the more measured costs or even profits now being touted, lies somewhere between lurid reporting, a recovery in the credit and equity markets, and the treatment of debt guarantees or asset protection as government loans.

Watch the videoTrue costs of the bailout decision |

Treasuries get returns

Recent figures from government accounts and from the entities managing investments and loans on behalf of taxpayers reveal that money is steadily coming back to government coffers, insured assets have yet to cost the taxpayer anything and some troubled asset portfolios are tentatively beginning to recover some value.

In the UK, for example, the taxpayer's final equity investment (following preference share conversions, rights issue take-up, etc) of £68.88bn in RBS and Lloyds, has generated combined fees of £3.72bn from accrued dividends and redemption premiums, and underwriting, commitment and preference share conversion. Not including the value of the banks' shares (on which, if the government sold today - although it probably could not - it would make a profit of about £5bn) that is a return of 5.4%.

The July annual report from UK Financial Investments (UKFI), the entity created to oversee government investment and ownership, shows the UK taxpayer sitting on a paper profit. UKFI says the weighted average of price paid per Lloyds share by the government was 73.6p. Once all the fees and premiums are taken into account, the net cost of the government's support for Lloyds is equivalent to 63.1p per ordinary share. On August 6, Lloyds shares were trading at 76.3p.

For RBS, the recovery comes from a lower base. According to UKFI, the weighted average of all the UK government's investment prices was 50.2p. Net of fees and premiums, that cost is reduced to the equivalent of 49.9p per ordinary share. On August 6, the day RBS reported its first-half results, its shares were trading at 53.1p, up 61% over the past six months and up 2.12% on the FTSE 100.

Tarp payback

In the US, money is also beginning to come back to the Treasury. The July report from SIGTARP, the body monitoring the various programmes under the umbrella of the Troubled Asset Relief Programme (TARP), revealed that, as of June 30, 87 TARP recipients had repaid all or a portion of their principal or repurchased shares, for a total of $201.5bn returned to Treasury. This leaves a total of $182.5bn of disbursed TARP funds outstanding.

By the same date, the latest available data as The Banker went to press, the US government had received $15.7bn in interest, dividends and other income, and $7bn in proceeds from the sale of warrants and stock received as a result of exercised warrants.

The Banker's analysis of money that has only been disbursed to and paid back by US banks (excluding the $47.5bn capital injection into insurer American International Group [AIG] and the $79.6bn given to the automotive industry, as well as others) is more revealing.

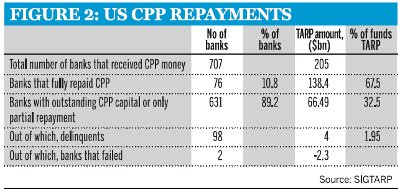

Of the 707 banks to receive almost $205bn in TARP funds through the Capital Purchase Programme (CPP), 76 have fully paid back their funds to a total of $138.4bn. This means 10.8% of banks have fully repaid 67.5% of the funds invested in banks by the US government. This leaves 89.2% of banks responsible for repaying the remaining 32.5% of funds outstanding - and 580 of these owe less than $100m to the government (see figure 2).

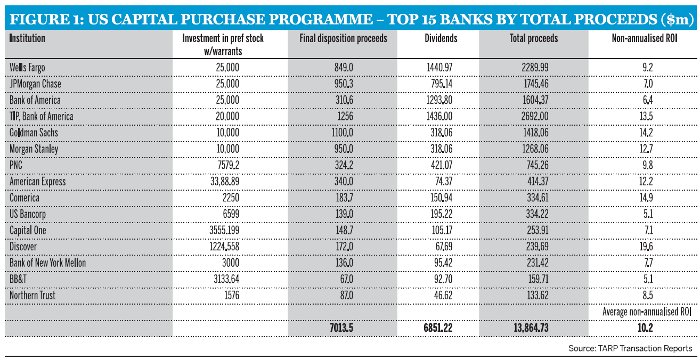

Returns on those TARP investments already repaid in full have been high. The top 15 by total proceeds have yielded an average non-annualised return of 10.2%. Individually, the highest is Discover Financial Services, which yielded a non-annualised return of 19.6%, followed by Comerica at 14.9% and Goldman Sachs at 14.2% (see figure 1). On an annualised basis, the return on Goldman's $10bn TARP funds becomes 20%.

Investment in Citigroup, yet to fully repay its TARP funds, is nonetheless yielding good returns for the US taxpayer. Including funds from the Targeted Investment Programme (TIP), through which Bank of America and Citigroup each received a further $20bn of government capital, the interim, non-annualised return on investment based on the amount repaid by Citi so far is 15.91%.

Timothy Geithner, US treasury secretary

Guarantees and protection

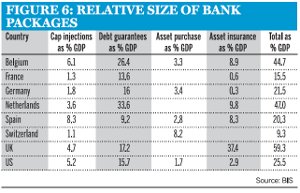

In terms of amounts promised, asset protection schemes and debt guarantees played a significant role in many governments' rescue packages.

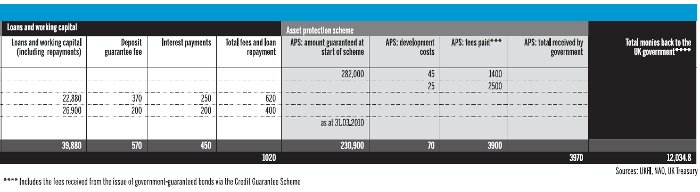

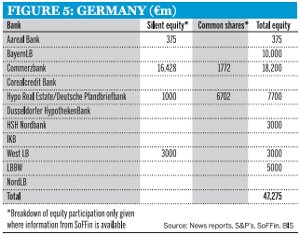

In Germany, for example, the government's debt guarantee scheme totalled €163bn, versus the €47bn the federal and regional governments say they have injected into the country's banks. In the UK, such schemes represented at least £450bn of the £850bn bailout price tag (a further $200bn was represented by the Bank of England's Special Liquidity Scheme).

While these schemes helped to swell the headline numbers that grabbed public attention, they did not add an immediate cash cost to governments.

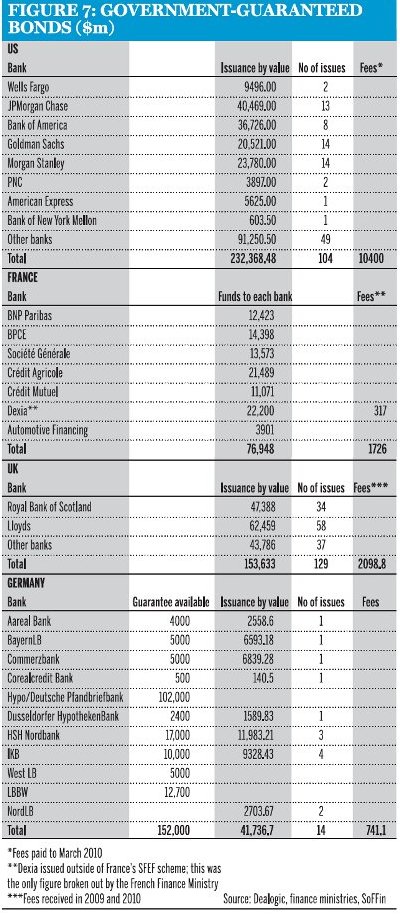

Each scheme varies in form and fee structure. To issue government-guaranteed bonds in Germany, each bank pays a 0.1% fee on the total amount guaranteed and an additional fee ranging from 0.5% to 2.1%, depending on the duration of the bonds. Under the UK's Credit Guarantee Scheme, banks pay a per-annum rate of 0.5%, plus 100% of the median five-year credit default swap spread during the 12-month period that ended July 1, 2008. In the US, fees for participation were based on the maturity of debt issued and ranged from 50 to 100 basis points (annualised); a surcharge - of 10 to 50 basis points - was imposed on debt issued with a maturity of one year or greater after April 1, 2009.

The debt guarantee schemes - which have so far seen no defaults and for which governments have not set aside capital - are generating significant fee flows. While no governments break out the fees paid on a bank-by-bank basis, many have provided total fees paid since the schemes started. In total, US banks have paid $10.4bn, UK banks just over £2bn, and German banks just over €700m.

The French government's specially created entity, Société Financement de l'Economie Française (SFEF), represented a different approach to government guarantees. SFEF issued AAA rated, government-backed bonds, then channelled the funds to recipient banks in return for collateral. SFEF raised a total of almost €77bn, which it passed on to the banks. According to the French finance ministry, the total fees received from the scheme, including a fee from Dexia, that issued bonds outside of the SFEF scheme, are just over €1.7bn (see figure 7).

Where information is available, asset-protection schemes are also generating fees, but not yet costing money. In return for providing protection under the UK's Asset Protection Scheme (APS), the government has so far received fees of £1.4bn from RBS - whose are the only assets included in the scheme - and £2.5bn from Lloyds. While it ultimately elected not to participate, Lloyds was judged to have benefited from an implicit government guarantee between the APS's announcement and its actual establishment, so was charged an exit fee. Nor did the government have to pay for the start-up costs, for which RBS was charged £45m and Lloyds £25m.

Although the annual report from the UK's Asset Protection Agency reveals that writedowns have already absorbed £30bn of RBS's £60bn first-loss buffer, it has also reduced the amount covered by the scheme from £282bn to £230bn. Chief executive Stephan Wilcke is on record as saying that the APS will likely yield a £5bn profit for the taxpayer.

Writedowns may write back

In the dark days of late-2008, the recovery of troubled assets looked impossible. The panic about the whereabouts and plummeting value of subprime assets paralysed markets and pushed other asset values perilously low. Non-subprime but illiquid assets suffered drastic writedowns. Recent valuation increases show that illiquid does not necessarily mean toxic; and that writedowns may be written back.

A portfolio valuation released on July 28 by Maiden Lane portfolios - three vehicles created to take bad assets from Bear Stearns and AIG - revealed that unrealised gains, the difference between the market value of their securities and the outstanding amount of the authorities' loans to the vehicles, stood at $10.8bn.

Maiden Lane II and III - the two vehicles that relieved AIG's balance sheet of billions of troubled assets - had been showing a paper profit for some time. However, in the last week of July, Maiden Lane I, a $30bn portfolio that took Bear's worst assets so its acquisition by JPMorgan Chase could proceed in March 2008, also moved into the black. While the securities' illiquidity means a rapid sale is unlikely, the gains mean, on paper at least, the Federal Reserve could exit its positions and repay the loans, which have maturities of between six and 10 years.

Asset prices were also showing signs of recovery in Europe. In early August, the two UK banks taken into 100% government ownership at the height of the crisis also reported some positive results. Bradford & Bingley's legacy mortgage book, all that remains in government hands since its branch network was sold off to Spanish bank Santander, made a pre-tax profit of £896m for the six months ending June 30, compared to a loss of £160m a year earlier.

At Northern Rock, the 'bad' bank - the closed mortgage book hived off into Northern Rock Asset Management (NRAM) to make way for the sale of Northern Rock - outperformed the 'good' bank. NRAM, currently being merged with Bradford & Bingley's mortgage book, recorded a pre-tax profit of £349m, compared with a £724m loss a year ago. Northern Rock, with £20bn of deposits and £10bn of mortgages, recorded a £142m loss.

Despite what many imagined when both banks were taken into government ownership, UKFI says that 90% of the assets from Bradford & Bingley and NRAM are "fully performing", meaning that customers are not in any arrears. If the definition is broadened to include loans not in arrears over three months, 95% of the mortgage book is "performing".

There was more good news when BNP Paribas reported its earnings at the beginning of August. For the first time since the second quarter of 2007, gains in the value of the bank's troubled assets had exceeded new provisions. While the gain of €61m does little to offset the billions of euros BNP Paribas has written down, many see this as further evidence that asset valuations have stabilised and may be in the early stages of recovery.

A way to go

If the figures look much better than they did almost two years ago, some major caveats remain. For one thing, paper profit is not a realised gain, and fears persist about the potential of assets such as commercial mortgage-backed securities to go down in value.

Government exits from partially or wholly owned banks in many countries look some way off. In some cases it is because governments are holding on to get the best return for taxpayers' dollars. In others, such as Ireland, banks and the financial system are in no condition to be weaned off government life-support. Bank of Ireland recently reported another €1bn loss, and Anglo Irish Bank has received a further €10bn in government support. This is affecting the cost of government debt. The premium investors demand to hold Irish 10-year debt rather than the German benchmark widened 10 basis points to 303 basis points in mid-August, bringing it close to the record of 316 points reached on May 7.

In Germany, many of the precise details remain unclear about who is on the hook for what. The IKB losses absorbed via state-owned KfW before IKB was sold to Lone Star are unknown (as is the price paid by Lone Star), but estimates suggest it could be about €8.5bn. Equally, while SoFFin has so far posted a profit, it has unrealised losses from the writeoffs for its holdings in HypoRealEstate, which are expected to be €4.3bn.

Moreover, most argue there is yet little appetite to soak up the many billions of assets currently being managed on behalf of governments. Similarly, current market sentiment may make it difficult for the private sector to absorb the assets in special liquidity schemes.

Again, in Germany, the details about asset protection schemes are vague. Regional governments are reported to have given their Landesbanken first loss asset guarantees of €27.7bn, but the value of the guarantees provided to WestLB through the spin-off of assets into a €77bn bad bank could be higher. This is currently being investigated by the European Commission. Nationalised HypRealEstate also plans to shift about €210bn of assets into a bad bank in the second half of 2010.

Equally, while the majority of CPP investments have been repaid - at a significant profit - the US Treasury has posted a $2.3bn loss on two investments, and three TARP recipients are failed institutions. Some 98 institutions failed to make the most recent CPP dividend payments. Still, to put that in perspective, these 98 banks represent only 1.9% of CPP funds outstanding.

The US problem

The biggest question marks for the US are its outstanding investments in and loans to the automotive industry (in which the government still has about $70bn invested, and on which it has so far received $2.3bn in dividends and interest), AIG and in the housing behemoths Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

However, AIG is gradually reducing its debt to the Federal Reserve. At the end of July, data showed that the company had cut its draw on a credit line from the Fed by about $3.5bn in the previous three months, signalling an improvement in its liquidity. The data also showed that the draw had declined for 10 of the previous 12 weeks for the first time since the credit facility was established in 2008. It has about $20bn in loans outstanding to the Fed and CPP funds outstanding of $47.5bn.

Moreover, AIG's restructuring is well under way (in March it sold Alico for $15.5bn and three more units are lining up for sale or listing) and the profit and loss sheet is looking more healthy. While AIG reported a $2.7bn loss for its second quarter of 2010, this stemmed from a $3.3bn charge related to the sale of Alico. Excluding that charge, AIG reported $1.3bn in profit and $2.2bn in operating income. Both figures showed significant improvement over the same time last year.

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae represent the biggest problem, both financially and structurally. Even the most modest projections suggest the price tag for government support could be close to $200bn. The US government owns 80% of the two firms and has extended nearly $150bn in lines of credit in order to prevent further destabilisation of the US mortgage market, in which the two companies provide financing for nearly 90% of the nation's home loans. Many argue that government policy to extend home ownership to low-income families, enacted through the two firms, was the major cause of the subprime crisis in the US, so reform of their role in the market is seen as crucial to overall financial stability. However, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were not dealt with in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill.

But even here there is some good news. On August 5, Fannie Mae reported its smallest quarterly loss in three years, suggesting it may need less government aid than had been expected. The firm lost $1.2bn in the second quarter of 2010, compared with a $11.5bn loss in the first quarter and a loss of $14.8bn in the second quarter of 2009. Freddie Mac has yet to report second-quarter earnings.

Funding crisis

Despite the return to health for many of the world's largest banks, concerns persist about the sustainability of the overall banking recovery because of huge funding requirements.

Rating agency Moody's has warned that as fiscal cutbacks begin to bite, more loans will go bad, particularly in countries such as Spain, and that many banks will struggle to raise new finance as existing loans fall due. With government debt guarantee programmes and special liquidity schemes either closed or closing, replacing this debt is a major concern.

Recent reporting by the banks, showing that many have either completed their 2010 funding programme or are well on track to do so, have eased even some fears about near-term funding at least.

For example, Barclays Bank, Commerzbank, Danske Bank and Dexia all stated in their second-quarter results that their term funding programme for the year is complete. Similarly, BNP Paribas says it has completed three-quarters of its 2010 term-funding needs, and RBS says its has completed 70% of its 2010 £20bn to £25bn programme. Lloyds is also on track with £18bn completed this year, only £2bn short of its £20bn to £25bn funding target.

The Spanish cajas may be struggling, but BBVA said in its March financial report that it had covered a large part of its estimated funding needs for 2010, and Santander has raised almost €20bn. Both have also significantly increased deposits.

The funding crisis that was predicted in May and June, when access to senior and subordinated markets was shut, may have been averted, but concerns remain about smaller eurozone banks and requirements for 2011, when UK banks alone must raise £390bn in new debt. Moreover, according to rating agency Fitch, weaker banks are still struggling to borrow funds with tenures longer than one month and some smaller banks are unable to borrow in the interbank or the commercial paper market, in what has become a two-tiered interbank European market.