Funding from capital markets has released development banks from the constraints of national economies' budgets to invest in a plethora of projects ranging from infrastructure, exports, business start-ups and the social development and growth of transition economies.

Click here to view an edited video

If the role of development banks was being questioned in the buoyant years preceding the financial crisis - backed by the theory that the markets could generate the economic impetus needed to help emerging countries - that is certainly not the case now. The financial earthquake that left no market in the world unshaken created an unprecedented scenario, in which most macroeconomic indicators collapsed and very limited credit was available to businesses and individuals. The less wealthy governments in the world would have found themselves with no viable tools to support their economies were it not for multilateral agencies' emergency funds.

KFW to the rescue

This, unfortunately, is also true in the developed part of the world. The future of Greece hangs on a €110bn EU/IMF bailout, which includes a substantial contribution from Germany, made through national development bank KfW. This loan is expected to total €22.4bn over three years.

KfW was proud to announce that it was ready to render this service to its government, and that its €75bn fundraising plan for 2010 would not need adjusting. It will not even need to launch a special funding programme as its national and international investors are always offered a broad range of products. Its main source of funding is the capital markets.

"The advantage of using the capital markets is that you won't be influenced by the state of the economy of your shareholders," says a senior official at a regional bank. "When you rely on budgets of national economies, or maybe on some other local banks, [just] when you need financing for projects you [shouldn't find yourself in a situation where] shareholders say: 'there is a crisis, see Greece, we can't invest any more money in your capital'."

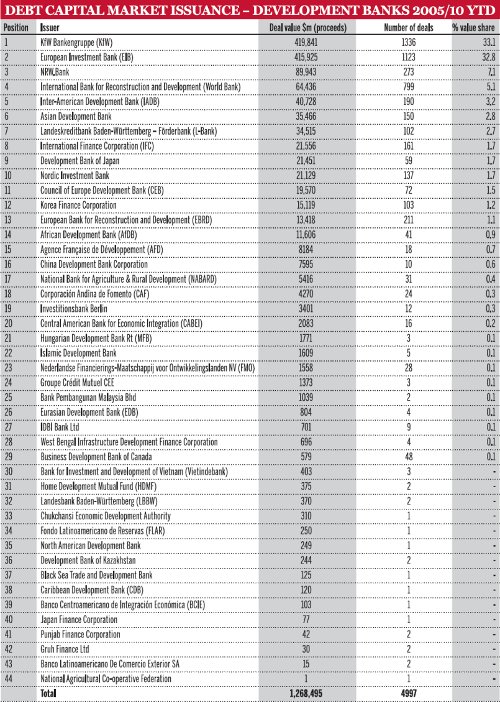

With a €400bn balance sheet at the end of 2009, a AAA rating from the three main rating agencies and a zero-risk weighting of KfW's bonds and notes, the bank is a name the international capital markets are used to seeing. It tops the league table of development banks' issuances, according to data provider Dealogic, with a total of almost $420bn raised over the past five years.

Frequent use of capital markets has fuelled its activities both nationally and in the region, financing infrastructure projects, exports, business start-ups, social development and growth of transition economies. Almost 80% of its efforts are in the EU.

Its frequent use of the debt capital markets (DCM) has also helped, securing an impressive €75.3bn in 2008, with almost 90% of it coming from benchmark bonds and public issuances.

KfW is a unique example, but a few large multilateral development agencies enjoy a similar standing on international markets and are generally seen as a safe bet, particularly in a world where the US markets are convalescent and the prognosis on Europe looks increasingly worrying.

"The biggest risk in the world at the moment is European sovereign risk," says Philip Brown, head of sovereign, supranational and agency debt capital markets at Citigroup. "Multilateral development banks [MDBs] are outside any kind of contagion at the moment."

Not all agencies have the financial muscle and capital markets appeal of KfW, however, and the financial crisis has stretched the capacity of many development banks.

Despite access to DCMs by the big multilateral agency names, many still have to depend on countries' contributions to their capital as the main way of raising funds.

Watch the videoDevelopment banks |

AfDB stretched

In Africa, the already growing demand for funds has been exacerbated by the crisis, as commercial banks' smaller balance sheets and almost non-existent appetite for lending means that even good infrastructure projects are on hold. To respond to this need, the African Development Bank (AfDB) increased its levels of operations by four times last year compared to 2008, to 5.6 billion special drawing rights (SDR), the equivalent to $8.2bn.

During 2009, the AfDB more than doubled its financial approvals to almost $12.7bn, from $5.4bn in 2008, due to higher demand. This meant that negotiations with donor countries to replenish the current capital of the bank, usually done every three years, had to be brought forward to summer rather than towards the end of the year as scheduled.

"The [AfDB's] funds have already almost entirely been allocated," says Pierre Van Peteghem, treasurer of the AfDB Group. "Because of the financial crisis, the bank has front-loaded disbursements; therefore the resources have been depleted. That's why the negotiations have been brought forward. The last negotiations were concluded at the end of 2007, while this year's negotiations are meant to be concluded three or four months earlier in order for the AfDB to be able to continue its operations." Further, at its annual meeting in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, in May, the AfDB was due to deliberate on a suggested 200% capital increase from the current $33bn.

Pierre Van Peteghem, treasurer of the AfDB Group

IDB capital increase

Earlier this year, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) also agreed on a large capital increase. At its last annual meeting, in Cancun, Mexico, this March, the bank's capital went from $70bn to more than $170bn. This is the largest capital increase in the bank's history and will double its lending capacity to $12bn a year, says the IDB. The Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) also recently approved a significant capital increase of 150% to $5bn, to face growing demand from its region.

At the same meeting, the IDB agreed to increase its limit on loans to the private sector to 20% of the total equity of the bank. The previous 10% cap was so low that non-sovereign guaranteed operations never gained any traction and eventually fell off officials' radar. In the past, according to a senior official of a large multilateral bank, this meant that such loans were in reality as little as 4% of the bank's capital because nobody saw them as a viable tool.

EBRD's private focus

At the other end of the spectrum, a prime example of an institution working with the private sector is the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), whose preferred route of channelling development is through the private sector. On the capital markets side, the EBRD has done a phenomenal job in developing Russia's infrastructure, creating, among other initiatives, the first floating index rate in the country, MosPrime, which gave a reference rate to the local currency market.

In a region that has heavily relied on foreign currency and foreign exchange products to mitigate exposure risk, developing a local investor and savings base would help stabilise the economy and make it less vulnerable to external crisis.

"The [central European] region has relied excessively on foreign capital for its development," says Piroska Mohacsi Nagy, senior advisor to the EBRD's Office of the Chief Economist. "Also, the excessive use of foreign exchange, particularly in mortgages and consumer finance, to unhedged borrowers has to be addressed. Both have proved to be vulnerabilities in the crisis."

To tackle such issues, the EBRD has launched a new local currency and local capital markets project, which includes macroeconomic and regulatory considerations. This differs from its previous approach, where various pieces of regulation were discussed separately. Now any aspects relating to capital markets can be discussed at the same time. Greater collaboration with other multilateral agencies and private sector organisations will also be required to create a certain level of volume to kick-start these local markets.

"It is important that we do this with other partners," says Ms Mohacsi Nagy. "We're proud of our work. We're innovative but we're not very big, so we need to work with others. We've learned this from the crisis and we need to leverage on each other's [capabilities]. Together, the [international financing agencies] can make, in some markets, the market."

Local currency push

Other regional development banks have been ramping up their efforts in local currencies. In Latin America, besides the largest international issuer, IDB, smaller MDBs such as CABEI have been particularly active. In April this year CABEI raised 30bn colons ($57m) in its third issuance in Costa Rica's market. The notes, maturing in six months and linked to the local rate - Tasa Básica Pasiva - were 1.7 times oversubscribed. This is part of CABEI's new regional commercial paper programme in the Costa Rican capital markets. The first issuance took place in December 2009 with 6bn colons in similar notes. The issuance was well received then too, and was 1.5 times oversubscribed.

At the end of last year, the Central American bank was also the first international borrower to tap into the Dominican Republic capital markets with 740m in pesos bonds ($20m), maturing in five years with a 12% coupon.

Being the first international issuer means also getting familiar with the local requirements and bureaucracy. This can very often be off-putting, even for MDBs.

"[The Dominican Republic] is a market that has never had a foreigner before," says José Félix Magaña, CABEI's treasurer. "We used local documentation and the bond was settled in the country, [we] got approvals from regulators, the central bank, and all the other necessary ones. It's a very bureaucratic process. Now you can do it if you have the patience, but before it was impossible."

CAF's new territory

The Corporación Andina de Fomento (the Andean Development Corporation, or CAF) is equally proud of its capital markets presence. Beyond a series of local capital markets transactions, executive president Enrique Garcia points out that CAF has gone where no Latin American MDB has gone before. In May this year, it has placed notes in the exclusive Japanese retail market, Uridashi, traditionally reserved for highly rated issuers. The $74m, four-year maturity notes were placed by Daiwa Capital Markets.

There are many other cases of MDBs developing local capital markets through significant transactions. Or indeed milestones such as the Asian Development Bank's first ever renminbi-denominated bond issuance in the Chinese capital market, in 2005. The notes were for a total of Rmb1bn ($146m), 10-year maturity and a fixed coupon rate payable annually. Bank of China International was the lead manager.

Asia will no doubt continue to attract investors and development agencies' attention, including the ones with a more national focus, such as Germany's KfW, which intends to strengthen relationships with some existing Asian investors.

"If our activities are welcomed by the respective governments, we're prepared to consider issuing in those countries, also supporting the development of local capital markets," says Horst Seissinger, head of capital markets at KfW. "Our main target is to increase our investor base but at the same time we want to strengthen the relationship with our traditional investor base. For example, these are some of the central banks in Asia, which might appreciate our efforts to support the development of local capital markets."

Landmark: the Asian Development Bank issued its first-ever renminbi bond in the Chinese market in 2005

International vs local

Some are sceptical about the international DCM efforts the MDBs, given the higher risk and often limited history of the markets involved, while the general mood is to look for safe investments.

"At this time, when markets are very risk-sensitive and volatile, investors want to reduce their risk, not increase it," says Mr Brown from Citi.

When markets are highly volatile, investors seek liquidity, but bonds from smaller development banks typically offer very limited secondary market liquidity. As a result, investors demand compensation in the form of more generous pricing to buy illiquid bonds.

Smaller MDBs are aware of the importance of an issuance history in the international capital markets. They are also aware of the effects that unsuccessful bonds might have on their reputation and therefore their future ability to raise funds. This fear might hold back a few of them.

"When we issue a bond, we work in a minefield," says Igor Finogenov, chairman of the Eurasian Development Bank. "One wrong step and our reputation is damaged for years." Mr Finogenov says that he is still pondering on the bank's fundraising plans for this year.

Local welcome

If the international capital markets can be too big a step for some, issuances in local currencies might be welcomed by international investors, as experts believe that industrialised countries' currencies will weaken against emerging markets.

Mr Brown agrees that investors are attracted by issues in emerging markets currencies, which can combine very credit solid ratings with high yields. "European sovereign risk is investors' biggest concern in the current market and MDBs have been unaffected by contagion from Europe. In a world where the 10-year bund yields 2.8% and the 10-year treasury yields 3.5%, we've seen growing investor interest in AAA paper issued in high-coupon currencies including the South African rand, Mexican peso and Turkish lira," he says.

Emerging markets' currencies and capital markets are the new trends, and MDBs around the world are focusing on them. If prior to the crisis it might have looked as if MDBs were sailing along without much impetus, with decreasing loan portfolios in some cases, working under the unprecedented circumstances of the financial crisis seems to have reinvigorated spirits. CABEI's Mr Magaña says: "We're going to be more aggressive. We're going to work in integration-type projects in local capital markets. We want to help building infrastructure, interconnectivity between stock exchanges, custodians, paying agents. We can provide advice and financing, and we will bring on board some other multilaterals."