Foreign policy, fiscal pressures, financial reforms and far-reaching litigation are all provoking a flow of cases that threaten to overburden international banks doing business in the US. But the banks are fighting back. Philip Alexander reports.

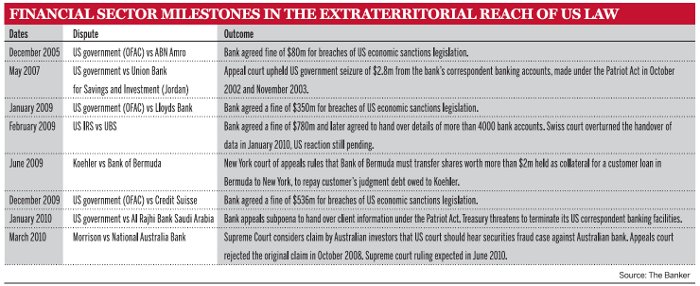

International banks have become rather too familiar with the inside of US courtrooms recently. They are still digesting the implications of US creditor Lee Koehler's success in June 2009, when a New York appeal court ruled that Bank of Bermuda should hand over to him shares held in Bermuda as collateral on a loan to one of its clients, Mr Koehler's debtor, David Dodwell.

In December 2009, Credit Suisse agreed on a $536m fine as part of a deferred prosecution deal with the US Office for Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) for breaching US sanctions against Iran, Sudan, Burma, Cuba and North Korea. One month later, Saudi Arabia's Al Rajhi Bank filed an appeal against the US Treasury's subpoena under the 2001 Patriot Act. The Treasury has accused one of the bank's clients of smuggling travellers' cheques and demanded that Al Rajhi hand over the relevant bank account details or face the termination of its correspondent banking services at US banks.

The US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is still deciding how to respond to the ruling by a Swiss court in January 2010, which struck down a deal involving UBS and the Swiss regulator. In August 2009, the Swiss had agreed to hand over to the IRS details of almost 4500 UBS accounts suspected of involvement in tax evasion by US residents. And on March 29, the US Supreme Court heard arguments in the case of Robert Morrison et al versus National Australia Bank (NAB). A ruling is expected in June 2010.

What all these cases have in common is the extraterritorial application of US law not only to foreign banks, but to assets or transactions involving those banks that occurred outside the US. The NAB case is the most extreme example, to the extent that lawyers and bankers have nicknamed it 'foreign-cubed'. The class action claimants are Australian, suing an Australian bank for allegedly misrepresenting price-sensitive information about its stock, which is listed in Australia.

Lawrence R Uhlick, chief executive officer of the Institute of International Bankers

Deterring investment

The justification given by the claimants for bringing the case in the US was that NAB's shares could be purchased in the US as American Depository Receipts, and because the alleged misrepresentation concerned the purchase valuation of Florida-based mortgage servicer HomeSide Lending in 1998. But lawyers and industry groups say the reasons for bringing this case in the US go beyond questions of law.

"We are too open to these global fishing expeditions to find a sympathetic court that could pay out huge damages," says Robin Conrad, executive vice-president of the National Chamber Litigation Center, the in-house public policy law firm for the US Chamber of Commerce in Washington, DC. Ms Conrad fears this risk will discourage foreign firms from investing in US subsidiaries.

A US appeals court had already refused to hear the NAB case in October 2008. But the court's decision was based on the specifics of the case - that the claimants had not proved the events in the US directly caused a loss to foreign investors. What industry groups want from the Supreme Court, which agreed in June 2009 to re-examine the case, is a so-called 'bright line' ruling that quashes the concept of foreign-cubed litigation altogether.

"There is no indication that Congress had this in mind in passing securities legislation. It also defies the laws of good sense," says Lawrence Uhlick, chief executive of the Institute of International Bankers (IIB) in New York. The IIB represents the interests of banks from 38 countries that have about $5000bn in assets in the US. He hopes that a Supreme Court ruling favourable to NAB would begin to "row back on extra-territoriality, for the sake of respecting the sovereignty of other jurisdictions, and for the sake of efficiency in the US legal system."

Both the US Chamber and the IIB have submitted amicus curae (friend of the court) briefs to the Supreme Court in support of NAB, along with an impressive international line-up including the US, UK and French governments, the New York Stock Exchange and a string of companies that have been the targets of other class action cases in the US. But a large number of Australian and European pension funds have also submitted briefs supporting the claimant, standing up for the right of investors to win redress if a company's management acts against their interests.

Legal logjam

Ms Conrad also refers to foreign-cubed litigation as a potential "court clogger", and this concern arises too in the case of Koehler versus Bank of Bermuda. While Morrison would make the US a forum for the world's securities litigation, Koehler would make New York the world's debt enforcement forum, because Mr Koehler himself lives in Pennsylvania and was not a New York resident - he brought the case in New York due to Bank of Bermuda's office there.

Joseph R Alexander is senior counsel at the Clearing House Association, which represents the 20 US and international payments clearing banks operating in the US, including Bank of Bermuda's parent HSBC. He compares the Koehler case to the way in which Federal courts expanded the concept of 'maritime attachment' in the early 2000s. Previously, this had allowed creditors to seize goods passing through New York ports, but it was extended to include fund transfers passing through New York intermediary accounts.

"It took a little time for the cases to bubble up, but for many months, the maritime attachment cases were one-third of the federal lawsuits filed in the Southern District of New York, which became a very big administrative burden on the banks until the court overturned its decision last October," says Mr Alexander.

The Koehler case, which was decided on the narrowest of margins, a four to three vote by the appeal court judges, also raises the possibility a bank might be caught in a conflict of laws. In the absence of an enforcement action in the foreign jurisdiction, its courts might forbid the transfer of assets held there to New York. The Clearing House Association raised this concern in an amicus brief to the court.

"One thing that is virtually certain is that the relationship between overseas banks and their clients overseas will not be governed by US law, which is a complication to put it mildly," says Bruce Clark of law firm Sullivan & Cromwell, which acted as counsel to the Clearing House Association for its amicus brief.

Mr Uhlick of the IIB says that future court cases could still overturn the principle set out by Koehler. But he and the Clearing House Association are also exploring the possibility of a New York legislative amendment, because the judgment was based on New York rather than Federal law. Banks with relatively small representation in the US could consider moving their offices out of New York to neighbouring New Jersey or elsewhere, which he regards as a "compelling reason" for the state legislature to change the law.

But the technicalities of Koehler may be low down on the agenda for local politicians, with the state budget in disarray. Marc Gottridge, litigation partner in the New York office of Lovells, says that in the meantime, a New York court judgment in February 2010 appeared to reinforce Koehler, by allowing a creditor to garnish assets in Delaware - not outside the US, but certainly outside New York.

Urs Roth, CEO of the Swiss Bankers Association

Taxing times

The fiscal difficulties of New York state reflect those of the US as a whole. With public anger already directed at the banking sector since the financial crisis, it has become a natural target for aggressive enforcement tactics by the IRS.

The Swiss courts delivered a knockback to the IRS over the UBS private client tax evasion dispute in January 2010. Urs Roth, CEO of the Swiss Bankers Association, says the case provided a clearer definition under Swiss banking secrecy laws of the threshold for banks to hand over client details - evidence of actual fraud, not just for a foreign government to check the accuracy of its citizens' tax returns.

"As a general rule, we believe that the circumstances under which one country gives effect to the laws of another should be governed by carefully negotiated and enforced treaty provisions and not ad-hoc initiatives on the part of law enforcement authorities or tax officials," says Mr Roth. His view was supported by the IIB, which filed an amicus brief in the case arguing that the mass summons of UBS private client account details contravened bilateral Swiss-US tax treaties.

But the US is not alone in seeking to encroach on Swiss banking secrecy law - the EU is co-operating closely in that campaign. "Perhaps there is an international impression that the Swiss will yield if enough pressure is applied and perhaps this impression is right. Prior to the statement by the Swiss court, there had been a growing tendency to change the rules retroactively," says Manuel Ammann, director of the Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance at St Gallen University.

With the reputation of banks in general - and UBS in particular - tarnished by the financial crisis, the Swiss population "is more willing to sacrifice the competitive advantage for Swiss banks, to avoid suffering the real or perceived disadvantages for keeping banking secrecy. The traditional offshore banking model probably has no future for Swiss banks and the largest have already moved their foreign operations onshore," says Mr Ammann.

Tax havens in hell

The US pressure is also changing the thinking of corporate taxpayers on their choice of jurisdiction for legal incorporation, says David Jervis, a corporate tax partner at law firm Eversheds in London. "There is a sense that Switzerland will be disproportionately affected by some of the Obama tax reforms, so we are seeing certain larger groups looking at how they can bring their operations back onshore, to Luxembourg or Ireland."

He adds that Bermuda and Caribbean jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands are also under pressure from the US, prompting insurance groups that are often domiciled in these countries to consider relocating. Yet low-tax regimes have so far shown little sign of co-ordinating a response to US extraterritorial legal pressure.

"One would think that co-operation among jurisdictions in the same boat would be natural, but it has not really worked. Switzerland has not been able to reach a common position with other jurisdictions that have similar banking secrecy laws such as Austria and there seem to be differences of approach even within each jurisdiction. The Austrian banks have been defending secrecy laws, while the country's finance ministry is apparently trying to buy Swiss bank account data on Austrian clients from the German government," says Mr Ammann.

Meanwhile, lurking in the background is an as-yet unformed suggestion that the US might also attempt to tax repo transactions between banks in US markets, which would presumably include deals involving foreign banks.

"We do not yet have enough details to make commercial decisions, but there has been a lot of criticism around the potential wide impact of this proposal. The US would effectively be taxing outside its own territory, which goes beyond what we have anywhere in other Western economies. There will be a lobbying process and maybe it will not turn out badly, but the general feeling is that things can only go in one direction at the moment - they are not getting better," says Mr Jervis.

Under sanctions

Some lawyers express similar sentiments regarding the application of US laws designed to support foreign policy and national security. Public pressure has mounted recently on companies operating in the US that have foreign subsidiaries with contracts in Iran, such as machinery manufacturer Caterpillar. This appears to be mirrored by the escalating scale of OFAC settlements with foreign banks.

"From what the US government has said, there are other banks not yet publicly named that will become subject to deferred prosecution agreements, although we don't have information about the number or size of such settlements. In terms of the political climate, you could make the argument that, as the government has taken the military option off the table, the sanctions regime is a more important tool and they are trying to get foreign companies not to do business in Iran," says Mr Gottridge of Lovells.

He adds that US banks face a number of problems in ensuring compliance with sanctions legislation, and seeking OFAC guidance of itself is no guarantee against enforcement actions later. Most OFAC actions are settled out of court, which means there is little case law for defining the limits of its powers and the reach of US sanctions.

"In the area of international payments, it can be very difficult for an international bank that provides dollar clearing services in the US to understand whether a transaction that originates in another bank in another country involves a party that is subject to US sanctions. We are concerned that recently announced enforcement cases may be extending the concept of liability for facilitating such transactions a bit too far," says Mr Roth of the Swiss Bankers Association.

The problem arises when banks send transactions to clear through dollar correspondent banking accounts in New York, but the clients on whose behalf the transactions were carried out have been subject to US sanctions. This is a particular risk in the case of so-called 'cover payments', where two banks carry out dollar transactions between each others' correspondent bank accounts in New York to cover dollar transfers between the two banks' clients in a different timezone.

Mr Alexander of the Clearing House Association says there has been greater clarity since last year, when a new payments transfer form was brought into use for cover payments, known as 202C, which requires the banks to detail the underlying client transfer to avoid clearing banks accidentally infringing US sanctions.

But sanctions against each targeted country are based on separate pieces of legislation with different drafting, while OFAC's own enthusiasm for enforcement also appears to vary - transactions in Iran are more likely to incur prosecution than, for example, those in Cuba. In addition, the EU has adopted legislation specifically seeking to block European companies from complying with the US Helms-Burton sanctions against Cuba.

Conflict of laws

Similarly, foreign banks facing action under the 2001 Patriot Act have often found themselves caught between the US and their home jurisdiction. The most far-reaching power of the Act, embodied in Section 319, allows the Treasury and Justice departments to seize sums from the correspondent banking accounts of foreign banks in New York equivalent to sums held in client accounts overseas that are suspected of involvement in terrorist financing or money laundering.

In 2002 and 2003, the US government seized a total of $2.8m from correspondent banking accounts belonging to the Jordanian Union Bank for Savings and Investments, held at the Bank of New York Mellon. This forfeit was due to Union Bank's alleged role in facilitating the laundering of proceeds from a Canadian telemarketing fraud carried out by two Palestinians. Union Bank was not able to recover the equivalent funds from the two suspects who had already withdrawn their money, but its appeal on the grounds that it was an innocent party was rejected in the US courts in May 2007.

In its own challenge to the Treasury's use of the Patriot Act, Al Rajhi Bank has also claimed a conflict of laws and is being supported by the Saudi authorities. The Saudi Arabian regulator has apparently informed the US that it would be illegal under Saudi law for Al Rajhi to hand over client details as requested, and that the request should have been made through diplomatic channels.

Stuart Stein, the head of the financial services and corporate governance groups at US law firm Hogan & Hartson, does not see much legal merit in Al Rajhi's claim that the Patriot Act subpoena itself is unconstitutional because the Treasury can order the withdrawal of correspondent banking services without a court order.

"What is left out of that concept is that Saudi Arabia is a party to the international convention on the suppression of financing terrorism, so it is required to co-operate in investigations in this area," says Mr Stein.

Looking beyond any individual disputes, he also questions the idea that foreign banks generally are still confused about the reach of the Patriot Act, almost a decade after it was introduced. "When people set up transactions through multiple accounts and entities and try to use legitimate institutions, but in countries where they know it will come under less scrutiny, that suggests that people understand very clearly and are trying to launder their money so that it can pass through a US account clean," says Mr Stein.

Unsurprisingly, lawyers involved in fighting money laundering and terrorist financing are also strong supporters of the Patriot Act. Charles A Intriago, the president of the International Association for Asset Recovery, was previously a Miami prosecutor specialising in financial crimes, and later a counsel to the US House of Representatives on the same issues.

Not all Patriot Act correspondent banking seizures are publicly disclosed, but he believes they number only in the low 20s, and most took place in the first few years after 2001. He says the US government has taken into account diplomatic relations with the home countries of foreign banks.

"In deference to that consideration, there were some very aggressive local prosecutors who were seizing foreign banks' accounts, but the Swiss government complained to the State Department, who complained to the Justice Department, who put out a notice to all its 93 US attorneys' offices around the country, that they will not enforce that provision of the Patriot Act without getting prior authorisation from the Justice Department in Washington," says Mr Intriago.

What's the alternative?

Mr Intriago says that the due diligence and disclosure required to ensure compliance with the Patriot Act and economic sanctions are a justified 'price of admission' to the vast US dollar correspondent banking network. But there are alternatives to that network, mostly located in financial centres that have access to a large pool of dollar reserves due to their countries' export earnings - Tokyo, Hong Kong and more recently Beijing and São Paulo.

Hong Kong's US dollar Clearing House Automated Transfer System (CHATS) was set up in 2000 with HSBC as its settlement bank and a network of 20 direct participants offering dollar correspondent accounts to their clients.

Michael Velez, the Asia-Pacific senior vice-president for global payments and cash management at HSBC, says 2.6 million transactions a year worth $2000bn are still only 0.6% of the volumes and values going through New York, but have trebled since 2001.

"The market is very liquid and we could handle much more business than we are currently doing; liquidity is not a limitation," says Mr Velez. In mid-2010, US dollar CHATS will switch from proprietary back-office software to the globally used SwiftNet system, which Mr Velez says will make it more cost-effective for smaller banks in Asia, the Middle East and Europe to migrate to CHATS.

Any change in the status of the US as a financial centre will be slow rather than dramatic. Michael Wiseman is the managing partner of Sullivan & Cromwell's financial institutions practice, who has been a counsel to ABN Amro and Lloyds in their OFAC cases, and to the Clearing House Association for its Koehler amicus brief. He says the US will remain a crucial market for the largest international banking players.

However, he sounds a note of warning. "In terms of strategy, people might not think about getting out of the US, but they would be thinking of how much to grow their US business as opposed to growing other businesses. Certainly the compliance and litigation costs - even if the defendant is successful - have got to be a factor that makes other markets look relatively attractive for growth," says Mr Wiseman.