Another fine mess? How penalties are calculated

Banks and commentators have often been left stumped by the processes used to calculate multi-billion-dollar fines levied by regulators in recent years. Danielle Myles looks at how penalties are determined by different authorities around the world.

Back in 2010, Goldman Sachs made headlines for paying the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) $550m to settle claims that it misled subprime mortgage investors. It was the biggest financial penalty in the SEC’s history, and its enforcement chief described it as a “stark lesson to Wall Street firms” that they would pay “a heavy price for violating fundamental principles of honest treatment and fair dealing”.

Fast-forward to today, and a fine of that size may fail to achieve the desired effect. While in the pre-crisis period financial regulators collected an aggregate of about $1bn annually, in the years since they have imposed double-digit billion-dollar fines on individual firms.

A new paradigm

This is reflected in banks’ provisioning. Data collected by regulatory risk intelligence firm Corlytics shows that legal and regulatory provisioning at the biggest US and European banks now often exceeds the funds they set aside to cover impaired assets. This has required a paradigm shift.

“For the past 200 years, all banks have understood credit risk, and market risk is now well modelled too. But they’ve only started to see billion-dollar fines since 2012,” says Corlytics CEO John Byrne. “Any time you have that big a loss event, no matter where it originates from, that is a huge risk.”

It is also a huge cost to the industry and economy. The Fixed Income, Currencies and Commodities Markets Standards Board found that 50% of UK banks’ net profits in 2015 were handed over in penalties for market abuse. According to Boston Consulting Group, the 50 biggest US and European banks paid $321bn in fines from 2009 to the end of 2016, a figure the Bank of England estimates could have supported $5000bn of lending.

Global principles

The enormity of today’s fines is widely cited, but what is less known is how they are calculated. There are myriad financial regulators around the world – some 300 in the US alone – and they each have their own methodology. But from analysing enforcement orders and judgments, Corlytics has identified 240-odd factors that can influence the size of a penalty, and three that invariably feature in any watchdog’s penalty calculation.

First is the seriousness of the financial harm and the amount the firm gained from the wrongdoing (either through higher revenues or costs avoided). Second is how long the behaviour continued and third is the firm’s misconduct track record. Another frequently occurring consideration is deterrence. “One of the objectives of the very large fines has been to get the banks’ – particularly the investment banks’ – attention to show this is a serious issue,” says Mr Byrne.

It means the final figure usually consists of two components: restitution or disgorgement, which removes the unlawfully gained profit and, where possible, returns it to the victims; and the punitive element, which is designed to discourage the firm and its peers from repeating the misconduct.

Regulator snapshots: US

Most major financial regulators have a published penalty regime, but they only go so far in helping understand the fines they levy. The SEC is a good example. Within its administrative proceedings remit, it calculates penalties according to a tiered tariff system. It assesses the wrongdoing – be it an ‘act’ or ‘omission’ – and imposes the fine ascribed to the appropriate tier. A technical breach would be tier one, which attracts the lowest penalty. Some misconduct might be a tier-two violation and intentional fraud would be tier three.

On top of this sliding scale, the SEC considers the overarching factors identified by Corlytics, such as profit obtained, harm to investors, and deterrence. Where things get tricky is interpreting how many incidents of wrongdoing the firm has performed. “One of the challenges is how you define an act or omission that violates or causes a violation of the securities laws, which can really impact the penalty amount,” says Conway Dodge, managing director at Promontory Financial Group. “A course of conduct, for instance, may be viewed as a single act or multiple acts.” For example, a single action that impacts 50 investors could be deemed one violation or 50.

Interpretation issues are not unique to the SEC. The US Department of Justice’s (DoJ's) starting point for calculating corporate crime fines is its sentencing guidelines, which are based on how much the alleged wrongdoer profited or the victims lost. “Even though the guidelines, on their face, set out a seemingly strict formula for calculating fines, the calculation of ‘profits’ and ‘losses’ is an extremely elastic exercise, which is why there is often significant room for disagreement, negotiation and advocacy on both sides," says Mythili Raman, a partner at law firm Covington & Burling and former head of the US DoJ's criminal division. For instance, it is difficult to assess how much profit a firm has generated from a $1m bribe paid four years ago.

Regulator snapshot: UK

The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is considered among the world’s most logical and disciplined regulators, in that it sticks to a five-step test in its public rulebooks. It calculates fines with reference to: the financial benefit obtained from the breach; the seriousness of the breach; any aggravating or mitigating circumstances; deterrence; and, if applicable, an up to 30% settlement discount.

“The starting point is to prevent firms from benefiting from a breach of the rules,” says Jenny Stainsby, a partner at law firm Herbert Smith Freehills. “There are subjective elements along the way but the FCA has to follow its five-stage process.”

The regime’s introduction in 2010 injected more transparency into the process, but there is still not absolute clarity in how figures are determined. For example, Ms Stainsby, who was formerly group regulatory head at Lloyds Banking Group, notes there is a lack of visibility in how co-operation (as a mitigating factor) is assessed and quantified.

Regulator snapshot: Asia-Pacific

Asia-Pacific’s most active enforcement agencies – Hong Kong’s Securities & Futures Commission (SFC) and the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) – have fairly simple and clear fining mechanisms.

The SFC is empowered to levy the higher of HK$10m ($1.28m) per breach or up to three times the profit gained or loss avoided. It directed The Banker to its disciplinary fining guidelines for the circumstances it considers when calculating a fine, which include the transgression’s effect on the market, and intent or recklessness. While these guidelines are publicly available, according to William Hallatt, a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills, “there is no public methodology for how the SFC calculates the fine”.

As in the US, identifying profit is a matter of interpretation. “[The SFC’s] view of that figure might be quite different to the firm’s view,” says Mr Hallatt. “Most firms would say the profit is the figure noted on its balance sheet after expenses have been deducted, but the SFC is often more simplistic and takes the fees earned on the transaction.” Furthermore, when the misconduct relates to just one of a firm’s many roles on a transaction, the regulator may incorporate all fees earned from each role.

The ASIC uses fine formulas set out in federal legislation that reference the national penalty units regime. The maximum fine for any breach is expressed as a number of penalty units (one unit currently equals A$210, or about $160). While this framework is relatively simple to navigate, the non-monetary aspect of penalties in Australia and Hong Kong – such as remediation and monitorship programmes – can be more troubling. “That is the tricky bit as you don’t know how much it will cost,” says consultant ComplianceAsia CEO Philippa Allen. “It’s quite subjective and I have yet to find a regulator that is very clear on what exactly their methodology is.”

Negotiating tactics

Most penalties, dubbed 'fines' by the media, are actually privately negotiated settlements. When a regulator reaches a point in their investigation where it believes it has a case, it usually puts its findings to the firm and offers an opportunity to settle. In principle, its opening offer should be in line with its fining formulas, but the reality can be different.

“When you are sitting in a room with them, it ends up being reduced to a regular commercial negotiation. That’s the unfortunate truth,” says Zach Brez, a partner at law firm Kirkland & Ellis in New York. “There is some number on which they think you won’t fight them, and that’s the number they often say is their bottom line.”

The potential discrepancy between a regulator’s opening offer and final settlement was laid bare in 2016 by Deutsche Bank’s penalty for allegedly mis-selling residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) pre-crisis. The DoJ’s original offer of $14bn, which was leaked to the press, was eventually whittled down to $7.2bn.

When facing US regulators in relation to an industry-wide scandal, it pays to get in first, when a bank will have maximum negotiating ability. The first few fines tend to set the benchmark on which other firms are assessed. “What we saw up until last year with the RMBS settlements was that the more banks delayed settling, the higher the fine tended to be,” says Fitch managing director Bridget Gandy, who adds: “Having said that, there has been a change of staff at the DoJ and they have not yet given any indication of how high they believe these amounts should be set.”

Global discrepancies

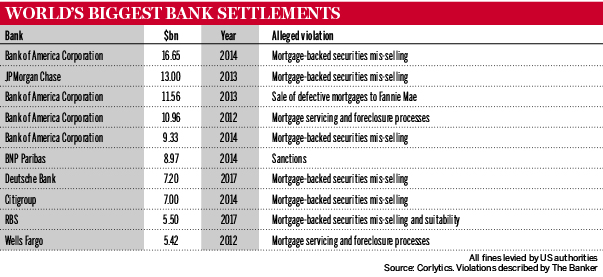

Indeed, there is speculation as to whether the new regulatory chiefs appointed by the pro-business US government will narrow the country’s lead as the world’s biggest finer. US regulators are responsible for the world’s 10 biggest settlements and MSCI data shows they collected 85% of banks’ regulatory settlements from 2008 to end-2016. They levied almost 97% of global fines for economic crimes (fraud, sanctions, tax evasion, bribery, misappropriation and anti-money laundering [AML]) from 2012 to mid-2017, according to Corlytics.

US authorities’ tendency to issue hefty fines is evidenced by cases they have pursued alongside foreign counterparts. Following the Libor rigging scandal that started in 2012, the UK Financial Services Authority (the FSA, the predecessor of the FCA) imposed a £59.5m ($78.5m) penalty on Barclays, £160m on UBS and £87.5m on RBS. These same banks paid US authorities $360m, $1.2bn and $475m, respectively. In 2017, Deutsche Bank settled allegations of AML control failings involving its Russian subsidiary by paying £163m to the FCA and $425m to the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS).

US federal regulators’ fining regimes do not explain this discrepancy, but many state watchdogs have less transparent methodologies. The NYDFS, for instance, collected $6.92bn in penalties for economic crime from 2012 to mid-2017, making it the world’s third biggest finer. It told The Banker it could not comment on its methodology for determining fines.

Same difference

Different enforcement philosophies also go some way in explaining the disparity. US regulators are focused on fines being more than a cost of doing business, and the country’s litigation culture is thought to have crept into its enforcement culture. The FCA, on the other hand, is more focused on restitution and influencing behaviour ex-ante rather than ex-poste.

“In the US, the standard is letter of the law and agencies tend to do after-the-fact regulation. They wait for something to blow up, and then they hit them hard to show they are holding people accountable,” says Matt Moscardi, head of financial sector research for MSCI ESG Research. “Elsewhere, regulators tend to be tight before the fact, and if you break the spirit of the law it’s a conversation and a slap on the wrist.”

There is evidence to suggest fines across western Europe will soon pick up. UK and EU authorities are dedicating more resources to sanction violations and AML (which account for a large chunk of global penalties), and a European law introduced in 2016 permits penalties of up to 10% of a firm’s annual turnover. “Fines related to AML breaches were capped to single-digit million euros in most European countries. But under the new AML directive there is the possibility to raise huge penalties,” says Norbert Gittfried, associate director at Boston Consulting Group.

Home ground advantage?

A common gripe among European bank bosses and policy-makers is that US regulators are harsher on foreign firms than local firms. Corlytics data shows that since 2012, 40% of US fines for economic crime have been imposed on 10 European banks. It is thought to be one reason why Barclays in December 2016 bucked the industry trend and snubbed the DoJ’s settlement offer regarding mortgage securities mis-selling allegation. Instead, it opted to battle the DoJ in court.

Barclays directed The Banker to the comment it made at the time, which states it “rejects the claims made in the complaint… [they] are disconnected from the facts”. In March 2017, Barclays CEO Jes Staley told CNBC the bank was “looking for a treatment that was commensurate with how the US banks were treated by the DoJ”.

One theory why US regulators have managed to extract large fines from foreign banks is because they leverage their powers regarding dollar clearing, an essential operation for any global bank, during negotiations. Faced with the prospect of losing this licence, a high settlement figure appears more palatable. But there are other explanations.

Regarding sanction violations, many non-US banks are very active in emerging markets throughout the Middle East and Asia. While their compliance processes may be adequate by home-country standards, they can still fall short of US requirements. “If they are processing dollar transactions on behalf of these clients, the US insists on a very high level of transaction surveillance due to sanctions,” says Mr Byrne. “[That] means a lot of European banks are being disproportionately done in the US for these fines.”

The money trail

Another frequently asked question, and one with a relatively simple answer, is what happens to settlement and fine proceeds? Penalties collected by the NYDFS go to the New York state fund and the FCA’s, DoJ’s, SEC’s and ASIC’s go to their respective government treasuries (although before 2012, the FSA used the cash to reduce the annual fees paid by the firms it regulated). Money collected as restitution or disgorgement goes into a relief fund to be returned to those harmed by the misconduct.

The way these figures are calculated – including by the more transparent regulators – is an evolving area of enforcement. “It can be more art than science,” says Mr Dodge. He says it is something that staff at the SEC (where he was once assistant director in the enforcement division) are constantly trying to be careful and thoughtful about. “But it’s very complicated to come to exactly what the right penalty should be. It’s not black and white.”

The FCA, the DoJ, the SEC and the CFTC did not respond to a request for comment on their fine methodologies.