The combined and cumulative effects of new regulations and a hostile market environment means banks are fighting to build both capital and liquidity. Many questions remain about banks' ability to do both, and the effects of doing either on economic growth.

In a quarterly earnings call in October, James Gorman, chief executive of Morgan Stanley, told investors and analysts that the investment bank is constantly reassessing “under what conditions we would act to shrink or change businesses” and added that: “We're not myopically focused on our size.”

The suggestion that the second largest US investment bank is thinking about shrinking provides stark evidence of the market and regulatory realities facing the banking industry. The combined and cumulative effects of Basel III, the EU's fourth Capital Requirements Directive and new liquidity regimes are having a staggering effect. In the coming months and years the global banking industry requires about €1100bn in additional equity capital, up to €1700bn in short-term liquidity, and about €2300bn in long-term funding.

Euro woes

In Europe, banks are being forced into immediate action in order to reach targets. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has set a June 2012 deadline for the continent's banks to reach 9% Tier 1 capital levels; following the latest round of stress-tests in early December, this means they will have to raise a total of €115bn in new equity capital.

Commerzbank, for example, which emerged with a shortfall of €5.3bn, has already said it will have to reign in international lending and speed up the sale of assets to achieve the EBA target, and is in the midst of a hybrid buyback in order to boost Tier 1 capital.

In November 2011, Banco Santander, Spain's largest lender, sold its Colombian arm to CorpBanca of Chile for $1.2bn, which it hopes will create gains of €615m, as part of a drive to raise capital. It follows an earlier announcement that Santander is also selling 7.8% of its Chilean business, in a deal expected to raise about $1bn, and plans to sell up to 8% of its prized Brazilian unit.

Robert Charnley, head of regulatory reporting and new products at Goldman Sachs, says it is unsurprising that banks are shedding assets and carrying out liability management plans. “Clearly the amount of equity across the system isn’t enough to meet Basel III requirements when they fully kick in. But given the environment, banks are deleveraging because raising new equity is very difficult right now,” he says. “The regulators have laid out a timeline to meet new requirements, but the markets are demanding that [banks] reach those targets as soon as possible.”

Capital question

Once Basel III is fully implemented in 2019, the common equity requirement rises to as much as 12% for the largest institutions. That comprises a 4.5% basic equity requirement, a 2.5% capital conservation buffer, another 2.5% in a counter-cyclical buffer, and up to 2.5% on top of that for globally systemically important banks.

The obvious step towards the new goals is to issue equity, and banks such as Bankia, Aareal Bank and UBI Banca did so last year. Others, such as UniCredit, are hoping to do so soon. However, this is an unpalatable choice when bank shares are trading at a fraction of their book value. According to data from New York University, the world's 10 largest banks, for example, have lost about $250bn of market capitalisation since March 30, 2011. At the beginning of October last year, Bank of America-Merrill Lynch (BAML) was changing hands at 29% of its book value.

As a result, liability management and deleveraging exercises are well under way as banks push for core capital gains. In the third quarter of 2011 alone, BAML reduced its balance sheet by $42bn and its risk-weighted assets by $33bn in a bid to increase its Tier 1 capital ratio. In an interview with The Banker in December 2011, Christian Meissner, co-global head of corporate and investment banking at BAML, admitted regulations were driving the scale and shape of the business.

“The regulatory environment is impacting everything we do,” he said. “You can see the impact of Basel III in terms of our risk-weighted assets, the amount of capital we need to hold, the kinds of business we do, the amount of lending we do and the kinds of structures we commit to. It's fundamental.”

Investor appetite?

If banks do want to issue new equity, it is anyway unclear whether enough investor appetite exists. At a fundamental level, many investors are questioning profitability at this point in the cycle as well as the core earnings power of the industry going forward.

“Of course we're looking for a well-run bank offering a good return and getting some growth, but we also invest where the cycle is favourable, and we are at a point where earnings are deteriorating,” says Robert Mumby, lead manager of Jupiter's Global Financials and International Financials funds. “We have very few holdings in Europe at the moment because European banks are too risky.”

An important part of the capital question is the issue of bail-in bonds, which aim to shift the burden to insolvent banks' capital suppliers, including senior creditors. Can bail-in be made to work? There are plenty of issues to be overcome, not least getting the conversion trigger right and a workable cross-border insolvency framework in place. “There are still a lot of other questions to be answered, such as grandfathering, the hierarchy of claims, exclusions and depositor preference,” says one credit investor. “So far we are sticking to secured alternatives.”

However, many bankers are relatively optimistic. Wilson Ervin, former chief risk officer at Credit Suisse and now a special advisor to CEO Brady Dougan, says investors are increasingly accepting of the idea. "Investors buy the bonds of multinational companies and their debt is, in effect, bail-inable," he says. "Yes, banks are relatively complex organisations, but the conceptual argument is the same. I think investors understand that bail-in is the most attractive private sector alternative, much better than liquidation or a disorderly collapse."

Utility model limitations

But at the core of the debate is whether banks can remunerate capital at levels attractive to investors. Clearly, a major premise of incoming regulation is the notion that if banks are made safer, investors will be prepared to accept much lower returns on equity (ROE). In this new world, banks will have a utility-style profile in which earnings are stable rather than stellar; but can a utility model be applied to banking?

Patricia Jackson, head of prudential regulation and risk at Ernst & Young, thinks not. She argues that institutional investors accept utilities' lower ROEs because they are predictable and stable: their assets are transparent, their charging structure is clear and they have a virtual monopoly, so investors are able to value utilities accordingly.

“Banks do not and cannot fit this profile,” says Ms Jackson. “How much risk is there in a monopoly company – can a water company fail? Banking is a wholly different business model and operating environment. It has cyclicality where utilities do not; because of unique competitive issues, it has information asymmetries that cannot be entirely eliminated, even with the greater disclosure that new regulations will bring in.”

Mr Mumby agrees that it is impossible to compare them because, unlike utilities, banks are both cyclical and geared, so an investor's risk rises quickly as the macroeconomic environment deteriorates. “To think that banks can deliver the same return as an electricity or water company and that investors will accept it is a bit optimistic. Bank risk is just too great. As we've seen, if you invest in a bank and it goes wrong the dilution is enormous,” says Mr Mumby.

“If banks have twice the capital, it doesn't mean they are half as risky,” he adds. “Even if banks had twice as much capital as they have currently, an investor will still lose money if Europe blows up; a bank is still geared and not immune from going bust. The problem with banks is not so much the levels of capital, it's the riskiness of their assets.”

Key to persuading investors that bank equity is safer, is improving the quality of disclosure so that investors can rely on the published capital ratios to judge the relative strength or attractiveness of different banks. Goldman's Mr Charnley believes that in the long term, industry stress-tests – which apply the same standards across different parts of the system – will be the best way forward.

“If the regulators get that right, and are able to give confidence that the way they stress-test banks and the publication of the results is robust, that's probably the best way investors can judge the relative health of different banks,” he says.

Liquidity requirements

The other pinch point for banks is much more stringent liquidity requirements. The key elements under Basel III are: the liquidity coverage ratio, designed to ensure banks can survive a month of acute liquidity stress; the net stable funding ratio, intended to encourage the funding of illiquid assets by stable deposits; and the principles of sound liquidity risk management and supervision, requiring banks to enhance their internal controls, supervisory reporting and public disclosure of liquidity risks.

The resulting challenges for the industry are three-fold: composition of the liquidity pool, cost and implementation. “It costs a lot and it takes time,” says Ms Jackson. “To have the right information available on a consolidated basis, intraday and every day, requires a huge amount of investment into technology, processes and governance. It is not just a question of having the information; it is also about having people who understand it and will make the right decisions based on it.”

In some ways, the supply constraints – such as the availability of deposits, medium-term funding and high-quality assets – make meeting liquidity requirements a bigger challenge than raising capital. Thus far, a high proportion of the pool has to be in government bonds, but increasingly the industry is calling for a broader range of assets to be eligible.

Deciding what can be used is a thorny issue, says Mr Ervin. “Defining government bonds as risk-free has obviously now been called into question and there aren't enough to go around anyway, so we will need to broaden what is eligible. Whether that's expanding the universe through greater use of covered bonds or certain other AAA type assets, subject to some tough tests or a significant haircut, that's unclear,” he says.

Many bankers say it is worth considering high quality equities. "I was surprised at how liquid high-quality equities remained during the crisis – in some respects they ended up being less risky and easier to borrow against than many other assets, even some government bonds," says Mr Ervin. "If you looked at trading in Greek bonds now versus the S&P 500, it's no surprise that the latter is a lot more liquid.".

But this is an uncomfortable notion for regulators, who see equities at the opposite end of the risk spectrum from government bonds. Similarly, with securitisation still a dirty word, the potential for this technology to fulfil multiple objectives has been largely ignored so far, says Ms Jackson.

“A very simple, high-quality securitisation vehicle – one with almost no complexity in the vehicle, and complete transparency over the loans and risks in the pools – could provide a useful tool,” she says. “It would provide another high-quality asset to go into the liquidity buffers, at the same time as funding the balance sheet and helping with deleveraging by taking assets off the books.”

Painful process

There is no getting away from it, however; banks will have to go through the pain of what Ms Jackson calls the “big adjustment”. She divides the journey that banks have to take into two halves. The first is the painful part: returns on equity will have to go down and margins will have to go up; costs – including compensation – will have to go down; leverage will have to go down; business models will have to be reshaped.

“The question banks should be asking themselves is what can we do to reduce the pain of transition?” says Ms Jackson. There are several straightforward steps that banks can take, she adds, some of which will anyway be part of resolution and recovery planning. For example, they can streamline legal entity structures to make regulation, capital, liquidity and tax changes less painful.

Additionally, while banks cannot reduce the conservatism in their capital calculations, they can look at where data is pushing it up. For example, derivatives houses likely have netting agreements waiting to be agreed in the legal department. Until they are finalised, gross exposures go into the capital calcuation. Similarly, banks will have missing data in some of the credit risk modelling calculations, which means that they are having to put in added buffers. Improve the data and banks can reduce capital requirements.

Equally, banks should look at areas of the business in which they are holding assets where the risk-weighted assets are very high. In credit card books, for example, there is likely room to close down dormant, unused cards or to cut undrawn lines against which they have to put up capital.

Strategy optimisation

In the second half of the journey to adjustment, Ms Jackson says banks will have to carry out a complex three-way optimisation of the business across capital, liquidity and leverage. “It's about completely rethinking the business and asking difficult questions about what businesses can be profitable in the new environment.”

Ms Jackson says that this already complex process will be further complicated by the number of moving parts and the competitive landscape. “Part of the strategy will be deleveraging: deciding what businesses they sell or exit, and what they keep. But given that everybody is changing their strategy at the same time, banks must think carefully about the sensitivity of their strategy to that of other banks,” she says.

To make the transition successfully, banks will need to update their finance models, Ms Jackson adds. “Banks have fairly simplistic economic capital and finance models to set their strategy; they’re bolting together multiple spreadsheets that look at bits of the business individually. This is not enough to address the complex three-way optimisation that they need to do. They need a next-generation of tools.”

Economic impact

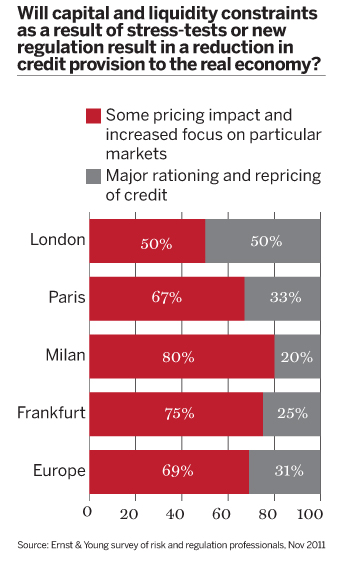

Policy-makers have thus far seemed convinced that the cumulative effect of multiple regulatory changes will have a minimal effect on the economy. Others are not so sure. Ms Jackson says regulators need to keep a careful eye on the outcome of their decisions. "The adjustment period is going to be much tougher than the authorities envisage. If it becomes clear that parameters or timelines need to be adjusted, or other measures have to be taken to avoid unintended consequences, then regulators and policy-makers need to be vigilant and be prepared to do that,” she says.

Mr Charnley is optimistic that there is a growing sense that regulators are willing to listen to reasons for bank behaviour that they did not envisage or that might be harmful to the system or to economic recovery. “They're certainly prepared to listen very constructively if banks can bring concrete examples of stresses in the system. For example, is the interbank market drying up a response to the eurozone crisis or a response to new regulations or a bit of both? My sense is that regulators are interested to understand why that is and what may be done to alleviate that. Because it's clearly not something that they want to see.”