Few will deny that bank boards were as culpable as their senior management in failing to spot the dangerous levels of risk building within the banks in the lead-up to the financial crisis. There is clear recognition that things need to change. But changing risk structures, and more importantly, risk cultures, is easier said than done.

As regulators insist that banks change their ways and strengthen their defences against another ruinous crisis, some bankers complain that their demands are unnecessarily onerous. There is, however, one particular area where few dispute the pressing need for reform – in risk governance. But willingness to comply does not change the fact that overhauling risk structures and cultures is easier said than done.

In the buoyant lead-up to the crisis, many banks grievously underestimated the levels of risk to which they were exposed. Some failed to aggregate concentrations of subprime mortgage risk across many different business areas and, as the boom progressed, value-at-risk models based on insufficiently long data histories lulled many into a false sense of security. Even Basel II internal ratings-based models proved misleading if they used a point-in-time rather than through-the-cycle methodology. As banks rushed to sell good assets, liquidity problems emerged in unexpected places.

Major failure

This failure by banks to measure and to understand the true extent of the risks they were facing was pinpointed as a major cause of market turbulence in 2007 and 2008, not least by the President’s Working Group on Financial Regulation and the Senior Supervisors Group (SSG) of major market regulators. Recommendations and statements of best practice were not slow to emerge from various bodies, including global industry association the Institute of International Finance (IIF), as well as the Counterparty Risk Management Group, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the SSG itself.

The IIF articulated a set of principles designed to promote a consistent and effective risk culture, run from the top. Risk management, it said, is the responsibility of senior management, particularly the CEO, and the board has an essential oversight role. Boards should set, and regularly review, goals for risk appetite and strategy, and monitor performance over time. Risk management should be the direct responsibility of a chief risk officer, with enough seniority and independence to do the job properly. It should not be overdependent on particular models or a single methodology, and models should not be a substitute for 'thinking'. It should avoid the silo approach and aggregate risk across the firm, while making sure governance structures are implemented at an operational level. Finally, banks should stress-test more consistently and comprehensively, taking into account exposures and aggregations that may have been previously overlooked. Stress-testing results should have a meaningful impact on business decisions.

Banks, particularly those that had been hardest hit, did not need too much urging. Today, a majority of bank boards have realised that they can no longer merely rubber-stamp the risk appetite fed up to them by management but must take control of the process. In an Ernst & Young survey of IIF-inspired changes in risk management practices, published in 2011, 83% of respondent banks reported an increase in risk oversight by the board, 87% of boards were spending more time on risk management and 86% had established a separate board risk committee.

“The idea that bank boards must understand and be involved in setting risk appetite is now fairly well accepted,” says Barbara Ridpath, chief executive of the International Centre for Financial Regulation. “They are not all doing it well, but it’s at the front of most of their minds. Permeating it down to the level of operations, to traders and managers, is a different matter, but at senior and strategic levels they get it – and they understand they will be questioned on it by investors.”

The hard part

Accepting board responsibility is clearly the easy bit. Developing a risk appetite framework is less so, and banks are at different stages along this particular road. There is near unanimous agreement that one size does not fit all, even if the overriding principles are the same: to establish a sensible framework and get everyone in the organisation to buy in to it.

The frameworks themselves take different forms. National Australia Bank, for example, has formulated a 'risk appetite statement' with three elements: a risk 'budget', the economic capital limit within which the bank must operate; a risk 'posture', a qualitative expression of capacity and willingness to take risk in each line of business, ranging from 'conservative' through 'neutral' to 'expansionary'; and risk 'settings', that prescribe key operational limits.

Risk appetite is not the same as strategy, but the two are closely linked. Stilpon Nestor, managing director of corporate governance consultants Nestor Advisors, sees setting risk appetite as a top-down cascade which starts with the determination of absolute risk capacity (the limit beyond which the firm’s survival is threatened) and which should be coordinated with the setting of long-term strategic objectives.

Recovery and resolution planning, determining which businesses would be jettisoned to keep the firm afloat, can shed useful light on the risk debate, Mr Nestor believes. He is insistent, however, that this debate should not be ghettoised inside the risk committee. “If risk appetite is a twin sister to strategy, it follows that the whole board should have the responsibility for its development, discussion and approval,” he says.

Too many metrics?

Choosing the right metrics can be a challenge, not so much for credit or even (more difficult, given hedging exposures) market risk, but for less quantifiable areas such as operational and reputational risk.

“You don’t want to have too many metrics, but you need ones that you can allocate to business units and make them accountable to,” says Patricia Jackson, head of prudential regulation and risk at Ernst & Young. Banks must bite the bullet, she says, and accept that they are actually thinking about “appetite for loss”. Given their strategy, how much loss are they prepared to absorb?

Morten Friis, chief risk officer at Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), agrees that loss is a good place to start the discussion, though it is unlikely to feature in the chosen metrics outside of operational risk. Those metrics, he maintains, need to be forward-looking.

“The metrics must speak to future risk,” Mr Friis says, insisting that they should not focus on asset quality. “Levels of impaired loans or provisions for credit losses reflect decisions made one-and-a-half to two years ago. They are less able to speak to the profile of losses in the coming quarter.”

Levels of concentration in the business are a better expression of risk appetite, since all concentrations give rise to a potential for loss, and here stress testing provides a forward-looking view. “The whole area of stress-testing helps you to understand how the business would perform under a range of different stresses, and where concentrations could hurt you,” says Mr Friis. “Then you can make a decision on whether the return is worth the risk you are taking.”

RBC, he notes, runs more than 30 stress scenarios every night so that it can understand the vulnerability of the business and its portfolios to different combinations of stress and tail events. “Your tolerance for stress-related losses needs to be calibrated,” he says.

Tech importance

Data collection and analysis is vital to the process and, as SSG has pointed out, many banks’ IT infrastructure is inadequate for the accurate monitoring and aggregation of risk exposures across the entire business. SSG admits that this problem has been a long time in the making, and will take a long time to put right. But, in the same context, it has called on firms to “re-examine the priority they have traditionally given to revenue-generating businesses over reporting and control functions”.

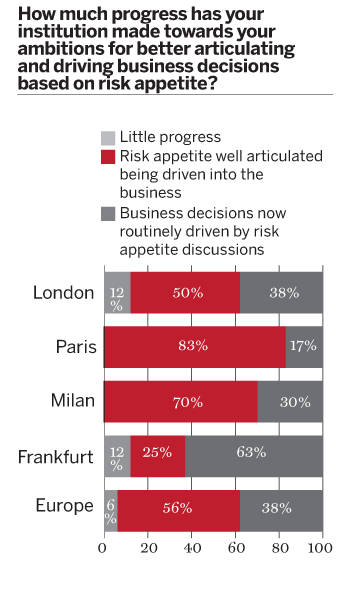

The framework needs sufficient clarity to allow it to be fed down the organisation, to where the day-to-day risk management decisions are made. This is the hardest part of all. Execution is a major issue and, for most, a daunting one. While 96% of banks in the Ernst & Young survey said they had increased their focus on risk appetite, only 25% claimed to have linked it to business decisions.

The ultimate destination is a pervasive risk culture in which any significant decision at any level of the bank, from the boardroom down, automatically takes into account the impact on the firm’s risk profile. RBC carries out a periodic portfolio review of its three dozen or so lines of business. That now includes a discipline of measuring each against the bank’s risk profile and appetite, to guide strategic decisions on whether to stay in the business or to get out. “In most institutions, that’s still pie in the sky,” says Mr Nestor. “In the best ones, it’s a work in progress.”

In the worst ones, he says, information on risk is very fragmented and the central risk management function is very weak. “It’s usually a combination of not enough commitment and a persistent legacy in the institution,” says Mr Nestor. “Of course, if you have enough commitment, you change the legacy.”

Acquiring a risk culture is a dynamic rather than a finite task – the board cannot simply decide it is time to get one and then move on, job done. “There is no silver bullet here,” says RBC’s Mr Friis. “This is an important tool, but it’s not static and needs continually to evolve. And within two to five years it should evolve into something that is appropriate to both the institution and the markets.”