The new regulations designed to tame the world's banks and mend the post-crisis financial system are panning out with unintended consequences which threaten to hit the private sector where it hurts most. Michelle Price reports.

In cracking down on the banking sector, global regulators are in serious danger of hitting private sector companies by mistake.

A slew of impending regulatory measures which aim to make banks and markets more robust and transparent are likely to have the unintended consequence of hampering corporates, slowing exports and stymieing growth.

Worse still, in some cases, regulations designed to reduce systemic risk are merely pushing it out of the banking sector and on to companies, leading some lobbyists to warn that the next crisis could arise from the corporate sector.

Both the US and European regulation of derivatives, which include reforms designed to stamp out speculation, threaten to hit the one set of institutions- non-financial corporates and industrial companies - which use financial instruments not for speculative purposes but to hedge cashflow exposures caused by foreign exchange movements and volatile commodity prices.

In some cases, the amount of cash collateral a multinational corporate would require to centrally clear complex, long-term derivative contracts - a key feature of both the US Dodd-Frank Act passed in July and the proposed European Market Infrastructure Legislation - would equal if not surpass its capitalisation, warns the European Association of Corporate Treasurers (EACT).

To satisfy these requirements, many corporates would have to turn to their bank for additional funding facilities to cover the gap and in some cases, "they would just run out of cash," says one treasurer. Furthermore, higher counterparty-credit risk capital charges, combined with restrictions on proprietary trading, will reduce liquidity and increase the cost of hedging for corporate end users.

Regulators are attempting to assuage lobbyist fears by proposing exemptions for derivatives used to hedge tangible commercial risk, but confusion and uncertainty surrounds the definition of commercial hedges and the proposed exemption thresholds. A resolution could take months if not a year.

And these are not the only regulations which threaten to target corporate activity. The unintended consequences of new Basel III provisions, published in December 2009, are even more perverse.

By clamping down on off-balance-sheet finance, the new Basel III requirements will penalise trade finance instruments, such as letters of credit, with far reaching and damaging outcomes for global trade - the very engine of growth needed to resuscitate moribund Western economies. Basel III's liquidity cover ratio, meanwhile, could sharply increase the cost of short-term corporate funding.

And the worst affected companies will be small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) - just the sector that governments are looking to for expansion and job creation. "The SMEs are really in deep trouble," says deputy managing director at the Institute of International Finance (IIF) Hung Tran.

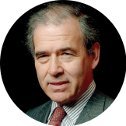

Private sector pain: EACT chairman Richard Raeburn says a requirement to clear derivatives centrally will put pressure on companies' liquidity

Derivative danger

Dire warnings regarding the cost of financial regulation to the corporate community have been most loudly voiced within the over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives industry which, widely blamed by market watchers and regulators alike for exacerbating the financial crisis, has been caught in the regulatory headlights.

A key feature of both the US Dodd-Frank Act passed into law in July, and the European Market Infrastructure Legislation (EMIL) proposed by the European Commission, is an aggressive attempt to improve the transparency and robustness of the OTC derivatives market by mandating that the vast majority of OTC derivative contracts be collateralised or cleared through a central clearing counterparty (CCP). Although the finer details of both pieces of regulation will not be determined for some months to come, it is becoming increasingly evident that non-financial corporate users of derivatives are unlikely to escape either piece of legislation unscathed since corporate derivative trades are generally transacted over the counter (OTC) and, for the most part, are not collateralised.

But the suggestion that industrial companies may be subjected to the same collateralisation and clearing requirements demanded of financial institutions is a deeply alarming prospect for corporate treasurers, who protest that the associated liquidity risk of any such move could prove financially devastating.

Any industrial company forced to clear its derivative trades through a CCP would be required to stump up a large chunk of collateral in the form of initial margin amounting to about 2% to 3% of the nominal value of the derivative. Of greater concern to treasurers, however, is the daily variation margin required to cover negative mark-to-market changes in the value of the contract.

Unlike banks, most companies simply do not have the assets or cash reserves readily available to meet the liquidity requirements that collateralisation demands. "There will be considerable liquidity risk created for companies if their transactions fall under the scope of the new regulation and they are forced to centrally clear," says Richard Raeburn, chairman of EACT. According to lobby groups such as EACT, the proposed derivatives reforms threaten to transform the counterparty credit risk borne by the bank into a liquidity risk borne by the end corporate user.

The problem, say bankers and treasurers, is that the mark-to-market basis on which margin requirements are calculated is a forward accounting concept that jars with the way the majority of corporates use derivatives - to hedge commercial risks and stabilise the value of future cash flows. For example, a manufacturing company may use a derivative to lock-in the foreign currency value of future invoices that are not payable for six months. "But under the collateral agreement for that derivative the present value of those cashflows has to be collateralised on day one," explains Russell Schofield-Bezer, managing director, European head of corporate debt capital markets and derivative sales at HSBC Investment Bank. "How can they fund from current operational cashflows the collateral against a mark-to-market position when the actual cash inflow they are hedging occurs in the future?"

In some instances, such as a cross-currency swap, the hedge may have a maturity of several years. Collateralising such trades is simply unfeasible, say treasurers. "If corporates had to post collateral, that wouldn't be a good situation at all," says a corporate treasurer at a global airline. "Corporates use those products to hedge exposures which could go up to 10 years: if they had to post in one single period the amount of cash to cover the market-to-market movement on a 10-year hedge, corporates would just run out of cash," he says.

To complicate matters, the requirement to collateralise would force many industrial companies to draw on their bank credit lines. "This doesn't remove the counterparty risk, it just creates a liquidity risk, which is met by drawing down on an overdraft," says Mr Schofield-Bezer. "That risk is just transferred from the trading book to the banking book, and that's a book that is not familiar with managing the risks associated with derivatives," he adds.

Russell Schofield-Bezer, managing director, European head of corporate debt capital markets and derivative sales at HSBC Investment Bank

A matter of speculation

The Dodd-Frank Act and the EMIL draft directive have sparked outrage among the world's largest industrial companies, 160 of which put their name to an EACT letter of protest sent to the European Commission in January. According to the association, the amount of cash that would be required by some corporates to fulfil the draft EMIL directive could reach 100% or more of their market capitalisation. Prior to the passing of the Dodd-Frank Act, US corporate lobbyists estimated that its provisions could require non-financial users of derivatives to produce up to $1000bn of collateral in total.

Bowing to the mounting pressure, the architects of the Dodd-Frank Act included a last-minute exemption for what it defines as "commercial end-users" of derivatives. In Europe, meanwhile, September's finalisation of the EMIL takes a similar view, noting that derivative contracts should be exempt if "they have been entered into to cover the risks arising from objectively measurable commercial activity".

But corporates cannot breathe a sigh of relief just yet.

For one thing, neither the US nor Europe have defined what exactly constitutes a risk-mitigating commercial hedge or how exactly to identify it. In both jurisdictions this critical element of the legislation is still up for grabs and will prove equally as controversial to pin down as the legislation itself.

For although lobby groups have found it in their interests to claim otherwise, there are some non-financial entities which do enter into the 'speculative' or non-commercial use of derivatives trades so loathed by the regulators. Big commodities players such as producers or so-called commodities 'suppliers', such as Glencore, are frequently big speculative players in the commodities derivatives market. And it is not just the commodities houses. Take Porsche, for example: in 2007 analysts accused the luxury car manufacturer of behaving like a hedge fund when its first-half results for 2007 revealed it had made three times as much profit on derivative deals as it did by making cars.

One of the key outstanding questions therefore is how a regulator, or indeed a corporate, is to identify a non-financial derivative deal that is not entered into in order to hedge commercial risk.

There are some suggestions on the table. The Economic and Financial Affairs Committee of the European Parliament has published a report that calls for transactions that meet the requirements for hedge accounting to be automatically exempt. Hedge accounting aims to mitigate profit and loss volatility by allowing the exposure and the reciprocal hedge to be booked as one item, meaning large swings in the mark-to-market value of either side of the trade are effectively balanced out. "If you qualify for hedge accounting then that may be a mechanism by which you can identify commercial hedging," explains Mr Schofield-Bezer, and EACT supports this suggestion.

However, many companies are not always able to achieve hedge accounting for commercial hedges, adds Mr Schofield-Bezer. Take an airline for example.

To hedge its exposure to jet fuel, an airline may purchase a more cost-efficient proxy in the form of a highly liquid crude oil derivative. But, since the price of crude oil and jet fuel do not necessarily move in sync, these types of hedges will not always satisfy the requirement for hedge accounting.

The European Commission also proposes quantitative thresholds by which a transaction should also be tested in order to determine whether or not it must be cleared. Again, these thresholds have not been detailed and could linger unresolved for up to a year. Furthermore, after the corporate has breached this threshold all its transactions thereafter will have to be cleared.

Little more clarity surrounds the US's Dodd-Frank Act, which is widely regarded by regulation lawyers to be so arcane and ambiguous that some bankers believe the exemption rule may yet require further revision. Moreover, the actual detail is undetermined and it will fall to the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission to practically interpret the act. As a result, lobby groups such as EACT are concerned that the practical implementation of the legislation may ultimately prove more stringent.

And although Dodd-Frank provides for a "commercial end-user" exemption, the act also stipulates that any entity, including corporate end-users, that qualify as a "major swap participant" will be directly regulated and thus subject to the attendant regulatory burdens as a dealer. According to an extensive memo on this issue by international law firm Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP, however, it remains "unclear whether the number of end-users required to register as a major swap participant... will be 10,000 or 10: it is left to the regulators."

Anthony Belchambers, CEO of the London-based Futures and Options Association, believes the largest corporate users of derivatives may yet be ensnared by this ambiguous part of the legislation. "The US line appears to be that if you are a significant end-user, even though you are not operating any licensable financial business for someone else, you may be directly regulated," he says.

Anthony Belchambers, CEO of the London-based Futures and Options Association

The counterparty catch

Even if the corporate community secures a generous and far-reaching exemption under the fully fleshed incarnation of both the Dodd-Frank Act and the EMIL, the new Basel III provisions outlined in December 2009 may deal a further blow through its proposal to increase the capital charge levied against counterparty credit risk.

In a bid to mitigate the explosion of poorly capitalised counterparty credit risk that expanded in banks' trading books prior to the crisis, the new Basel proposals will require banks to hold substantially higher capital against counterparty credit risk on derivatives, repos and securities financing activities.

According to Standard & Poor's, this additional capital burden, which it said in April could result in charges far higher than the counterparty risk losses endured during the crisis, is likely to heavily penalise the derivatives business. Although Basel's stance on the counterparty risk charge softened somewhat in July, many dealers still believe it will result in a dramatically larger capital burden and will in turn drive up the costs of trading derivatives.

As such, the new provision may render the derivatives clearing exemption irrelevant: a corporate entering into an OTC derivative transaction might dodge the margin requirements associated with clearing through a CCP but it is still likely to be hit by the associated cost of the Basel III counterparty capital charge which will naturally be higher for riskier non-collateralised trades - the very type of transaction corporates hope to preserve. "Even if we get a favourable outcome on the derivatives regulation there has from the beginning been a threat that would be undone by the new Basel III rules," says Mr Raeburn.

This would be a perverse and frustrating result for corporates to whom the increased counterparty credit risk charge "looks irritatingly like an indirect tax on commerce designed to compensate for a crisis to which they were not party", says one banker. Of course, the higher counterparty credit risk capital charge is designed to make centralised, transparent market infrastructures such as exchanges and CCPs more attractive to dealers. But Basel does not regard the latter as risk-free either. The July 29 Basel III annex also proposes subjecting banks' mark-to-market and collateral exposures to a central ounterparty to a "modest" risk weight which is likely to be about 3%.

Although this risk weight may have no direct bearing on the cost of corporate hedges, as with the regulatory drive towards centralised clearing and higher collateralisation, it is one of several additional incremental costs that will serve to inflate the overall industry cost-base. "Since dealers will be operating in a business environment of higher costs and thinner margins," says Mr Belchambers, "they have little choice but to pass those costs on to the unregulated counterparty or end-users. This means that risk management costs are likely to get significantly higher."

In addition to the broader clearing and collateralisation costs and the Basel III penalty, the regulatory determination to clamp down on prop trading - commonly known as the Volcker Rule - will also negatively affect liquidity since such prop trading often serves a valuable market-making function.

This is a concern for one corporate treasurer. "The Volcker Rule, the requirement for more capital to cover derivative transactions, and the requirement for financial firms to centrally clear and collateralise, means there will generally be less liquidity in the market," he says. "We see that as an issue because it could increase the volatility of prices and potentially make hedging more expensive for us."

EACT and other bodies warn that increased additional costs to hedging and any additional liquidity risk could discourage corporates from hedging their commercial risks in what Mr Belchambers warns is a worrying and increasingly discernable trade-off in regulatory cost between basis risk and credit risk.

In a bid to seek a natural hedge for their currency risk, major exporters may ultimately move their production base to their export destinations. "That is quite a real threat," says Mr Raeburn. "Companies are saying that this is a logical outcome if they are less able to hedge."

Early problems: US president Barack Obama shakes hands with chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke after signing the Dodd-Frank Act. However, the act is regarded by some regulation lawyers as being both arcane and ambiguous

Trade finance furore

The counterparty penalty is not, however, the only means by which Basel III is likely to penalise the corporate end-client.

It is widely agreed that new Basel proposals, in terms of their increased capital requirements, will adversely affect the availability and therefore cost of corporate finance, and the corporate community is braced for a permanent increase in funding costs. "Capital is going to be much scarcer and the remuneration sought for that capital will be much higher and that will feed through to the corporates," says Martin O'Donovan, assistant director, policy and technical, at the UK's Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT).

But it is possible to identify specific, essential corporate finance products that are under threat from the new proposals.

Trade finance, a routine but vital and highly cost-effective short-term source of corporate funding, is one such product. Because trade finance items, such as letters of credit, are held off balance sheet, they may well be swept up in the Basel Committee's bid to reduce system-wide leverage by penalising all off-balance sheet items. Under the present Basel II regime, products such as letters of credit and shipping guarantees are subject to a 20% credit conversion factor which is used to adjust the risk-weighted asset calculation. Basel III, however, proposes to raise this conversion factor dramatically to 100%, which will make an already relatively low-margin product much less profitable for the banks.

The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) is deeply concerned about this issue and believes that any penalty for trade finance products under Basel III may deter banks from offering such instruments and encourage them instead to focus on higher-yield products.

Privately, several transaction bankers agree with the ICC's prognosis. According to one banker who wished not to be named, the extra constraints will have two broad consequences: first, the greater capital adequacy needs will lead to a lower availability of funds for trade finance more broadly. Second, more stringent return on capital requirements will drive-up the cost of those transactions. "My belief is that the net effect will be a tightening of liquidity available to the marketplace and trade finance in particular," he says.

Bank-intermediated trade finance underpins about 30% of world trade, according to the ICC, meaning the proposed change in the risk weighting of trade finance products could prove extremely damaging to exporters and importers globally. Thierry Senechal, banking policy manager at the ICC, adds that trade financing for emerging market transactions are likely to suffer the most under the new Basel credit conversion factor.

Thierry Senechal, banking policy manager at the ICC

The ICC recognises that the Basel Committee is not specifically targeting trade finance but rather all off-balance sheet items. However, the committee's 'blanket' approach to trade finance is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the product, says the trade body. In an argument that strongly echoes the defence of the corporate use of derivatives, the ICC disputes that trade finance is a source of major leverage since the transaction relates to tangible economic activity.

Furthermore, argue trade bodies and bankers, trade finance products are among the lowest-risk products offered by banks and are already treated too severely under the prevailing Basel II regime. "When you look at the return on economic capital for trade finance and compare that to the return on regulatory capital, the return on economic capital is about four times higher," says Karen Fawcett, group head of transaction banking for Standard Chartered. "When you translate that into what we have to charge our clients, they are already being charged for a level of risk which in reality none of the banks think exists in the system."

To bridge what Mr Senechal describes as a "big information gap" on trade finance risk data, the ICC has been working closely with the Asian Development Bank to pull together default data from a sample of some 5.2 million transactions with a total throughput of $2500bn between 2005 and 2009: the ICC found just 1100 defaults - less than 0.01%. "Our recent work shows that there is no evidence that these exposures have ever been used as a source of leverage, keeping in mind that they are supported by an underlying transaction that involves the exchange of goods or services," says Mr Senechal. Defaults during the crisis were also lower than anticipated, he notes.

The ICC has a meeting scheduled with the Basel Committee in October at which it hopes to put its case. A low appetite among regulators globally for Basel III exceptions and carve-outs, however, made the prospect of an ICC victory look uncertain at the time of writing.

Unintended consequences? The headquarters of the Bank for International Settlements, or BIS, in Basel, Switzerland, and the focal point of the Basel III proposals that have been causing concern within the private sector

Commitment issues

Indeed, the ICC is not alone in calling for exemptions and revisions to the new Basel proposals.

Another key area of concern to lobby groups relates to Basel's new liquidity coverage ratio, which ACT's Mr O'Donovan regards as a further source of additional cost for the association's members. "Because banks will not only be required to hold capital against committed lending facilities but also to hold liquidity against that facility, that will bump up the cost of all lending even of undrawn facilities," he says.

The Global Financial Market Association (GFMA) has identified one particular feature of the new liquidity ratio rules that could prove especially costly. In its international framework for liquidity risk paper also published in December 2009, Basel targets other standard funding facilities, including undrawn committed liquidity facilities banks offer to non-financial corporate customers.

The revised Basel rules assume that undrawn corporate finance facilities used for liquidity purposes, as opposed to credit purposes, will incur a 100% usage rate in situations when the market is stressed. It therefore stipulates that the banks should hold liquid assets equal to 100% of the undrawn portion of these liquidity facilities.

As presently outlined, the rule would encompass bundled multipurpose facilities - or Multi Option Facilities (MOFs) - which many corporates use for working capital, as well as back-stop liquidity lines that effectively operate as insurance when corporates issue commercial paper.

The GFMA warns that the proposal could sharply increase the cost of short-term funding for corporates, in particular the corporate commercial paper market, because the issuing company's bank would have to secure an adequate liquidity coverage ratio for the undrawn liquidity line that the issuer uses to underwrite its commercial paper programme.

In a September paper prepared by the GFMA summarising its members' response to the Basel annex of July 26 the association says: "This [liquidity coverage ratio] would require banks to split their Multi Option Facilities into separate credit and liquidity lines with increased charges applied to liquidity lines.

Not only might this negatively affect the pricing of corporate paper and the corporate paper market but this will also increase the complexity for both the client and the bank."

Because back-stop liquidity lines are a standard facility that transaction banks must provide in order to compete for corporate business, the fees associated with such lines are relatively small, says one transaction banker. But under the new provisions the cost to the bank of providing that line could rise by about 200 basis points, he continues.

"The incremental cost is not therefore something you could absorb. The facility would be loss-making unless that cost is passed on." As a result, banks may be forced to phase out Multi Option Facilities, he says.

Karen Fawcett, group head of transaction banking for Standard Chartered

No light relief

From the inevitable increase in capital costs and the counterparty credit charge, to the severe treatment of trade finance and the highly conservative liquidity coverage ratio for undrawn liquidity lines, there is plenty in Basel III to keep corporate treasurers awake at night. "It's quite right that the Basel Committee is addressing the risks," says Mr O'Donovan. "But the new rules are going to change the dynamics of corporate borrowing, even down to basic overdraft facilities," he adds.

And the impact does not end here. Assuming banks will be evermore hungry for deposit-based funding under Basel III's net stable funding regime, surely they will be willing to pay a handsome rate of interest to compete for chunky corporate cash deposits? Not so, say the regulators.

According to Bill Cuthbert, co-founder of liquidity-risk specialist consultancy Liquidatum, the UK Financial Services Authority's (FSA's) new liquidity risk rules discourage banks from rewarding their cash-rich corporate customers due to the regulatory treatment of wholesale deposits. As far as the FSA is concerned, most corporate or wholesale cash is extremely price-sensitive and not nearly as sticky or as reliable as consumer deposits - particularly in times of market stress.

Basel's liquidity risk framework, upon which the FSA's own rules are based, takes a similar view. As a result, wholesale deposits, labelled "Type A" by the FSA, will simply be less attractive to banks in future. "Type A deposits are going to be priced differently and that will affect the corporates," says Mr Cuthbert. "There are clearly going to be additional costs on the borrowing side but the one compensation for corporates on the deposit side will not be there either."

It is increasingly clear that the new post-crisis regulatory agenda looks set to transfer a good chunk of risk, in particular liquidity risk, out of the financial system and into the broader private sector. Regulators would argue that this is only appropriate since for the past 10 years bank-extended corporate funding has simply been under-priced. As a result, the financial sector has borne a disproportionate amount of the risk attached to the provision of that funding, they argue.

Certainly, European commissioners believe that derivative transactions have been sorely under-priced, and nowhere is this more evident than in the growth of non-collateralised OTC derivative deals whereby the bank effectively extends the corporate client a sizeable credit line. As with all credit lines, this must be paid for, says the European Commission. Lobbyists argue, however, that taking on corporate credit risk is simply a standard part of banking business and that in pushing risk into the private sector the regulators may be sowing the seeds of the next crisis.

The latter position may be alarmist but it is not outrageous. Regrettably for private sector lobby groups, however, concrete figures outlining the broader cost of the financial services regulatory agenda to the private sector remain thin on the ground and the generalised impact of financial regulation on economic growth is still widely disputed.

What is very clear, however, is that the regulators' wrath will not be meted out equally and that size and sector will be critical.

Large multinational companies, for example, will remain largely impervious to the new Basel III constraints, says Hung Tran at the IIF. Such behemoths are awash with cash, enjoy higher credit ratings than their beleaguered lenders and are able to raise funding in the capital markets at very competitive rates. These big beasts have little to worry about where Basel is concerned, says Mr Tran.

"However, the sector which is very important for the global economy, particularly in terms of generating employment - the small and medium-sized enterprises - are really in deep trouble," says Mr Tran. "They are very much dependent on bank lending for working capital and investment needs," he adds. As such, it is clear that the regulators are actually working against the broader political dialogue: while politicians loudly bemoan the ongoing dearth of SME funding, their agents in the financial markets are busy drafting legislation that will have long-term and far-reaching negative implications for all types of commerce. While few would dispute the need for more robust regulation, and indeed a more robust financial system at large, the corporate community should not be asked to pay for it.