Last month, The Banker examined the proposals to 'bail-in' bank creditors to avoid taxpayer bail-outs. The UK authorities have taken the lead on another aspect of post-crisis regulatory thinking, commonly called 'living wills', but a pilot project has thrown up many challenges.

Chaos is the word that Tony Lomas uses to describe the situation that he found when he led the PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) team through the doors of Lehman Brothers in London in September 2008. He had no prior knowledge or administration work plan to guide him around the operational and financial interdependencies between corporate entities within the group and across borders.

There were delays to the recovery of assets and cash to third parties while PwC sought to verify what was owed. And there were thousands of failed trades, especially derivative transactions, in which Lehman counterparties would not receive the sums for which they had contracted ahead of the collapse.

“The market uncertainty around the failure of a large counterparty to perform leaves other players with a decision about whether to hedge their position or leave it open. It led to turmoil, and that was exaggerated by so much activity being over the counter,” says Mr Lomas.

In fact, the turmoil was so severe that many governments are now determined to find methods to allow a more market-based approach to resolving Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs), without the need for large-scale state intervention.

Living wills

The UK Financial Services Authority (FSA) has perhaps led the way in its response to the problem of disorderly bank failures, and its chairman Adair Turner proposed the concept of a ‘living will’ in October 2009. This is essentially a two-part contingency plan to provide banks with a road map to navigate recovery measures in the event of severe stress, or resolution in the worst-case scenario.

A pilot project involved six UK-headquartered SIFIs submitting draft living wills to the FSA in October 2010, responding to a growing list of specific questions. The regulator is still mulling those drafts, but its questions have provided a template for other countries.

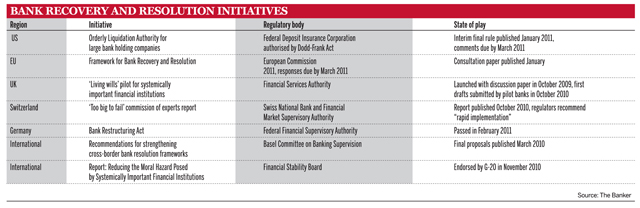

The US Dodd-Frank Act of July 2010 calls for American SIFIs to submit living wills, and the concept is also contained in EU proposals on bank recovery and resolution launched in January 2011; the Financial Stability Board recommended a similar approach in November 2010, and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision produced a paper on it in March 2010.

This means that living wills could be part of the supervisory process in the internationally agreed Basel III capital and liquidity rules.

Forward planning

“The idea is to prepare the resolution phase earlier on, rather than being taken by surprise, as with Lehman – where nobody knew the extent of credit default swap exposures, where client money was, who had the guardian or custodian position or what was the value of certain subsidiaries. There must be an alternative to bail-out or chaos,” says Rosa Lastra, professor of financial law at Queen Mary University in London, and an advisor on cross-border bank resolution to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Basel Committee.

Understandably, banks are not keen on the term ‘living wills’, with its implications of death. Duncan McNab, partner in the banking and capital markets practice at PwC, says banks around the world are also far more willing to discuss recovery than resolution. But Ms Lastra emphasises that living wills neither imply certain death, nor operate in isolation.

“For me, living wills, stress-testing, prompt corrective action, enhanced supervision and other early intervention are all part of the same family of measures,” she says.

Workflow and priorities

Following his experience with Lehman, Mr Lomas certainly believes that a living will incorporating a workflow and a set of priorities for incoming administrators could reduce (though by no means eliminate) the market disruption surrounding a large bank failure.

In a recovery situation, the existing management would retain the control structures of the bank, allowing it to operate processes in the usual way while taking corrective action. But in the event of a resolution, at present, the bank breaks down to its constituent legal entities, which raised many practical issues in the case of Lehman.

“The legal entity did not provide management information to the incoming trustee in a form that was particularly useful. The trustee has to take control of the assets, and manage the obligations, so they want a balance sheet and asset registers.

“But in a business-as-usual state, these institutions do not generate all this information in a uniform fashion, it will not be available at the touch of a button, and it almost certainly will not be available at the relevant corporate entity level,” says Mr Lomas.

Pilot banks

Alistair Asher, head of the financial institutions group at the law firm Allen & Overy, has worked with one of the six UK pilot banks on its living will, and was able to draw on his experience in advising Nationwide on its purchase of Dunfermline Building Society out of administration in March 2009.

Dunfermline is not a SIFI, but a straightforward savings institution. Yet although the deal itself was completed in a weekend, it still it took several months to tie up loose ends.

“In general, there are questions over IT licensing – at what level is the licence held and who can use it? The other area that is very tricky is the hedging. Banks will typically have a central hedging desk, which will aggregate and cover its positions in the market generally.

“So if you take a particular part of the bank’s business which has been hedged internally and try to separate it, it is hard to get the hedges to follow,” says Mr Asher.

No quick fix

This difficulty in separating hedging activities within a bank points to a wider problem. Banks, especially large international groups, are built to run with centralised functions as a way to enhance operational efficiency.

These functions may need to be broken down in order to sell off specific units, either in administration or to raise capital and avoid outright failure. But in normal circumstances, a fragmented structure – known as subsidiarisation – is not necessarily the best way to run a bank.

“One of the things that comes out of the resolution debate is that the regulator would love to have everything boxed up in nice little subsidiaries that they could separate and dispose of. It is like saying, ‘I want to dispose of each of the rooms in my house individually’,” says a senior planner for one of the six UK pilot banks.

“That would be an awkward house to live in, and a horribly inefficient use of space. You cannot say 'I will keep the bedroom and sell off the kitchen and bathroom'."

Suitable buyers

Both recovery and resolution plans are also dependent on being able to find suitable buyers for units from a distressed bank. But given the size of a SIFI, the probability is that they would enter a distressed situation during a generalised financial crisis – such as that in 2008. This makes it difficult to plan in a living will how a bank would actually be broken up, if no buyers are available.

Moreover, Sanford Brown, a partner at Bracewell & Giuliani in the US, and a former regulator with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), points out that SIFI resolution tends to lead to even more concentration in even larger SIFIs.

This is in contrast to the US Savings and Loan (S&L) crisis of the 1980s, when smaller banks were able to build up their franchise by purchasing the operations of distressed S&Ls out of administration.

“During the S&L crisis, North Carolina National Bank built itself into Bank of America on the rubble of failed institutions. But in 2008, the only banks large enough to acquire troubled institutions such as Countrywide and Washington Mutual were Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase, which were already dominant players,” says Mr Brown.

All in the timing

There is also a debate over the role of regulators in the recovery and resolution process, and the decision over when to begin enacting the contingency plans laid out in a living will.

In theory, the definition of insolvency has some legal clarity, especially if a bank fails to make a payment on its liabilities. But there is room for regulatory discretion if a bank is approaching or narrowly in breach of minimum capital adequacy and liquidity ratios.

Mr Brown says this touches on the debate about mark-to-market accounting practices, which he feels have pushed regulators to act more rigidly when working with SIFIs holding financial securities that have become illiquid.

During the 1980s, major US banks were allowed flexibility in accounting for rescheduled debts owed by many Latin American governments. This avoided major US bank restructuring until 1989, when US Treasury secretary Nicholas Brady announced his eponymous plan for repackaging the Latin American debts into bonds – at which point the most exposed banks were able to exit their positions without being forced to realise heavy losses.

Early intervention

But Ernest Patrikis, a partner at White & Case, and former general counsel to AIG and the New York Federal Reserve, argues that early intervention is best. A number of S&Ls were allowed to continue to operate while technically insolvent in the 1980s, but they actually aggravated their losses rather than recovering.

Mr Patrikis recalls a decision made while he was at the New York Fed, to cease to provide about $8bn in emergency liquidity to Franklin National Bank in 1974, at that time one of the largest bank failures in US history.

“The bank died with capital. The bank was liquidated, and there was money left over to pay the shareholders, not just the creditors. The moral is that, if banks were closed earlier, we would not have these deficits where it would be necessary for governments to step in. But there would still be valuation issues for affected assets in the market if a large institutions fails,” says Mr Patrikis.

If it is difficult to judge the timing for a bank resolution, the decision over when to implement recovery plans is even more contentious. One banker cites the example of Northern Rock in the UK, saying its business model had begun to alarm interbank markets many months before customers started queueing to withdraw their money at its branches in September 2007.

Need for flexibility

“Banks do not want to have a highly predetermined recovery plan because the circumstances are totally unpredictable, and they need the flexibility to take the right action in the circumstances. But there is also a concern about management denial; when we look at certain bank collapses, it looks with hindsight as if action could have been taken earlier,” says Mr McNab at PwC.

His colleague, Mr Lomas, adds that UK banks have been extremely reluctant to specify triggers for recovery plans, for fear that the FSA might one day seek to hold them to those triggers.

If the relationship with one regulator is problematic, the question of multiple jurisdictions brings in a whole range of new challenges. Most SIFIs are, by definition, international banking groups, and there is a general consensus that, alongside bank-drafted living wills, supervisors need to agree some international contingency plans of their own to handle a failed SIFI.

Cross-border proceedings

In theory, there is a framework for mutual recognition of cross-border insolvency proceedings, via the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (Uncitral) model law.

Major jurisdictions such as the US, Japan, Canada and Australia are signatories. But in the EU, it has only been adopted by the UK, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and – perhaps significantly – by Greece in 2010.

Francis Fitzerherbert-Brockholes, a partner at White & Case in London, made use of the Uncitral agreement when he advised on the restructuring of troubled Kazakh banks BTA and Alliance in 2009-10, which ultimately received overwhelming creditor consent.

He says the lack of mutual recognition could cause problems for a bank with correspondent accounts across the EU, as any dissenting creditors might seek to seize assets in those jurisdictions, even if the bank had the protection of courts in the US or UK.

Universality and territoriality

At the moment, the two competing principles of winding up an international bank are universality and territoriality. Under the first principle, insolvency proceedings at headquarter level should govern what happens to the whole group – something that tends to worry supervisors of jurisdictions hosting the bank’s foreign subsidiaries.

Under territoriality, every piece of the bank is handled by its individual host jurisdiction, but this is unwieldy for a SIFI with worldwide operations. Ms Lastra believes that proposals from the IMF and Basel Committee to create some hybrid between these two approaches represents the only viable solution.

“We have no hard rules for cross-border resolution that dictate what to do in the case of an institution that has branches, subsidiaries and operations in different jurisdictions.

"So you have a great deal of ring-fencing, ad hoc agreements, bargaining and uncertainty for creditors and investors. That is obviously not a desirable scenario, and the law should provide certainty, because that is when the market economy functions most effectively,” says Ms Lastra.

Confidentiality concerns

But even assuming that such agreement is possible, international supervisory co-operation is fraught with concerns for the banks themselves. In its submission to the UK’s Independent Commission on Banking, HSBC included a letter originally sent in September 2010 by its chairman, Douglas Flint, to Mario Draghi, chairman of the Financial Stability Board.

This expressed grave concerns about the confidentiality of living wills, warning that international communication must avoid “exposing the underlying firms to undue risks for either pre-emptive decisions or onward disclosure to inappropriate parties”.

Yet the concept of secret living wills has provoked scepticism among some of the banks’ own investors. Tamara Burnell, head of financial and sovereign research for £190bn ($305bn) UK fund manager M&G, says that if contingency planning is a useful exercise for management, then investors must surely be able to see the results as well.

“We think it is very important that any living will should be a public document,” she says. “If it is so market-sensitive that it has to be kept private, then in practice it is not going to work – it is going to trigger the systemic problems that you are trying to avoid.

“So we are very much in favour of banks’ publishing, and regulators permitting them to publish, how they would react in certain circumstances.”