Nigerian banks shrug off regulatory headaches

Nigeria’s banks may be suffering the impact of regulatory changes and monetary tightening, but the country’s robust growth and economic reforms are taking away the sting.

Nigeria’s banks should have few worries. Since cleaning up their balance sheets following their crisis in 2009, they have enjoyed more than two years of rapid expansion and high returns. With the economy powering ahead and new business opportunities resulting from government reforms, there seems to be little holding them back.

Yet a recent tightening of regulations and monetary conditions has made life harder for banks. Last year, the Central Bank of Nigeria cut the amount banks were allowed to charge customers for withdrawals and hiked its cash reserve requirement (CRR) for public sector deposits, which make up a large chunk of those in the banking system. Another blow came with an increase in the so-called Amcon levy, which commercial banks pay to fund the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria, the state-owned bad bank set up in the wake of the crisis.

These factors have already caused headaches for banks. Their profits for the third quarter of 2013 were down and investors, who were previously piling into banking stocks, turned bearish at the start of 2014. By mid-March the shares of Guaranty Trust Bank (GTB), Zenith and First Bank, the country’s biggest lenders by market capitalisation, had fallen year-to-date by 10%, 19% and 26%, respectively, according to brokerage African Alliance.

Part of the sell-off was triggered by rising political tensions ahead of elections in early 2015 and the president’s controversial suspension of Lamido Sanusi, the central bank governor, in February. But analysts say that concerns about banks’ ability to sustain their earnings growth have weighed heavily on the market.

“This year is going to be even tougher than 2013,” says Vivien Shobo, head of Agusto & Co, a Nigerian rating agency. “Banks’ revenues and profits are under huge pressure. With the reduction in commission on turnover and the hike in the CRR, the main issue for them is how to replenish the lost revenues.”

Lowering commissions

Of the changes, bankers seem most irked by the lower caps placed on commission on turnover (COT). The central bank lowered these caps as part of a push to deepen financial inclusion in Nigeria, where barely a quarter of adults have bank accounts. Saying that excessive bank charges put people off opening accounts, it reduced COT rates from 0.5% to 0.3% of transactions last year. By 2016 they will be removed completely.

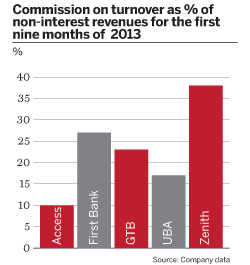

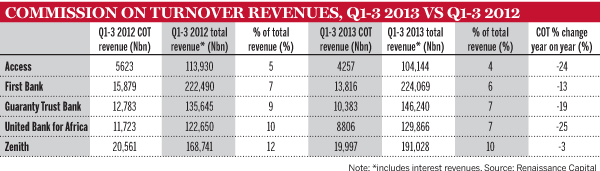

The losses to banks have been hefty (see table). Many were until recently deriving more than 20% of their non-interest revenues from COT (see chart). “It was a fairly essential source of revenue for some of the big banks,” says Adesoji Solanke, an analyst at Renaissance Capital.

Some argue that phasing it out will work against the central bank’s aims by discouraging investments in new branches and ATMs, particularly in remote areas. “The central bank’s measures have had a disproportionate effect on banks with a strong retail market presence,” says Bisi Onasanya, managing director of First Bank, Nigeria’s biggest lender by assets, according to The Banker Database. “In some instances, they appear to punish the large investments in the infrastructure necessary to push the frontiers of banking in the country.”

The increase in the annual Amcon levy and the CRR could prove similarly problematic. The former was put up from 0.3% of each bank’s assets to 0.5% in 2013. FBN Capital, the investment banking arm of First Bank, thinks that the cost to the sector for 2013 will be $660m. Moreover, with the levy in place for the lifetime of Amcon, which is only expected to wind down in 2023, it is not a short-term issue.

Bankers mostly agree, however, that it is a price worth paying to fund an organisation that played a vital role reviving the industry by its purchase of billions of dollars’ worth of non-performing loans in 2010 and 2011. And they will be encouraged by a pledge from Amcon’s boss Mustafa Chike-Obi: “The levy won’t rise above 0.5%.”

Tying up reserves

The CRR has been used by the central bank as a monetary tool to combat an increase in liquidity and a weakening currency. In July last year it raised reserve requirements for public sector deposits from 12% to 50%, and followed up with another increment to 75% this January. Some analysts estimate the moves would have forced banks to place an extra N1500bn ($9.3bn) in the central bank’s vaults, money that they could be earning high interest on elsewhere.

Bankers were hardly pleased at first. Kingsley Moghalu, deputy governor of the central bank, says they “screamed murder” when the CRR was changed to 50%. But they have since backed the policy, believing it necessary in light of the central bank’s mandate to ensure exchange rate and price stability. “We feel the pinch like every other bank, but we understand the rationale,” says Patrick Akinwuntan, a Lagos-based board member of pan-African lender Ecobank, which has a large Nigerian subsidiary.

With the naira still under pressure and portfolio inflows dropping, the central bank could tighten monetary policy again in the next few months. Many banks anticipate that the CRR will be increased to 100% for public sector deposits and from 12% to 15% for private sector ones.

The rise in the CRR has made banks, which have tended to rely heavily on deposits from the federal and state governments, try to generate more liabilities from the private sector. To succeed in enticing more people and companies to bank with them, higher deposit rates will be necessary, but probably insufficient. “The reality is that they will have to pay more attention to things such as customer service, which some of them haven’t been doing much,” says Mr Solanke.

A few banks will have the added inconvenience of having to raise capital in the near term. Nigeria’s banking sector had a high capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 18% at the end of 2012, while the largest eight lenders by assets probably have a CAR of more than 20% today, according to central bank data. But the Central Bank of Nigeria recently deemed those eight – First Bank, Zenith, United Bank for Africa, Access, GTB, Ecobank Nigeria, Diamond and Skye – as systemically important and stated that they should have minimum CARs of 15%, compared with 10% previously.

Diamond and Skye, which have the most pressing capital needs, are expected to raise a mixture of equity and Tier 2 debt in the next six months. Others might be compelled to do the same if their CAR drops below 20%. “If you have a CAR of 17%, which looked very comfortable before, now you only have a small amount of headroom,” says Bolaji Balogun, chief executive of Chapel Hill Denham, a local investment bank. “It would mean that you’ve likely got to do something.”

Strong position

Yet for all the headwinds, Nigerian banks are in a strong position and are still able to make plenty of money. Zenith and GTB, the first two banks to report 2013 results, made returns on equity of 20% and 30%, respectively. Executives at the bigger lenders are confident they can generate returns on equity in the region of 20% at least in the medium term.

Much of the optimism stems from Nigeria’s real growth rate of 7% and inflation having dropped from 13% to 8% in the past two years, according to Standard Bank. Reginald Ihejiahi, who retired as managing director of Fidelity Bank, a mid-tier lender, in February, says that thanks to macroeconomic stability, bankers are today far more comfortable funding long-term projects. “Ten years ago, banks were very short term in their thinking,” he says. “That was because of their perceptions about the economy. They weren’t keen to take certain kinds of risks. Today, that’s changed. Some of that is coming from [improvements in the way] policy-makers are handling the economy.”

The confidence is also a result of structural reforms, which have opened up many banking opportunities. Mr Ihejiahi says local content rules, which have led to the birth of several indigenous oil producers, have enabled Nigerian banks to play a much greater role in the upstream oil and gas sector, hitherto dominated by foreign institutions.

Similarly, banks have benefited from power reforms. Last year the government privatised 14 generation and distribution companies as part of efforts to end Nigeria’s dire electricity shortages. Godwin Emefiele, head of Zenith and the person nominated by the president to replace Mr Sanusi at the central bank, says that lending to investors in these power companies has helped his firm offset developments such as the decrease in COT.

Low penetration

Others point out that the banking sector is attractive precisely because financial penetration is so low. Of a population of 170 million, only about 17 million people are thought to have bank accounts. Mr Balogun of Chapel Hill Denham says that number could easily increase, especially if banks did more to tap the 100 million-odd Nigerians that own mobile phones. “The number of bank accounts in the country could move to 30 or 40 million in the next five years if the banks go about it the right way,” he says.

The prospect of that happening is one of the reasons he thinks the industry can continue expanding quickly. “We’ll see fairly aggressive growth for a while,” says Mr Balogun. “And even when that tapers, I don’t see assets growing at less than 15% annually.”

For Nigeria’s banks, the next few years could thus prove exciting, even if numerous regulatory and monetary changes throw up unwelcome challenges at the same time.