As financial services firms are bombarded by new regulations, they are being forced to change their methods of reporting. This is generating a massive shift in IT investment, says Anthony Gandy.

The problem with regulation is not that there is so much of it but that it is changing so often. Financial services firms are assailed from all directions. Not only do they face the same changes everyone else does in dealing with governance rules, accounting standards and data rules, but they also have to face the problem that many of these changes affect them to a much greater degree than they affect many other firms. The technological morass this is creating is forcing firms to try to create new reporting environments and to question whether old core systems deliver the performance, flexibility and structures that will fulfil the needs of the many new regulatory requirements. Traditional systems offer neither the flexibility nor the speed required by the new regulatory regimes that banks now have to deal with. This is not just an IT issue, however. New regulatory environments are focusing the minds of senior staff on dealing with the challenges that have been created. New penalties mean that the issue of compliance and the IT systems that support compliance and regulatory reporting are a very personal matter for senior management. “There are clear penalties for firms not getting compliance right,” says Jenny Knott, head of finance at Nomura International. “For the firm, they are reputation risk, leading to a negative impact on share price, ratings, revenues, costs (eg. cost of funding), recruitment and, potentially, restatement of the accounts. For the individual, there are also growing penalties. Under the US’s Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, falsely certifying accounts can lead to a fine of up to $1m or 10 years in jail – or both. If this false certification is proved to be wilful then the fine is up to $5m and/or, 20 years in jail.” Overlapping requirements But there is more to it than just Sarbanes-Oxley. Banks are assailed by regulatory requirements that overlap across geographies, across sectors and across responsibilities. Key changes that have major international impacts include:

- prudential rules and financial regulations, such as Basel II;

- corporate governance rules, such as Sarbanes-Oxley and the Directive on Statutory Audit – the EU version of Sarbanes Oxley, which is aimed at stopping the next Parmalat;

- International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS/IAS);

- anti-money laundering legislation, such as EU Money Laundering Directives, US Patriot Act, Proceeds of Crime Act.

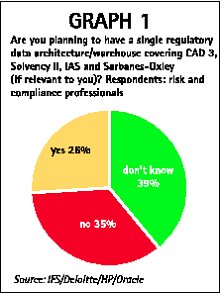

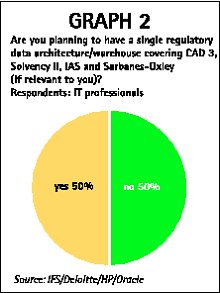

These regulations create an enormous challenge because they take such a different approach from past regulations. Basel II is the most all-pervasive regulatory change that the industry is facing. It is a clear illustration of how regulations are changing in operation. “The proposals specifically address regulation of internationally active banks,” says Ms Knott. “However, the spirit will pervade through to investment banking regulation. The old Accord (Basel I) focused on a single measure of risk, it was one size fits all and it was very broad brush. The new Accord is focused on internal methodologies, is more flexible and more risk sensitive.” Under strain Many other regulatory changes – from elements of anti-money laundering to new accounting calculations to governance rules – reflect a general move towards a greater risk sensitivity and flexibility. However, they also put immense strain on institutions that do not have information frameworks that can deal with the new forms of regulatory requirement in place. Firms not only have to provide a series of static reports showing their positions and populating reports and accounts. Now, data needs to be analysed and operated on in short timeframes. Reporting options Firms have many options for delivering a regulatory reporting environment that are able to provide the regular reporting and ad hoc query capabilities needed to comply with the regulators’ demands. They could patch current reporting systems; they could provide a new regulatory reporting utility, storing all relevant regulatory data drawn from current regulatory and core systems; and they could re-engineer core systems to provide this central data store. Whether the latter two options are possible depends on who is being asked. There appears to be a major divide between two key communities: compliance and risk officers on the one hand, and IT managers on the other. A survey by the UK’s Institute of Financial Services (IFS) of 72 institutions covering all three types of professionals has revealed that half of the IT management of financial services companies want to implement a strategic solution dealing with regulatory change by implementing a single regulatory reporting utility (see graph 1). Only 26% of compliance and risk professionals believe that their firms would achieve this goal, according to the survey (see graph 2).

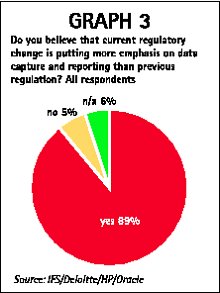

Fix it first Many compliance and regulatory professionals seem to believe that fixing old systems will be the best and cheapest route to compliance. Roy O’Neil, principal of Deloitte’s financial services practice, says: “There is clear logic in building a single regulatory environment. However, there are a number of issues. There still remains a clear demarcation of regulatory responsibilities in certain parts of the industry. Data quality, better reporting and, of course, the size and nature of the business still get in the way.” Not surprisingly, given that these hurdles exist, many institutions are in effect being forced to adapt current systems to deal with the burgeoning number of regulatory changes. However, this may not be best suited to the new forms of regulatory reporting. The nature of what the regulatory systems have to achieve has changed dramatically in the past few years as new requirements have developed. The key change is that regulatory systems are now no longer restricted to producing regular reports. Instead, regulatory systems, or at least the systems that feed into them, have become a part of the decision-making environment of the institutions. For example, under Sarbanes-Oxley, results have to be produced more quickly than in the past and ad hoc reporting could be required. Part of the legislation – S409 – demands that firms must provide for rapid and current disclosure of material changes in financial conditions and operations. Similar problems occur when considering anti-money laundering requirements. Not only do banks have to search for anti-money laundering activity, they will need to make some real decisions in near real time. Systems have to help bank officers decide which customers they should take and which they should not. According to David Curd, chief information officer of Barclaycard: “Regulation is not a standard question. We will often have to make ad hoc requests. We have the data but getting access to it is not easy. It is likely that we will need a new utility for business intelligence that will give us access to regulatory data. It needs to be an environment that allows us to make real customer decisions, as well as supporting regulatory reporting. We need to make customer-facing decisions, such as looking for potential fraud, making credit risk decisions and how we can extend business with customers.” Data collection changes This requires a new approach to using regulatory data, says Mr Curd. “You need an environment that has the right data messaging and API [application program interface] environment to collect the data that you require. Then on the other side, you need to be able to play back that data to the channels so that they can make decisions. The core banking systems are seven to 10 years away from this. A separate regulatory utility is needed.” The IFS research shows that the collection of data has become a key driver for firms as they work out methodologies to deliver regulatory reporting capabilities (see graph 3). Mr Curd is adamant that the challenge is not only to capture and store data, but also to make it available in new and flexible ways.

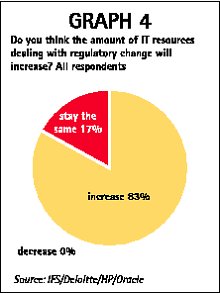

Whichever path is chosen towards complying with the burgeoning number of regulatory requirements, the sheer volume of change is generating a massive shift in IT investment. Discretionary spending is going towards dealing with regulators and away from business development. The IFS survey shows that not one person interviewed thought that investment in regulatory systems would decrease in the medium term – 83% could only see it going up (see graph 4).

As financial services companies are increasingly required not only to analyse data but also to actively use and feed it back to people in the front line, regulatory systems will need to be able to communicate more directly with the core banking environment so that they can capture information as and when it is needed. A lot more storage and computing power will be needed than has been required traditionally. It is a new model and one that will be difficult to achieve with many old environments. Such changes are also closely related to others going on in core banking systems. There is an increasing migration to core banking systems that put data at their core. This has usually been seen as a way of providing customer-focused core systems. There is, however, an increasing need to regard this operational data store as a key resource for many different regulatory and risk control requirements, be it checking for anti-money laundering activity to deciding how much capital will be needed to back a loan. Implementation: the challenge for banks with global reach While Sarbanes-Oxley may be focusing the minds of the CEO and the CFO, and Basel II occupies the minds of nearly the whole industry, individual responsibility does not stop there. Chief information officers are also becoming increasingly responsible, on a personal level, for ensuring that regulations are adhered to. The problem is that they, like CEOs and CFOs, have to beware of regulations that have been written thousands of miles away and that, on first sight, may not appear critical. “It used to be that IT directors could let the legal department worry about the law, while they worried about technology,” says Michael Colao, director of information management at Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein. “Now, there are a variety of legal pitfalls that can ensnare a chief information officer. Worse, many of them are in areas where they have full responsibility, but little or no operational control.” In the UK, chief information officers will be directly concerned with the following:

- the Data Protection Act 1998, covering privacy and data protection;

- the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, on investigating employee misconduct;

- the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, over rights management, licensing and piracy;

- the Computer Misuse Act,1990, tackling hacking.

However, many banks are global and they have to implement hundreds of different laws. Can they really implement them only on a local basis? According to Mr Colao, the answer is no. “If you store any personal data on any California resident and there is any breach, theft or loss of that data, then you have a legal requirement to inform all affected persons immediately after discovering the breach, according to California SB 1386. “We are a global bank, we have customers everywhere. Therefore local laws such as SB 1386 do end up affecting us and, worse, they become global in reach. I would not want to deal with the impact to our reputation if we were to ever experience a security breach and then only tell our California customers about it. The California law in effect requires us to tell all of our customers. It becomes de facto, if not de jure, a global law.” Chief information officers also have to deal with a large number of contradictory requirements. Accessing staff e-mails in the UK is possible if an employer complies strictly with the requirements of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act. In Spain, a court order is needed. In France, it is abhorrent to think that an employee’s privacy is breached. Sarbanes-Oxley may make the CEO and CFO eye Alcatraz nervously and maybe they should sweep out the cell next door for the chief information officer. But the law is also a lesson in how regulation is controlled by the regime with the most Draconian or customer-friendly set of rules. This becomes the norm for operations on a global basis. For international banks and for investment banks with dozens of different locations and regimes to satisfy, the challenge this presents is enormous.