The process of risk-weighting assets to determine banks' capital adequacy has attracted criticism, but European regulators are keen to improve rather than eliminate it.

Banking is all about measuring and managing risk: the risk of borrowers defaulting, of interest rates changing and, for the largest systemically important financial institutions, of financial markets moving. And yet, bankers and regulators are locked in a fundamental debate about how to measure risk to assess each bank’s capital needs.

Editor's choice

At the heart of this debate is the process of risk-weighting assets to decide how much capital banks need to hold against them. This was the central innovation of the global Basel II agreements on capital regulation compared with the previous Basel I deal, but there are growing complaints that banks are manipulating the process to minimise their capital requirements. At one stage in 2011, the divisions among national supervisors meeting at the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision became so severe that they called in an external peace-maker in the form of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Researchers at the IMF assessed whether there were sharp divergences in the way different banks and their home supervisors calculated risk-weighted assets (RWAs) and, if so, what could be done about it.

Work in progress

The IMF eventually published its report in March 2012, concluding that there were some specific causes for concern. The use of foundation and advanced internal risk-based models of RWAs by the larger systemic banks gave significantly different outcomes from standardised RWA calculations based on parameters set by the regulator or third-party credit ratings. Some banks saw sizeable swings in RWAs over time without conducting major changes in their business mix. And RWAs for certain banks sometimes differed sharply from peers in the same or other jurisdictions.

The IMF report was constrained because it had to be based purely on publicly available data, which did not include the more granular loan-level analysis made available confidentially to supervisors. Still, it broke the deadlock. A month later, the Basel Committee established its Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP). By July 2013, RCAP had produced its own report on divergences in the measurement of credit RWAs, which typically account for 80% of total RWAs or even more for smaller banks. Researchers of the RCAP report were given access to the more detailed supervisory data.

This report made use of a hypothetical portfolio exercise, a technique originally adopted by the UK’s Financial Services Authority. Banks are given a sample of exposures (ideally including at least some that they actually have in their real portfolios) and asked to risk-weight them using their internal risk-based models.

Assuming all the banks started with a capital adequacy ratio of 10%, the report normalised capital ratios for all 32 banks in the sample by reweighting their assets to the median risk weights for the hypothetical portfolio. The conclusion was that “the capital ratios of most banks (22 of the 32 participating banks) would lie within one percentage point of a 10% risk-based capital ratio benchmark. However, risk-weight variation could cause the reported capital ratios for some outlier banks to vary by as much as two percentage points from the benchmark (or 20% in relative terms) in either direction.”

Transatlantic rift

Is this cause for concern or reassurance? The answer to this question is likely to depend on which side of the Atlantic you reside. US regulators have historically placed greater emphasis on pure leverage ratios – capital as a percentage of assets, without the risk-weighting process. Europe was more favourable to risk-weighting, and adopted Basel II well before the US. American regulators had only just begun to impose Basel II requirements when the financial crisis broke in mid-2007 and prompted a complete review, leading to Basel III, which is due to come into force by 2019.

The Basel III framework proposes using both techniques, with the risk-weighted capital adequacy ratios refined from Basel II alongside a new simple minimum leverage ratio of 3% capital to assets. In keeping with their traditional focus, the US authorities are already proposing to hold their banks to a tougher 5% leverage ratio – or even 6% for foreign subsidiaries.

“If one ratio takes precedence, banks will tend to adapt their business model only to that ratio; they will manage according to the most biting regulatory constraint. So US banks have tended to focus on limiting total balance sheet size, whereas European banks have allowed balance sheets to grow larger relative to capital, but paid more attention to the perceived riskiness of their assets,” says Vanessa Le Leslé, senior financial sector expert at the IMF and co-author of its March 2012 report.

The criticism from US banks is that the focus on risk weighting has allowed European banks to leverage up far more than their American counterparts by running with much lower levels of RWAs as a proportion of total assets. On a superficial examination, this appears true. Using data from thebankerdatabase.com, for the top four US universal banking groups by assets (JPMorgan, Bank of America, Citigroup and Wells Fargo), RWAs were equivalent to 58% of total assets in 2012. By contrast, for the top five European banks by assets (HSBC, Deutsche Bank, Crédit Agricole, BNP Paribas and Barclays), the ratio was just 27.5%. In short, it looks as if European banks are able to hold about half as much capital against each dollar of assets, due to their more aggressive approach to risk weightings.

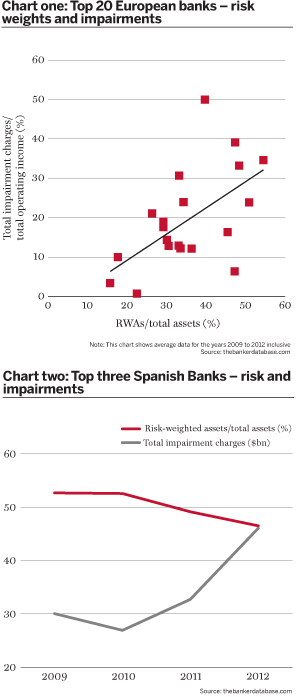

But there is evidence that European banks are assessing risk correctly. If RWA modelling is working, then the ratio of RWAs to total assets should correlate with each bank’s risk appetite, underwriting standards and ability to recover defaulted assets. These could be measured by total impairment charges. Running the averages of these two indicators for the top 20 European banks by Tier 1 capital for the period from 2009 to 2012 suggests this correlation is fairly strong (see chart one).

Certain banks with noticeably low RWAs to total assets, such as Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse, have also booked very low impairment charges over the period. The few outliers usually have a specific explanation. Lloyds Banking Group has suffered unusually high impairments, but much of this is to do with the assets inherited from its acquisition of HBOS, rather than Lloyds’ own underwriting standards.

Accounting for taste

The focus on a specific ratio – pure or risk weighted – not only influences capital management strategy, but even the accounting standards preferred. In Europe, where total balance sheet size has taken second place to RWAs, International Financial Reporting Standards require banks to gross up their derivatives exposures. In the US, where leverage matters more, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles allow banks to net out derivative positions and collateral in calculating their total assets.

The Basel Committee is attempting to push for more uniformity, but any inclusion of gross derivative positions for US banks could be highly contentious. In a report in May 2013, financial services-focused investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods (KBW) calculated that the adoption of the proposed Basel III leverage ratio methodology, and the resulting increase in total assets, would on average shave more than 100 basis points off the leverage ratio of systemically important financial institutions in the US. Of the four largest universal banks, only Wells Fargo would have a leverage ratio stronger than 6%. It would also make the US banks’ proportion of RWAs to total assets look rather less conservative.

“Most of the focus has been on prudential requirements and global convergence on accounting standards has really stalled. But this is an area of fundamental importance, the netting of derivatives is one of the most salient questions and any contribution that the Basel Committee can make to resolving this is very valuable,” says Ms Le Leslé.

Promoting risk management

What of the investors and analysts who must ultimately put client money at risk, buying shares or bonds issued by banks? There seems to be broad support for the principle of risk weighting. Logically, a mortgage extended to an owner-occupier with a low loan-to-value (LTV) ratio is less likely to default, and therefore needs less capital held against it than a buy-to-let mortgage or one with a higher LTV ratio.

Andrew Stimpson, European banks strategist at KBW, does not favour hiking the leverage above 3%. “The leverage ratio can work as a backstop, but once it rises over 3%, it is likely to distort incentives and encourage banks to raise risk in order to increase return on a smaller asset base. That takes us back to a world where a 50% LTV mortgage is treated the same for capital management purposes as a 120% LTV mortgage, which is what got some banks into trouble in the first place,” he says.

Orchestrated by the European Banking Authority (EBA), the European supervisors are fighting their corner in support of RWAs. The EBA produced its own top-down report on the consistency of credit risk-weighted assets in February 2013. It is now working on bottom-up surveys of low-default assets (sovereigns, financial institutions, large corporates and infrastructure projects), the more granular portfolios (mortgages and small businesses) and market risk in the trading books. The initial top-down survey suggested that 50% of the divergence in RWA measurements could be explained easily by individual factors such as the roll-out of advanced internal risk-based methodology and a different business mix compared with peers. In the third quarter of 2013, the EBA plans to release a second report looking at the other 50% of differences that cannot be explained so easily.

“It is not about naming and shaming banks, it is about identifying how factors such as collateral levels differ between banks or possibly areas of divergence in practice. If necessary, we would think about improving supervisory consistency. Achieving this kind of transparency is vital and more helpful than just scrapping risk-based measures and causing banks to ramp up risk,” says Piers Haben, director of oversight at the EBA.

Enhanced disclosure

The EBA’s development of a single European rulebook, due in 2014, will boost both transparency and consistency – at present there is not even a single European definition of what actually constitutes a non-performing loan. Both the EBA and the Basel Committee are also reviewing the rules regarding trading books. This is a relatively small element of the picture, mostly affecting the largest systemically important financial institutions only. Market RWAs account for less than 7% of total RWAs in western Europe and North America, with the highest proportion in Europe (at UBS) reaching 17.4% of total RWAs. But the discrepancies in measurement can be severe. The Basel RCAP produced a report in January 2013 using a hypothetical portfolio exercise, which showed average market risk weights varied from 10% of total exposures to 80%, with most banks between 15% and 45%.

“The distinction between the trading book and the banking book has a very significant impact. We are expecting a second paper from Basel on its fundamental review of the trading book later in 2013 that is likely to have a major bearing on capital requirements for trading book exposures, and potentially on the classification between banking and trading books,” says Frédéric Gielen, a partner at financial risk consultancy Avantage Reply and former regulatory expert at the World Bank.

Some of these differences in classification can be highly significant. Most supervisors require banks to categorise unconsolidated minority equity stakes in other financial institutions as market risk – the value of the stake will move with the stock market valuation of the listed equity. France allows its banks to place strategic equity stakes under the banking book. In the case of one French bank, reclassifying unconsolidated equity stakes would increase market RWAs from the $38.5bn figure used in the January 2013 RCAP report to $64.3bn.

The process of standardising reporting is also viewed very favourably by investors and analysts, and Basel’s Enhanced Disclosure Task Force initiative is widely welcomed. In some cases, banks are moving ahead of regulators in providing information on RWA variations and their causes. Australia’s Commonwealth Bank included in its 2012 annual report a table showing that RWAs on its mortgage book consumed 1.6 percentage points of extra Tier 1 capital in Australia than they would in the UK, because the Australian regulator places a floor of 20% on banks’ loss-given-default assumptions, whereas the UK authorities use a floor of 10%.

“The banks are producing very comprehensive 100-page reports on their RWA calculations under Basel Pillar 3 disclosure, so the transparency is there. What would help is greater standardisation in the disclosure, because each bank is different, for example on whether or not it includes defaulted exposures in its risk weights,” says Mr Stimpson.

Harmonisation versus discretion

The comparison of Australian and UK regulations demonstrates clearly why harmonisation may face challenges. National supervisors want to retain the discretion to take corrective action over the banks in their jurisdiction.

“One area of uncertainty is how the domestic stance on internal models will work alongside the EU’s Capital Requirements Directive [CRD IV] and Regulation pan-European framework that removes quite a lot of national discretion from the equation,” says Mr Gielen.

In May 2013, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA) imposed a floor on the risk weighting of residential mortgages at 15%, after observing that the largest banks using internal risk-based methodology had assigned risk weights of 5% to 8%, compared with 35% using the standardised approach. Before the new floor, banks were required to base their probability of default and loss-given-default assumptions on a historical period that included not only the current global financial crisis, but also Sweden’s own crisis in the early 1990s. Even then, explains Uldis Cerps, executive director of banks at the Swedish FSA, the average loss on gross mortgage exposures over a three-year period was just 0.75%, giving rise to ultra-low risk weights.

“During the past 20 years, we have seen higher LTV ratios, higher household debt levels, a constant rise in house prices over a long period of time and a somewhat weakened social security system. Combining all those factors, there is a good reason to think that future losses might exceed those we had in the early 1990s, and to base our estimate of capital needs not exclusively on historical data, but also on judgements about the future,” says Mr Cerps.

Although he has adjusted risk weights for the idiosyncrasies of the Swedish housing market, Mr Cerps is still a strong supporter of European and international supervisory harmonisation on RWAs. Other supervisors are already actively comparing RWA models on a cross-border basis. In June 2013, the Danish FSA ordered the country’s largest bank by Tier 1 capital, Danske, to increase risk weights on its loans to large domestic corporates. Ulrik Nødgaard, director-general of the Danish FSA, says his organisation now devotes more resources to looking beyond validating models equation by equation, and adds a top-down assessment comparing the results between banks.

“We hear from every bank that they are unique, their clients are better and the way they recover assets is more stringent. But we would find it very hard to understand why, for instance, for their large business clients Danish banks have smaller risk weights than those in Sweden or Norway, even though the economic environment is more favourable in Sweden and Norway. We need to take a step back and ask if these results make intuitive sense. We cannot accept the premise that every bank is unique and if there are significant differences then we need to question them,” says Mr Nødgaard.

Too much detail?

In addition to cross-border variations, changes in RWAs over time are drawing more attention. Following the EBA’s imposition of a new 9% capital adequacy ratio in 2011, Spanish banks faced international criticism for finding part of their capital needs by lowering risk weights at a time when the risks in the Spanish economy appeared to be rising. The top three banks saw a decline in the proportion of RWAs to total assets, directly preceding a sharp rise in impairments in 2012 (see chart two).

“The intertemporal aspect of RWAs is absolutely key. Of course, we have seen some deleveraging by European banks that may include switching from riskier to less risky assets, so I would avoid simple interpretations of what is going on over time, but it is right to ask the question and to seek to improve transparency,” says Mr Haben.

However, it would be unrealistic to think that the increased regulatory scrutiny of risk weights alone will eliminate RWA optimisation as a strategy for improving bank capitalisation levels. Bank executives want their institutions to grow and to offer a decent return on equity to investors.

“There is no question that the pendulum is swinging; banks are having to build risk weights using 2008 to 2009 loss data, which is gruelling, and that puts them under pressure to raise capital at a difficult moment. But of course, from Europe to Asia to the Americas, banks want to maximise their business franchise and optimising capital consumption will always be one obvious way to achieve that,” says Andre Horovitz, an independent consultant who was previously a chief risk officer at Credit Suisse and Erste Group Bank.

With that in mind, attention to corporate governance must not be neglected in the process of improving the credibility of RWA calculations. Ensuring that banks have the right framework to manage risk could be more effective than regulators trying to control the RWA modelling process through any number of floors and cross-border comparisons.

“If the rules become too prescriptive, banks tend to comply with the letter of the regulation without genuinely calculating and managing risks themselves. Already, banks are likely to have one team for regulatory reporting and compliance, and another for internal risk management that are largely isolated from each other. We must encourage banks to manage risk and capital together,” says Ms Le Leslé.