What would a Brexit mean for the City of London?

The UK’s relationship with the EU may be coming to an end, with British people voting on whether to leave the bloc on June 23. Silvia Pavoni looks into the uneasy alliance, the financial regulation that clouds the picture and the prospects for the City of London outside the single market.

As the print version of The Banker's June 2016 edition makes its way across the globe, the UK – where the magazine is based – will have entered the final, decisive few weeks before the date of the referendum that will ask the British people to vote on whether or not they want to be part of the EU.

Far from being a niche issue, 'Brexit' has engaged leaders the world over. US president Barack Obama, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe and International Monetary Fund managing director Christine Lagarde have urged the UK to stay in. Russian president Vladimir Putin has backed suggestions that the country should leave.

Research papers have been released in quick succession to support either side of the argument and demolish the other camp’s assumptions as battle intensifies. The UK Treasury has warned of permanent economic damage should the country vote to leave on June 23, as has the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Newly created groups such as Economists for Brexit and Historians for Brexit have strongly backed a parting of the ways with continental Europe.

Among the bones of contention regarding a Brexit are sovereignty and economic prosperity. The ‘out’ campaign exploits fears of uncontrolled immigration, bemoaning the fact that policies on this and other key issues are defined by Brussels rather than Westminster. It also points to the disharmony between what it sees as a pro-market UK and a more 'protectionist' Europe. Meanwhile, concerns about rising unemployment and loss of international trade and investment are the ammunition of the ‘in’ team. Fears of a domino effect on other countries considering their own exit and global geopolitical tensions have also been thrown into the debate.

But away from the headlines, there is a more technical but equally important side to Brexit: what would happen to the City of London should the UK cut loose from the EU?

Time for a break?

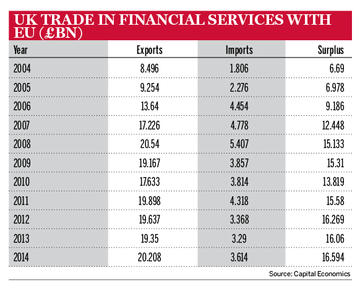

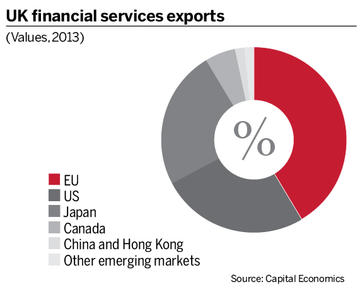

The UK is a net exporter of financial services. In 2014, it registered a £72bn ($104.3bn) financial and related professional services’ trade surplus, a figure larger than the combined surplus of all the country’s other net exporting industries. The EU is the largest net buyer, resulting in a £18.5bn surplus for the UK, according to data released by TheCityUK, the body representing London’s financial services firms. Consultancy Capital Economics has a slightly lower figure for 2014, £16.6bn, but confirms that the EU is indeed the largest destination market for British finance: 41% of financial services exports, compared with the 26% share absorbed by the US.

Much of this success originates in London, which has become a benchmark for what an international financial centre should offer: a nimble legal system, market-friendly policies, openness to foreign firms, a wide and deep network of ancillary services and a large pool of talented and international finance professionals. Brexit supporters say that the City will continue to prosper outside the trading bloc because of these intrinsic values, while their opponents warn that London is an unbeatable proposition for foreign investors only when coupled with access to a market of 500 million people, their savings, businesses and transactions, which the EU provides.

Pro-Brexit campaigners insist that diverging views have damaged the UK's relationship with Brussels beyond repair. Patrick Minford, professor of applied economics at Cardiff Business School and co-chair of the Economists for Brexit group, has been uncomfortable with the actions of the bloc since the late 1980s, when president of the European Commission Jacques Delors began to push an agenda of stronger integration, which included the creation of the euro. “That’s been the direction of the EU ever since – these grand people, who want to rule over us with their socialist ideas,” says Mr Minford.

Renegotiation tactics

Regardless of ideological frustration, cutting trade ties with the EU would, at least in the medium term, have a negative impact on the UK economy. Renegotiating them would equate to filing for divorce while seeking a different kind of relationship with the same partner. Jonathan Hill, the British politician who serves as European commissioner for internal markets, finds this proposition absurd. “The idea that is sometimes advanced that if the UK left you could quickly come to an agreement with the rest of Europe that would be at least as good as the current one in terms of access to the single market, I think it is completely for the birds,” he says.

All 28 EU member states trade their goods and services freely among each other. This applies to financial services too. A US bank, for example, can serve European clients from its London office without needing additional authorisation. It can sell banking or investment products to corporate or retail clients in, say, Germany without the formal approval of German banking authorities and even without a physical presence in the country. This is called passporting, and essentially has the same effect on financial services as a free-trade agreement (FTA) has on goods. Financial services, in fact, are not traditionally included in FTAs.

Such passporting rights are provided by the Capital Requirements Directive, now in its fourth iteration. Similarly, the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive 2, the Undertakings for Collective Investments in Transferable Securities Directive (Ucits) and the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive grant similar rights to investment firms; Solvency II allows insurance companies to passport their services throughout the single market; and payments and e-payments firms can passport theirs thanks to the Payment Services Directive and the Second Electronic Money Directive, respectively.

Passport control

Other areas of finance benefit from the single market too. Being part of the EU has allowed the UK to continue with the clearing and settlement of large amounts of euro-denominated transactions, as ruled by the European Court of Justice in 2015 in response to a complaint by the European Central Bank. A Brexit would likely overturn that decision. It would also deny passporting rights to the same US bank that runs its European base from London and which may chose to relocate the regional headquarters elsewhere inside the EU or spread subsidiaries across a few key markets. The same could be true for European banks that choose London as the centre for certain operations. Assets of the largest foreign bank subsidiaries in London amounted to about $1500bn or 20% of total banking assets in the City, according to The Banker Database.

A survey conducted by the British Bankers’ Association in March revealed lenders’ concerns: most respondents said a Brexit would damage their organisations. James Grand, partner at law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Dereinger, says: “On a purely legal analysis, from a regulatory point of view, leaving the EU is about the most damaging thing you can do to the City of London. It simply takes away the certainty of the market. It takes away the authorisation to sell financial services to the rest of Europe.”

Mr Grand is a member of the Lawyers Group of British Influence, an organisation opposed to Brexit. Because of the uncertainty on what a Brexit deal would look like, along with the timeframe required to reach an agreement, clients are left unable to build contingency plans.

“The only certainty is that if the legal basis on which they currently offer their services is going to be pulled from under their feet, their business will have to change very quickly,” says Mr Grand. “The one thing that we definitely know works as an option is moving the business abroad, to a jurisdiction where you can be fully authorised and therefore have access to the European market.”

Model options

When it comes to potential alternative models for the UK to follow should it opt to leave the EU, Norway's is the most commonly cited. The country is not an EU member but is part of the European Economic Area (EEA), along with Iceland and Liechtenstein. It sets its own trade policy, but contributes to the EU budget and takes part in the single market’s free movement of people, goods, services and capital in exchange for compliance with almost all EU rules, on which it cannot vote. Should the UK decide to leave, it seems unlikely that it will then decide to secure only partial freedom on trade at the expense of submitting to regulation it cannot influence.

Other models include Switzerland, which is part of the European Free Trade Association with the EEA countries and has FTAs – more than 120 of them– with the EU on subjects of interest. The UK could also replicate what Turkey has done and join a customs union with the EU, sign a multitude of FTAs, or trade under World Trade Organisation rules, thereby avoiding any negotiation or special agreement with the EU.

However, none of these models would affect financial services because none, aside from the Norwegian model, would provide passporting rights, according to Phillip Souta, head of UK public policy at law firm Clifford Chance. Indeed, should the UK attempt to expand the scope of FTAs to financial services, the so-called ‘prudential carve out’ clause – which allows a country to restrict the provision of financial services in its jurisdiction – would get in the way.

Even under the more generous FTAs such as that between the EU and South Korea, enacted in 2011 and the first to lower further tariff barriers, countries retain the right to protect banking and financial services clients as they see fit. The EU-South Korea FTA’s prudential carve out reads: “Not withstanding any other provisions of the agreement, a member shall not be prevented from taking measures for prudential reasons including for the protection of investors, depositors, policy holders or persons to whom a fiduciary duty is owed by a financial services supplier, all to insure the integrity and stability of the financial system.”

Legal equivalence

The UK could decide to seek access to the single market through the equivalence regime included in a number of the EU financial services regulations. This, however, would mean that British legislation would need to be recognised as equal to the European law, denting the new-found regulatory freedom in exchange for access to the single market. Equivalence would have to be proven and agreed upon in yet another round of time-consuming state negotiations.

Mr Hill knows this from experience. “I recently had to do an equivalence agreement on clearing houses between the EU and the US, and both the US and I wanted to do the deal quickly. That took us just under four years,” he says. “And that’s just one very important but specific subset of financial services. There is no reason to think that other countries that have their own priorities will want to invest their political capital in constructing rules and approaches that would suit the City of London.”

The potentially acrimonious nature of a UK-EU break-up might complicate things further, adds Mr Grand. “From a negotiation point of view, if the EU wanted to punish the UK because member states felt we had behaved so badly and so disloyally towards Europe, then financial services would be a very easy way of doing it,” he says. “You don’t have to change anything in EU law to make it very hard for UK businesses to continue to sell their services to the region.”

Notice period

Brexit supporters play down the importance of passporting. Gerald Lyons, economic adviser to former London mayor Boris Johnson, has long voiced his concerns over the EU. In an Economists for Brexit paper, he says that the reality of passporting is less trouble free than the theory behind it would suggest, especially in retail banking, where lenders often feel the need to set up local presences, rather than selling services from headquarters. He adds that, crucially, the UK's ability to influence regulation coming out of Brussels has weakened, in particular surrounding rules on bank bonuses, the financial transaction tax and the ban on short-selling.

Nicolas Mackel, chief executive at development agency Luxembourg for Finance, believes the passporting of investment funds under Ucits also could be improved, though he sees great value in the UK's membership of the EU, despite the fact that some believe Luxembourg could be a big winner of investment fund and debt listings business in the event of a Brexit.

To exit the EU, a member state is required to serve notice under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which provides for a period of two years to negotiate divorce terms: a relatively tight timeframe. An extension may be granted, but should the British people vote to leave and no agreement is reached before the deadline, the results could be catastrophic, says Mr Grand. “[In the absence of] some form of agreed extension [a UK firm] would simply have to move or cease trading in the EU. You’d have no authorisation to continue offering financial services within the EU based on your UK permissions,” he says.

See you in court

Another option being mooted would entail passing an EU continuity law that subsumes all directly applicable laws into English law, without serving notice under Article 50. This means that the UK would not formally cease to be a member of the EU, but it would start amending EU law as it applies within the UK, restricting, say, freedom of movement and therefore immigration. EU citizens or businesses that were prejudiced or suffered a loss as a result of the UK breach could lodge claims against the country in the European Court of Justice.

The longer that process goes on, the more the UK builds up a backlog of damages claims against it which would eventually have to be settled as part of exit negotiations, according to Mr Grand. While this option gives the UK leverage and time, concerns have been raised about the damage it may do to the country’s reputation as an international trading partner.

Irritation at EU rule brings critics together. But even outside Brussels’ jurisdiction, UK financial services regulation is unlikely to take a more permissive route while the failures exposed by the financial crisis are still fresh in the public’s memory. Indeed, the UK has tightened its banking requirements to protect depositors and taxpayers since 2008, imposing, for example, tougher liquidity rules on banks, something that has prompted Chinese lenders to move part of their European divisions to Luxembourg in 2012. Separation between retail and investment banking divisions, the so-called ringfencing rule that will become applicable in 2019, is also a UK peculiarity.

Privately, a number of bankers dismiss Brexit as a low-probability event: the broad consensus within their organisations is that things will remain as they are. Kallum Pickering, a senior UK economist at Berenberg, agrees. He notes that British voters tend to be very pragmatic when it comes to issues that may have big economic consequences.

As for the vote itself, bankers, politicians and CEOs will be keenly watching the polls in its final few weeks. Control over national borders will always make bigger headlines than percentage changes to gross domestic product, though frustrations over what the EU is perceived as doing or not doing about either issue may spiral. Europe’s own account of the relationship with the UK is also revealing. “The UK is seen by many people in Brussels as an undecided country that, since it joined over 40 years ago, repeatedly had an uneasy relation with the EU,” says Guntram Wolff, a director of think-tank Bruegel.

Perhaps the UK and Europe have grown increasingly uncomfortable in their partnership. But a break-up might not guarantee a brighter future for either. The UK has been a positive, pro-competition influence on the region; while, although sometimes awkwardly, the EU has unified an incredibly large market to the benefit of the UK. The City of London has flourished while part of the EU. It is not apparent how it would continue to do so away from it.