Caught up in European regulation, Germany’s public banks are trying to adapt to new challenges. Across all three banking pillars in the country, financial institutions are particularly struggling with increased competition in retail banking and low profitability.

There are many positives in Germany at the moment. Gross domestic product grew 2.5% in 2013, the unemployment rate is hovering around 5% and exports are strong. The country’s centuries-old banking system, however, is faced with the challenges of low profitability and high competition, and the public banks in particular are feeling pressure from international reforms.

Editor's choice

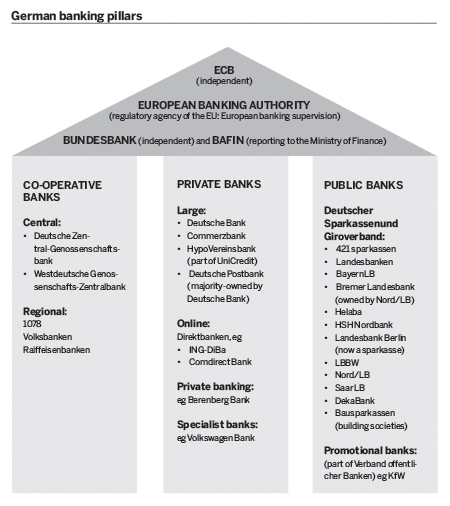

The public banks, the third of Germany’s three-pillared system, mainly consist of the 'sparkassen', the regional savings banks, the federal state banks, the so-called 'landesbanken', building societies [bausparkassen] and promotional banks.

Sparkassen test

The country’s 421 sparkassen, whose remit is not to make a profit, but to serve the country’s banking needs, are operating as separate regional institutions across the country and are, together with the landesbanken and bausparkassen, secured through an underlying loss-sharing agreement.

The major challenge for the sparkassen arises from European regulation, which is often unsuitable for the stable business model of regionally oriented banks, according to Georg Fahrenschon, president of the Deutscher Sparkassen-und Giroverband, the German savings banks association.

“Brussels follows the model of internationally active, publicly traded banks and tries to subordinate everything to this supposed ideal,” he says. “In doing so, regionally focused credit institutions, which provide retail clients and medium-sized companies with financial services on a daily basis, are often overlooked, despite being vital stabilisers of the financial markets.”

A major point of contention is the planned European Banking Union (EBU), which would create a single supervisor, resolution mechanism and rulebook for banks in the eurozone. All this would require institutions such as the regional sparkassen to contribute to a resolution fund, despite having their own resolution plans.

From a supervisory perspective, the EBU plans are a positive step towards more transparency and international recognition.

“Taking banking supervision to the European level is increasing confidence in banking sectors and is adding a European dimension,” says Elke Kӧnig, president of federal financial supervisory authority Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistung, or BaFin as it is better known. “It will improve trust between the supervisors in the system, add transparency among all of us and will hopefully take out any existing or perceived national bias in supervision,” she adds.

Landesbanken scrutiny

The landesbanken, meanwhile, saw their business models come under scrutiny after the European Commission successfully fought through an agreement to end government guarantees for German public banks’ liabilities in 2001.

Previously, the landesbanken sector was very uniform, largely with the same rating and business model across Germany, according to Andreas Dombret, member of the executive board at the Deutsche Bundesbank. “We now have a rather fragmented landesbanken scene [with different business models],” he says.

The law to end the government guarantee came into force in 2005, and several financial institutions across the globe have been shaken up in the wake of the 2008 bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. In Germany, financial implications of the crisis came in form of exposures to bad assets held by landesbanken and private banks, but also indirectly through further bank regulation.

European financial institutions had to adhere to Basel II regulations by 2009 but more stringent capital requirements introduced with Basel III required the mostly federal state-owned landesbanken to find new ways to raise more equity and capital.

“We have found a solution that was very important for publicly owned banks in Germany: to get additional Tier 1 capital that does not require a shareholder structure,” says Gunter Dunkel, president of the association of German public banks, Bundesverband Ӧffentlicher Banken (VӦB). “[Contingent convertibles bonds] can now also be written down should the trigger point be reached, rather than converted to equity, leaving the same effect on capital. Still, the future of the landesbanken is challenging and every bank will have to develop their own model to meet their cost of equity.”

Nord/LB's shipping strategy

Nord/LB has found its niche. The bank, which is about 65% owned by the states of Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt and the rest by the respective savings banks and the sparkassen of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, has positioned itself as a regional bank for shipping and aircraft finance, renewable energy, agriculture and real estate, as well as retail banking.

The shipping sector, while a challenging one in recent years, is central to Nord/LB’s strategy. “We reduced the portfolio from €20.1bn to €16.3bn silently but still are in active business because we believe that even with the portfolio under pressure, you can work on improving it,” says Mr Dunkel, who is also the CEO of Nord/LB. “Because of the diversification of our model and the long-term view of our owners, we are very fortunate to be able to make rational decisions about what preserves the value for the bank best and are not forced to move fast.”

Other landesbanken have changed their business model, such as the former landesbank of Berlin, which has sold its capital markets division to DekaBank and transformed the remainder into a sparkasse. West LB sold parts of its assets to Helaba, the landesbank based in Hesse, created service and portfolio management firm Portigon and transferred its bad assets to Erste Abwicklungsanstalt to be wound down.

Stress testing

While the landesbanken, as well as private and co-operative banks, are part of the EU's ongoing asset quality review (AQR) and stress tests, so too are some German promotional banks such as Rentenbank, “even though their business models are not suitable”, says Mr Dunkel, who represents promotional banks through VӦB. “The banks are very concerned about future regulatory requirements and are wondering whether they will get included into regulation that obviously doesn’t fit,” he adds.

Ms Kӧnig is “reasonably optimistic” for the AQR and the baseline scenario of the upcoming stress tests. The adverse scenario might be challenging for some banks depending on the defined scenarios.

This year’s stress tests are more detailed and extensive than ever. The test covers a period of three years of economic difficulties, which assumes a serious downturn and hike in unemployment, while banks keep lending at the same pace and are not adapting to the economic situation, says Ms Koenig.

Another point, which could prove to be critical for German banks, is the treatment of funds from the European Central Bank’s (ECB's) long-term refinancing operation (LTRO) in the 2014 stress tests, adds Ms Kӧnig. The test allows banks, which still have LTRO money on their books, in an adverse scenario to refinance these funds with cheap money from the ECB (LTROs can be rolled over into main refinancing operations). Meanwhile, institutions that have already repaid the borrowed LTRO money – such as the German banks – would have to replace it with (then more expensive) market funding, a significant disadvantage that German banks are subject to, as Ms Kӧnig points out.

“German banks have stress on both sides of the balance sheet and that is why for some this might be challenging,” she says. “Considering that banks have reasonable capital ratios, assuming that the adverse stress test only asks them to stay a [little] above minimum – 5.5% – that should still be manageable for most [banks].”

The EU’s AQR and stress tests are particularly targeted at the banks that are active in riskier businesses or with more legacy assets. While some public banks can fall into this category, the more typical suspects would be in the second pillar of the German banking system, the one of private banks, dominated by the large institutions of Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank and the UniCredit-owned HypoVereinsbank (HVB).

The private banking model

Deutsche Bank is the largest German bank by assets and Tier 1 capital and one of the few true universal banks globally. It has more than 23 million retail clients in Germany – including those of Postbank, in which it began the process of acquiring a majority stake in 2010 and which accounted for €7.7bn of income in 2013, compared with the €9.6bn of net revenues for the whole of its private and business client franchise, that also includes 5 million international clients. Deutsche's total German business amounted to €11.6bn net revenues in 2013, while its corporate banking and securities business was its most profitable, with €13.6bn of a total €32bn of net revenues for the year.

“We chose this strategy because this is what our clients need and there really is strong demand from our core corporate and institutional client segment for the breadth of reach that a global universal model can bring,” says Christiana Riley, head of corporate strategy at Deutsche Bank.

“We have no illusions of the challenges this part of the industry is facing but we see consolidation around fewer, stronger players, which ultimately plays to our competitive advantage. Within that, we consider our commitment to fixed income – at a time when competitors are exiting this business – a key strategic differentiator and very critical to our long-term proposition to clients.”

Commerzbank and HVB parent UniCredit also have capital markets businesses, but all banks have had to reposition themselves after the crisis.

“German banks have suffered quite a bit from the fallout of the 2008 Lehman Brothers crisis and have taken more than their fair share from it,” says Mr Dombret. “But they have then profited from the macro-economic situation in Germany and started getting rid of their legacy assets. German banks have scaled back on their international businesses, partly due to state aid procedures but also due to a re-evaluation of risk and a reassessment of the banks’ strategies.”

This led to a noticeable reduction of banks’ balance sheets from €5800bn at the end of 2008 to €4100bn at the end of last year, and to a reduction of risk-weighted assets (RWA) from €1700bn to €1100bn for the systemically relevant banks in Germany, according to Mr Dombret, which are also the most active and most international banks.

Deutsche Bank reduced its RWAs from €80bn in 2012 to €48bn by the end of 2013, while Commerzbank, the second largest bank, cut its RWAs from €208bn to €191bn and further lowered them by €3.2bn through the sale of commercial real-estate financing portfolios in Spain and Japan as well as non-performing loans in Portugal in mid-June 2014.

Germany’s co-operatives

Germany's co-operatives, headed by Deutsche Zentral-Genossenschaftsbank (DZ Bank) and Westdeutsche Genossenschafts-Zentralbank, comprise some 1078 institutions that fall under the Volksbanken Raiffeisenbanken brand. These institutions all stand separately, and do not overlap regionally.

DZ Bank, owned by the credit co-operatives, had with $534bn the third largest number of assets in the German market in 2013, behind Deutsche and Commerzbank but ahead of HVB.

In 2013, DZ Bank saw its profits before taxes reach an all-time high of €2.2bn, on the back of reversals on impairment losses on bonds issued by peripheral European states. DZ also increased its lending volume to corporate customers to €26.5bn and saw its customer base among medium and large companies grow by 7%.

Pressure on margins

While not all of the nearly 2000 German banks offer services for retail clients, customers can be choosers in the country. Retail business is competitive and service oriented, giving every client a dedicated advisor in their local branch – apart from the so-called direktbanken, which offer online services, usually at better terms. New business is hard to come by in Germany. In 2012, only 2% of adults did not have an account with a financial institution, according to a World Bank report.

This service orientation and strong concentration puts pressure on banks. “The German banking sector has been benefiting from high asset quality but there is also the downside of a high level of competition, which drives down margins,” says Jan Schildbach, economist at Deutsche Bank. “Banks are trying to adjust to the lower pricing power and higher cost levels than in other countries but so far the German market remains a negative outlier in terms of efficiency and profitability in an international comparison. Not least, there is a need for further consolidation.”

Profitability in the German banking sector is comparatively low, only reaching an average of 4.62% of return on capital in 2013, making the German economy the 10th worst market to be in, according to figures from The Banker Database, while only seven countries had a lower ratio of return on assets.

The low level of returns has been prevalent for years but more stringent capital requirements imposed by the regulators after the Lehman crisis have added an additional constraint on banks.

“Banks have taken on new capital since 2009, which means that return on equity and on capital has been falling – not only because of lower profits but also because of a larger denominator,” says Mr Dombret. “The average return on equity for the 12 largest German banks, between 2009 and 2013, was 4.1%. In 2013 it was 3.9%. This rate is below their cost of equity, so this is not a situation that is perfect over a longer period of time.”

Over the past few years, return on capital excluding foreign-owned subsidiaries among German banks, has changed dramatically. The average return on capital from 2000 to 2008 was 8.74%, while returns from 2009 to 2014 were negative at -0.67%, according to figures from The Banker Database. At the close of 2013, the 4.03% return-on-capital figure was slightly higher than 2012’s 3.99%, but below the 5%-plus recorded in 2010 and 2011.