Business is picking up for Rwanda’s banks following 2013’s slowdown. But competition is becoming more intense as foreign banks increasingly look to enter the fast-growing east African country.

Rwanda’s banks had a tough time in 2013. Growth in the east African economy, which had averaged about 8% since 2000, slowed to 4.6%, its lowest rate in a decade, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Editor's choice

The weakness was caused by donors, who finance about 40% of the Rwandan budget, suspending aid in response to allegations that the government was backing rebels in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo. The fall in foreign exchange inflows was severe enough that the Rwandan franc lost 9% of its value versus the dollar last year, while the decrease in government spending was felt widely.

“The government is a consumer,” says Ephraim Turahirwa, chief executive of Banque Populaire du Rwanda (BPR), the second biggest local bank. “Whenever the government reduces investment and expenditure, it’s felt all over the country.”

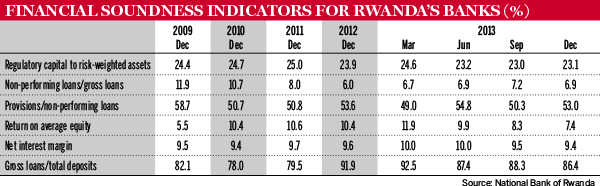

The banking sector was not immune. Non-performing loans (NPLs) rose from 6% at the end of 2012 to 7.2% in September 2013 as companies struggled due to a lack of business from government. Net profits fell 17% in 2013 and the average return on equity dipped to 7.3% from 10.4% a year earlier.

Return to growth

But bankers say the market has since improved thanks to the resumption of aid. The government says gross domestic product is on track to rise at least 6% this year and NPLs had dropped to just over 5% by the end of March. “The situation has been addressed,” says Sanjeev Anand, head of I&M Bank Rwanda, the third largest lender in the country. “The donor flows are back. I see no reason at all for the economy not to recover.”

Amid the renewed buoyancy, many banks are targeting the corporate sector. Although it is highly competitive, bankers say there are plenty of opportunities to lend. Construction is one of the country’s most promising industries. Kigali, the capital, is full of cranes erecting high-rise offices, conference centres and hotels. Telecommunication, tourism and mining projects are attracting plenty of investment, too.

“There are opportunities in all the sectors right now,” says Gilles Guerard, managing director of Ecobank Rwanda, a subsidiary of the Togo-based pan-African lender. “They’re all benefiting from the growth.”

Retail focus

A few banks are focusing more on the retail market, some with the aim of tapping Rwanda's considerable unbanked population. Rather than expanding their branch networks into rural areas to do this, they are using agency banking – whereby they distribute their products via individual roaming agents or outlets such as petrol stations – and mobile banking.

Bank of Kigali, the biggest bank in Rwanda by assets, and I&M recently started offering mVisa, a mobile money service that can be used across different mobile networks and regardless of whether the senders or receivers have bank accounts. “Our big focus is banking the unbanked,” says Mr Anand. “Unlike some other banks, which try to do that by expanding their branch network, our approach is to penetrate the segment electronically. We’re trying to diversify from traditional corporate banking into non-traditional areas that are less competitive.”

As in nearby Kenya, which is home of the mobile phone-based payment service M-Pesa, mobile operators introduced mobile money transfer services to Rwanda. But they had to team up with banks to offer more sophisticated financial products. “The telcos took the lead,” says Mr Guerard. “Now, we’re in partnership with them. They can’t move forward without us.”

Out of the original money transfer platform, Ecobank has developed several ways for its corporate and small business customers to transact through mobile phones. “Corporates are paying salaries via mobile money,” says Mr Guerard. “Shop owners and taxi drivers are taking payments this way.”

Mr Guerard says one of the benefits of mobile banking is that it brings more money into the formal financial system, enabling policy-makers to control levels of liquidity and inflation more easily. “You reduce the amount of cash in circulation,” he says.

John Rwangombwa, Rwanda's central bank governor, adds that mobile banking has helped reduce financial exclusion. The country’s last official survey showed that the number of adult Rwandans with access to formal financial services – including in the microfinance sector – increased from 21% in 2008 to 42% in 2012.

He expects that figure to reach 60% by 2016 because mobile financial services are “growing at a terrific rate”. He says: “There’s been a lot of innovation. People now understand the benefits of working with financial institutions a lot better.”

Foreigners enter

Several foreign lenders have entered Rwanda in the past seven years. Some have taken stakes in existing lenders. Rabobank of the Netherlands acquired 35% of BPR in 2008 and Kenya’s I&M bought Banque Commerciale du Rwanda in 2012, before rebranding it last year.

Ecobank and Nigerian lenders Guaranty Trust Bank and Access Bank each purchased small local lenders, while Atlas Mara, a London-listed cash shell founded by former Barclays chief executive Bob Diamond, agreed in May to buy 77% of the commercial arm of state-owned Development Bank of Rwanda. Others, such as Kenya’s Equity Bank, Kenya Commercial Bank and Crane Bank of Uganda, opted to launch new banks in the country.

Some bankers argue there is a danger of the country becoming overbanked if many more lenders are given licences. They say that with 10 commercial banks, Rwanda already has plenty for a $7.5bn economy. “More and more new banks coming in is neither good for investors nor the industry,” says Mr Anand. “It does not make any sense in my opinion to set up new operations. [If investors want to enter] there are banks here that are available [to buy].”

Others add that there needs to be consolidation in the banking sector. Some believe that the National Bank of Rwanda (NBR), the central bank, will increase the minimum capital requirement for commercial banks from today’s low level of RwFr5bn, equivalent to barely $7m. If so, this could force some small lenders to merge or put themselves up for sale.

Policy-makers are trying to develop the capital markets by encouraging more banks to list. Bank of Kigali, which sold 45% of its shares on the Rwanda Stock Exchange in 2011, is the only one to have launched an initial public offering (IPO). NBR governor Mr Rwangombwa wants others to follow suit. “We hope that in the next two or three years more banks will come to the equity market,” he says. “It would show the maturity of the institutions and reinforce corporate governance.”

Robert Mathu, executive director of Rwanda’s Capital Market Authority, says that banks would not need to change much to go public because they already meet most of the listing requirements. “The banks are the low-hanging fruit,” he says, referring to which companies might list in the next few years. “They report quarterly to the central bank. They are already used to operating in a regulated environment. They have all the structures needed to be public companies.”

High lending rates

Few banks seem set to launch IPOs imminently. But the government is expected to eventually sell its remaining stakes of 30% in Bank of Kigali and 20% in I&M through the public market. “The government will offload its shares [in I&M] at some point,” says Mr Anand. “It will be listed.”

Mr Turahirwa says BPR, a former co-operative whose members now own 65% of the bank, is considering a listing by introduction, whereby shareholders would be able to trade the stock among themselves. “The bank might go fully public later, but we would start with this,” he says.

Rwandan officials would like to see lending rates drop. Although inflation fell from 8% in mid-2012 to 1.4% this June, average interest rates on bank loans have remained about 17%. “Interest rates are a bit high,” says Mr Rwangombwa. “We’ve discussed the cost of lending with the banks. It’s not part of our mandate to regulate interest rates. But we can engage with the banks and promote financial literacy among borrowers, the lack of which at times means they end up borrowing more expensively than they need to.”

For their part, bankers argue that lending rates are justified because the shallowness of the interbank market means they have to be conservative with their lending. “If I run out of liquidity in Rwanda, the opportunities for me to balance my position are very limited,” says Mr Anand. “In Poland, where I worked previously, funds are always available, even if it’s at a certain price.”

The outlook for Rwandan banks seems good. Given the size of the unbanked population and the fast growth of the economy, many will be able to expand their asset bases by 20% or more annually over the medium term.

Yet they have plenty of room for improvement. Their profitability lags that of Kenyan and Ugandan banks, which regularly make returns on equity of more than 20%. Catching up will require plenty of innovation on the part of Rwandan lenders when it comes to launching products and tapping new business areas. This will be especially important if competition increases even further with the expected entry of more foreign lenders into the market.