Karina Robinson argues that, in practical terms, the policies of the Democrats differ little from those of the Republicans. At the end of the day, the US pursues the same strategic objectives regardless of who is in the Oval Office and, moreover, is prepared to go it alone.

‘‘I believe we ought to be trying to build more and more institutional co-operation in the world, while reserving the right to act alone when we have to. They [the Bush administration] have believed, at least for the first three and a half years, that they should act alone whenever they can, using the springboard of what happened on 9/11, and co-operate when they have to. In the end it may bring us to the same place.”

Former President Bill Clinton, interviewed on salon.com

Whether John Kerry moves into the White House or George W Bush remains in power, the differences separating the two parties are minimal. As we approach November’s US elections, the conventional wisdom has it that the unilateralist tag attached to the current administration – albeit one modified by the Iraqi occupation – will be left behind if the Massachusetts Democrat gets into power and inaugurates a new era of multilateralism. Senator Kerry reinforced this by saying earlier this year that he had met with foreign leaders who told him they hoped he would beat Mr Bush because “we need a new [foreign] policy’’.

But America will not change course after the election, whoever wins. Analysts who think that it will have overlooked the realities of the current international order and America’s position in it.

The shock of 9/11, together with a post-Cold War scenario that makes the US the overwhelmingly pre-eminent power – both in economic and military terms – means that even if Mr Kerry wins, the US will continue to go it alone. There may be a difference in tone; but the US will not suddenly become multilateralist.

Unilateral response

Take the unpredictable, but probable, event of another major terrorist attack on US soil. If terrorists had managed to attack the New York Stock Exchange, the International Monetary Fund building in Washington, the Prudential or the Citigroup buildings in New York (the UK is holding eight suspected terrorists of whom two were charged with possessing reconnaissance plans for these targets), is it likely that Mr Bush, or for that matter Mr Kerry, would be on the phone to Nato and other allies to co-ordinate a response? The extreme nature of the circumstances would demand a unilateral response, as they did after 9/11.

It is the first time in decades that pre-election surveys of US voters show them more preoccupied by national security and foreign policy than domestic issues. In response to this, Mr Kerry touted plans in August to add 40,000 troops to the army and to double special forces, indicating that the Democrats will not be soft in the face of international conflict. To tune into the current mood, Mr Kerry has made his participation in the Vietnam War a big selling point.

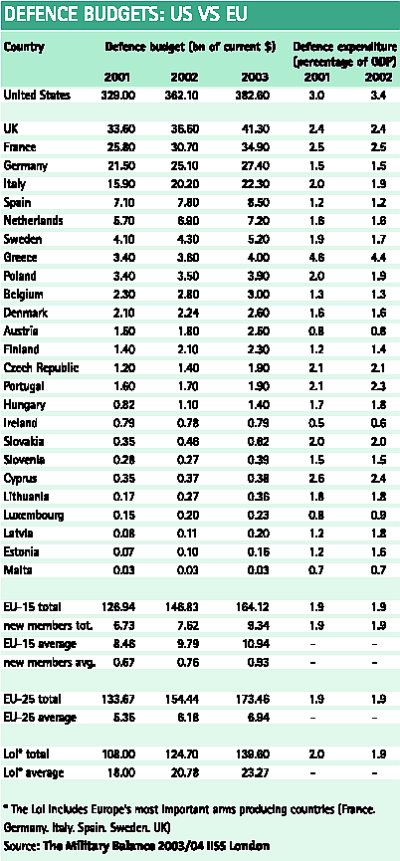

Frustrated by the multilateral process, it’s unlikely that any hard-pressed future administration will be prepared to wait for United Nations’ resolutions that depend, for instance, on the co-operation of France – a permanent member of the Security Council, and a leading opponent of the Iraq war. Neither is the US likely to wait on decisions by Nato or the EU, when the US defence budget is twice that of the combined defence budget of the 25 EU countries.

US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s jibe about Germany and France (in the context of their opposition to the Iraq war) being irrelevant because they represent “old Europe’’ is much more than mere American chutzpah. It reflects the new reality.

As British historian Niall Ferguson points out in his book Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire: “The invasion of Iraq in 2003 was not without a legitimate basis in international law, and was supported in various ways by around 40 other states.’’ This included 18 of the 25 EU countries.

Fluid alliances

Future international coalitions will be put together in a similar ad hoc way, bringing on board those who are supporters at the time, rather than based on historical alliances.

Christopher Coker, professor of international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science, describes this as interest-based multilateralism rather than the value-based multilateralism that existed in the Cold War.

“Multilateralism has become more liquid, partnerships come and go,’’ he says. “Confronted by a unipolar moment, Americans are going to react differently. For the US the defining moment is 9/11 and [it involved] a military solution.”

But America’s increasing use of the military overseas was growing even before 9/11. Between 1945 and 1989, the US military was only used overseas approximately five times. Since 1989 it has been used around 40 times. The US military’s new-found importance, and its enhanced political power, are a result of the new geopolitical order and not solely a response to 9/11. This also means the role is not just a Bush phenomenon but will transfer across different administrations.

The same is true of America’s isolationist stance in non-military areas. Accusations that the current Bush administration is more unilateralist than was Bill Clinton’s government are at best exaggerated, if not entirely untrue. For example, though Mr Bush opposed the International Criminal Court, President Clinton backed it only because he knew it would be unlikely to get through Congress. Mr Clinton’s gesture – both pleasing to foreign powers and costless – is exactly the kind of public relations exercise the current regime avoids. Liberals are irked by this hard line stance but the end result under the Democrats was the same.

Very often the final arbiter of US foreign policy is Congress and the real unilateralists, throughout US history, have generally been found in the Congress, not the White House.

As for the Kyoto Protocol on greenhouse gas emissions, it can be argued that the US economy’s much faster growth in the 1990s would have resulted in the treaty’s costs becoming too onerous under any administration. But with Mr Bush’s pro-business regime and lack of interest in the environment, it was assuredly dead on arrival under his stewardship. For all its jingoism, however, the Bush administration has not always shirked America’s international obligations.

US arrears to the UN have been largely paid back during Mr Bush’s term in office, whereas they were allowed to drag on under Mr Clinton. Similarly on IMF bail-outs and aid flows, Mr Bush has not been as hard line in practice as the rhetoric suggests, leading to further convergence between the Republics and Democrats.

Traditionally, Democrat governments tend to be more protectionist than Republican ones, often forlornly trying to protect American jobs from being wiped out by cheap imports. And Mr Kerry’s rhetoric does sound more protectionist than Mr Bush’s statements.

“It is too glib to say it is just electioneering,’’ argues Jessica Einhorn, dean of the Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies and formerly managing director at the World Bank. “If you pander to factually incorrect prejudice I don’t think you just set that aside after an election.’’

Similarities

But Mr Bush’s record on trade is hardly exemplary and once again there seem to be more similarities between the parties than profound differences. President Bush’s commitment to moving ahead with the World Trade Organisation’s Doha round is relatively recent, and in March 2002 he imposed 30% tariffs on foreign steel. These were dropped in December 2003 only after the tit-for-tat tariffs war looked like getting out of hand.

In terms of the development agenda, the Bush administration took office with some clear ideas, among which was an end to more IMF bail-outs. But the pressure of events soon forced it to go back on its word, with major packages made available for Turkey and Brazil as they ran into difficulties. In other words, Bush-style unilateralism is conducted within pragmatic limits.

Before a 2002 visit to crisis-ridden Brazil, then US Treasury secretary Paul O’Neill famously declared that money heading towards emerging markets was often misappropriated, ending up in “Swiss bank accounts’’. But that same year, Mr Bush launched the Millennium Challenge Account, the largest increase in American foreign aid in decades, although as a percentage of GNP it is still a comparatively tiny 0.15%. Mr Bush also denounced America’s role in nation-building but is now embroiled in just this process in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Strategic priorities

As Ms Einhorn points out: “The single most important long-term issue for the US is to maintain the economic strength and political commitment to lead the international economy.’’ This applies to any US president. Or even “George W Kerry” as Moises Naim, editor of US-based Foreign Policy magazine, calls the next president. He argues that the nature of the world today and the role of the US would force Mr Kerry to adopt Bush-like tactics, while Mr Bush’s second term would be characterised by his adopting some Kerry-like tactics.

When considering the main challenges facing the victor of the November polls, the economy will loom large.

The twin deficits are now a major cause for concern. The budget deficit is running at a record $445bn for the fiscal year 2004 equal to 3.8% of GDP and the current account deficit is over 5% of GDP. Funding the deficit depends on the continuing appetite of East Asian central banks for US Treasury bonds.

On the face of it Mr Kerry should be the more vigilant about bringing the economy back into balance. His advisers include Robert Rubin, who was President Clinton’s Treasury secretary and the foe of high budget deficits. This contrasts with the current administration’s penchant for tax cutting, regardless of whether it’s affordable or not.

Then again, slashing a budget deficit is an awkward task. A Democrat president would be unlikely to cut Medicare or Social Security, the two high-cost programmes, even as extra funds for nation-building and quelling insurrections in Iraq will have to be found. Meanwhile, signs of a slowdown in US growth next year will lower the tax intake and minimise the room for manoeuvre.

Spending latitude

Still, the bottom line is that in 2002 American GDP accounted for just over one-fifth (21.4%) of world output, more than Japan, Germany and Britain combined. Strong economic growth over the past two decades means that as a proportion of GDP, the proportion of funds spent on military matters has decreased, notes Mr Ferguson.

Expenditure on national defence is forecast by the government to remain constant at 3.5% of GDP for three years, compared with an average of 7% during the Cold War. The US could afford to spend considerably more on the military if it wanted to, and this allows it a high degree of unilateralism in its foreign policy. Expect administrations of both colours to take advantage of this latitude in responding to problems in Asia and the Middle East.

Both administrations are also noted for performing considerable U-turns in their foreign policies. With North Korea, for example, it was President Clinton in mid-1994 who strongly considered ordering air strikes on its nuclear installations, although in his second term, in 2000, secretary of state Madeleine Albright travelled to Pyongyang to meet the president, Kim Jong-il. This highlights how policies change and how presidential first terms are not always indicative of second ones.

In 2001, President Bush designated North Korea a member of the “axis of evil’’, along with Iraq and Iran. In 2003 the Bush regime was heading towards a full economic blockade. This year, in July 2004, John Bolton, under-secretary of state for arms control and international security, said the diplomatic approach through the Six-Party Talks (US, North Korea, South Korea, China, Russia and Japan) was the only way forward.

Realities of policy

Mr Kerry said in March that he favoured bilateral talks with North Korea, which he believed was a tougher way of dealing with them, rather than, as one commentator put it, “outsourcing’’ policy in those multilateral talks to China. In fact, the US is tied to working with China, as they are the only ones who can pressure the North Koreans.

With crude oil having approached $50 a barrel and the US mired in post-war Iraq, the Middle East will continue being a priority for an incoming administration. But further intervention looks unlikely.

“The neo-conservatives won’t be as powerful if Mr Bush gets in. They have a particular idea for democracy building in the Middle East and the appetite for it has come and gone,’’ says Jonathan Clarke, foreign affairs scholar at the Cato Institute.

He also believes that although Ms Albright and other members of the Clinton team – who at the time were “idealistic interventionists’’ – are advising Mr Kerry, they have been “conditioned by lessons learned in the past years, so they are a little less ambitious’’.

When it comes to the thorny issue of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, its perennial state of flux makes it difficult to judge. The US is modifying an outdated “road map’’ for peace; the Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, is in the midst of a cabinet revolt over the withdrawal from Gaza; and the Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat, is facing street demonstrations. Allied to the peculiar alliance between the Jewish lobby in the US and the Christian right, and the European inability to bring anything to the table on the Palestinian side, notes the LSE’s Professor Coker, the next administration will be facing an intractable, ever-present tragedy.

As Mr Clinton said of the competing Democrat and Republican policies: “In the end, it may bring us to the same place.’’

He himself is an example of the similarities between the US parties in foreign policy. In 1998 he ordered bombing strikes on Iraqi military targets – arguably a breach of international law – and pledged the elimination of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. He said the US would accomplish the objective alone, if need be.

The Bush administration has seen fit to use a generally less collegiate tone than its predecessor or, potentially, than Mr Kerry. Yet the US, ultimately, is the only member of the UN that can enforce international law.

Its military and economic capabilities are far beyond anything its allies, old or new, can aspire to. Those allies can bring little to the table. A bit of peace-making here or a bit of nation-building there is not enough to return the US to an outdated, Cold War alliance with historic or other allies.

Mr Bush mark two and Mr Kerry are products of a unipolar world order where the threats have changed. In the end, when dealing with any future threats, the US will go it alone, regardless of who is in the Oval Office.