Will you need an office in the future? If so, will it need a chair? The latest indications from online, collaborative, virtual reality games are that your office may not exist in the physical world, so you may not need to be physically present at work. It could all exist in a virtual world, a three-dimensional universe resembling the real thing but without those troublesome physical quirks, such as distance and speed, being barriers to your work’s progress.

If your office does have a physical presence, it might be defined as the IT equipment that you wear, connecting you wirelessly and automatically through keyboards, visual display unit spectacles and earpieces to a network of peers that constitutes your corporation. You could wear your physical office but perceive a virtual office as a real space.

The office can be anything we make it, but history suggests that people are creatures of habit, of the familiar. Although little has changed in the past 100 years of office design, the 21st century offers an entirely new perspective where using space, technology and the global market can give a company the edge.

The past is very much with us, says Mark Rolston, senior vice-president of creative at Frog Design. “If you go back to the turn of the previous century, we had a large room full of clerks or typists working side by side, and eventually you get this concept of corner offices and private space that is the model for building the knowledge worker environment that many of us currently exist in.”

In the 1940s, when George Orwell envisioned a dark futuristic dystopia in his novel 1984, he described the workplace of the future as glittering white office buildings 300 metres high above an urban sprawl, filled with 3000 offices above ground and row upon row of cubicles containing workstations. Each worker has a voice-activated dictation machine and pneumatic tubes for sending notes or parcels across the organisation.

The corporate office of today will probably bear a resemblance to Orwell’s factory-style workplace. This similarity hopefully does not extend to culture. It is simply indicative that, regardless of purpose, the office of the present and the tools in it are based on tried-and-tested methods of process and order, making multiple workers function as a single corporate body.

Reluctance to change

Often businesses are reluctant to accept a change in processes if they are operating within acceptable parameters. The external appearance may change but business processes that work now are rarely experimented with. An example of this can be found at one of the world’s oldest financial services institutions, Lloyds of London, where the brokering and underwriting of insurance are still conducted face to face across wooden desks on the underwriting floor. The irony is that such a practice has remained unchanged for years within an organisation that has moved into what is externally one of the most futuristic looking buildings in the City of London. But where traditional models are under threat in the market, traditional working practices are also liable to change.

In recent years, such straightforward and well-tested layouts are being challenged by innovative designers who are keen to maximise the use of space, gain advantage from every opportunity and even change corporate culture to further strategic aims. In the physical world, increased exposure to ideas and cultures through global business experience lead to innovative new designs that make better use of workspace, helping to improve productivity and innovation.

Creative fields: IDEO designs new space-using concepts

Even some of the simpler concepts, such as hot-desking, are likely to have a lasting impact on the near future, according to Peter Patsalides, managing director at IT and premises consultancy Bailey Teswaine. “These models will deconstruct the office because people invariably will not need to get to a specific place. It works for the staff because travel costs time and money, and it works for the banks because the cost of office, especially in the major financial cities, is phenomenal.”

Revolution?

Claims of radical change are nothing new. At architectural firm KRJD, senior architect Kevin Roche notes that such shifts have been predicted in the business world for years but rarely arrive: “Thirty five years ago, we were talking about the paperless office as we saw the emergence of the computer. The result of the process is that we have more paper now than we had then – with the ease of printing and copying paper you actually have multiple copies of everything.”

In this example, the driver for change – that of computing – overlapped with lots of established practices, leading to the development of both in tandem rather than revolution.

A direct result of the growth in technology usage was the dotcom boom in the late 1990s. With this came radical new business models and, because the businesses themselves had no history, new workplace design. Often driven by the concept of a small group of people using technology to automate the mundane and magnify a company’s reach, they were known for their challenging attitudes to traditional business, often incorporating fun and work into one task. In 2001, the Journal of Real Estate published a paper on the dotcom phenomenon, noting that the working model of the industrial age, that of turning up for work and clocking in, was over. It no longer mattered whether you turned up or not, what mattered was that you worked.

Design impact

Although many of the business models eventually proved unsuccessful, the designs of the dot-com era have had a lasting impact, says Franklin Becker, director of the International Workplace Studies Program (IWSP) and professor in facilities planning and management and human-environment relations at Cornell University in the US. “They had a focus on delivery and this concept has transferred to current business thinking,” he notes. “There was much less focus on rigid control; the time you came in and left was less important than delivery.”

With this in mind, the best minds were sought out and business began looking at facilities and amenities. The culture of working around the clock but with greater freedom than before necessitated a caring environment to encourage and support the workforce.

“They wanted, demanded and got tremendous services ranging from good quality food available any time to the more obvious dry cleaning, banking and anything to make your life easier,” says Mr Becker. “These companies saw little reason to maintain the cubicle way of life.

“Partly this was due to the high growth levels expected, but also there was a need to have collaborative experience. This transfers to current business – for example consulting – where a constant level of change requires high levels of information to manage.”

Although the ‘creative’ side of dotcom culture may not be applicable to other businesses, the need for collaboration is growing more than ever in single offices across the world. Michael Merk at interior design company Steelcase has been exploiting space in offices to drive useful interaction forward, and warns that when looking at change, companies should be careful to evaluate the consequences.

“Even in creative fields there needs to be a balancing act and we saw this in the dotcom boom. There needs to be licence to work on your own,” says Mr Merk.

In organisations that have more rigid structures, the need for interaction and innovation must be measured against the roles that are being played, he says. “We worked with a high-end bank in America and investigated the removal of barriers in the office but found that if you create a more open space, you remove some of the trappings of success for a banker – partly trust – and also that individual’s authority that counts for a lot with the customers of a banker, not only in their own mind.”

As globalisation drives more commoditised jobs away from the central offices and headquarters in both the present and future, this will in turn increase the role of the knowledge worker, argues Mr Merk: “They will be like athletes, demanding the highest quality equipment to deliver on high-performance tasks. Offices will become the cathedrals of the 21st century,” he says.

Unifying culture

Ironically the impact of globalisation has not driven diversity in design but rather uniformity. This is perhaps not too surprising because companies tend toward following best, or if not best then very successful, practice. There are occasions when this trend is challenged by more self-determining cultures, proactively searching for change and improvement.

When Mr Roche designed the headquarters building for Santander Group near Madrid, the bank was trying to unite its workers physically where they had been separated geographically across Madrid and to unite them culturally to retain valued staff. This is telling, says Mr Roche, because the solution was not simply laid at the door of technology.

“They found that you can’t run a corporation from such diverse locations even with modern communications. You can’t get that sense of community that you need, that sense of belonging,” says Mr Roche. As a result, the bank built a campus outside of the city with a full range of amenities and a deliberate accent on working as a group.

“The other solution is to build a high-rise building in town, but that in itself is isolationist because you only tend to meet people on the same floor, or in the toilets or in the lobby. It’s only so many thousand square feet, so the idea of the campus is a very attractive idea,” he says.

What stood the design apart from familiarly impressive, bombastic structures was the focus on the employees of the bank, says Mr Roche. “The Santander design was totally focused on the individuals working there, so there was less interest in providing grandeur for the casual viewer at the expense of the permanent employee. Architecture in its best form can help the human condition by maintaining the sense of community. As human beings, we need to feel some sense of community; we are social animals. A building can help that, while furthering the aims of the bank.”

Using a combination of physical space and the latest systems, Mr Merk helped to orchestrate a positive change at a major IT services provider in Germany, which wanted to improve communications, and reduce costs by permanently relocating people in the organisation and gaining a long-term commitment from employees through establishing a strong work culture. “We asked them: ‘What if we move away from the traditional view that every person has a desk?’ We think the unit of one desk/one person is not working anymore. So why don’t you implement a selective desk policy that makes it possible for people to work wherever they want to while encouraging the blending of the entire business unit?”

More choice for employees

The concept that the IT company developed was based around the employee asking: “Where do I want to work in the office?” Mr Merk says: “The company decided to work on neighbourhoods, where people could land and find their information. To do that, it invested in digitising its archives and the entire paper flow. It can offer employees the opportunity to work from home if they like, including the provision of a workstation and necessary technology. The result has been that 90% of the desks are unassigned and 250 people use 150 desks.

“It is interesting. They view two people working on opposite sides of an empty room as poor communication because you can innovate every time you meet someone.”

As familiarity with technology becomes more developed, Mr Merk believes that this will change the concept of globalisation and comfort with IT-based collaboration. He says: “Globalisation often has the feel that you take one thing and you move it to another country. But with Generation Y individuals, that’s not the way they approach globalisation at all. They feel like they are utterly global sitting at their desks, they expect to be in contact with the rest of the world when they sit down.

“There is fluidity between these people enabled by technology that makes you feel that the promises of globalisation or even just working from home are going to be born out.”

Technology speeds up change

So will the office of the future be a mobile workstation, giving access to a global network of contacts and data? Fred Dust, designer at IDEO, a design-led innovation company, offers wise words from the present: “One thing we have learnt in recent years is how fast technology changes. I see meeting rooms with teleconference screens that are never used, projector screens that are out of date. There is something so wrong about building something with such short lifetime into something with such a long lifetime.”

The most current interactive technologies, grouped under the banner ‘Web 2.0’, are creating opportunities never before thought practical. In Second Life, an online virtual reality built by games provider Linden Labs, almost 400,000 residents exist in a world built of computer code. The economy, based on the Linden dollar that has a real exchange rate with the US dollar, gives residents the ability to profit in the real world from their virtual business.

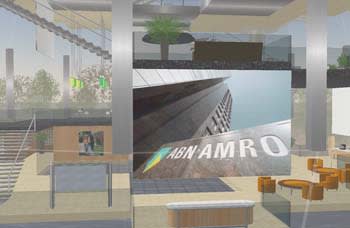

With a reported growth rate of 20% a month for both the population and gross domestic product, it is attracting interest from big business. Reuters has a member of staff reporting from Second Life and ABN AMRO has recently opened an office in the virtual world. What is notable about the world are the familiar trappings – chairs, flowers – that have little practical purpose apart from providing a realistic appearance.

“Virtual realities are a really interesting development because they give people presence,” says Mr Dust. “Technology has traditionally been very poor at representing people; it’s been an interface between two people or businesses, like a teller window. Early science-fiction writers envisioned the internet as a place, not an interface. It was somewhere you could go.”

He stipulates that the way in which we interact via a medium determines our mindset – working on the internet via written word drives people to think like editors – whereas acting in a more ‘realistic’ manner allows natural thought and action. Mr Patsalides believes the old ‘props’ that we currently believe necessary will not seem so permanent “You won’t need a table to hold paper because there will be no need for papers. Even now, I no longer use a meeting table in my office, but rather comfortable furniture with a coffee table for laptops. That fits the requirements for our meetings.”

The likelihood is that all possible opportunities will be taken, says Mr Becker, because choice breeds diversity. “I think there will be more variety in the offices of the future. All of these new developments are not evenly spread across companies. We are not closing some doors and opening others. We’re opening all the doors and letting people have the choice to decide their companies’ future.”Familiar trappings: ABN AMRO’s office in Second Life (below) mimics real life, with buildings, furniture and even flowers.