Few people probably ponder what happens when they click ‘send’ after writing an e-mail? The e-mail travels through the internet, via interconnected ‘highways’ of networks that enable the passage of data. It is picked up by an e-mail service provider such as Google or Yahoo! and the message is sent to one of their data centres. Google, for instance, has eight around the world. There, the e-mail data gets routed to the right address.

As the amount of data created continues to expand thanks to the rise of social networks, conventional telecommunications network bandwidths are at risk of being able to cope with these ever-growing volumes. A solution to this problem emerged a few years ago and has since been gaining in popularity. This solution? The cloud.

Every e-mail needs a home

Cloud computing is not so much a space odyssey as a sombre concoction of enormous data hubs scattered around different parts of the world, usually in countries with cold climates such as Lulea in Sweden (where Facebook has such an operation) or Hamina in Finland (home to most of the data created through Google).

Once an e-mail is sent, for instance, it is filtered for viruses, stored and backed up in the cloud. The likes of Google and Amazon pride themselves on their environmentally friendly and cost- and space-efficient approaches to storing and maintaining data in their clouds. The main drivers for business, however, are flexibility, resilience and outsourcing the responsibility for managing data management processes.

Glen Robinson, a solutions architect at Amazon Web Services (AWS), says: “Instead of buying, owning and maintaining your own data centres or servers, businesses can acquire technology resources such as computing power and storage [as they need them]. The cloud provider manages and maintains the technology infrastructure in a secure environment and users interact with the resources over the internet. By having regions based all over the globe it means customers in the financial services industry can have access to elastic technology resources wherever they are in the world.”

Little wonder, then, that the cloud has been creating a buzz in the financial services sector where data storage and maintenance are as important as ever and institutions are looking for more cost-efficient ways to run their business. But there are some sceptics still, as many institutions fear breaches once the data leaves their hands. This is why many are now moving to hybrid models, in which they choose what kind of data they outsource to public cloud service providers such as Amazon, and what kind of data they prefer to keep in private clouds.

More and more data

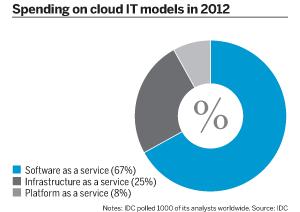

Market research group International Data Corporation estimates that global IT spending will have grown by 6.9% in 2012. In emerging markets it will have risen by an even higher percentage, at 13.8%. Spending on public and private cloud services alone will top $60bn. About 25% of the spend will be invested in the so-called infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) models, which are the servers or disks for a cloud system. In an IaaS model, the user runs the software and data in house. That means every time there is a new version of the cloud system, the user will have to make sure they upgrade it.

About 8% of cloud services' adoption budgets will be spent on the platform-as-a-service model, which is the IaaS plus the platform. In these models, whenever there is a new version of the cloud system, the user does not need to upgrade it themselves, but the cloud service provider will take the responsibility. The majority (67%) of the cloud service management spend will go to software-as-a-service (SaaS) models, the most familiar form of cloud services available. SaaS models comprise the infrastructure and platforms of the cloud, as well as any other software. Management consulting firm AT Kearney expects 80% of Fortune 1000 companies to use cloud services in 2013, one-fifth of which will not have any hardware for the cloud system.

Andy Evans, CEO of cloud computing company Xactium, says a cloud service is ideal for financial institutions reacting to regulatory change such as Basel III and Sarbanes-Oxley because of its great speed. “One of our customers said it would take up to five years to fully implement a working cloud governance, risk and management solution if they were to create it in house,” he says.

Cloud sceptics

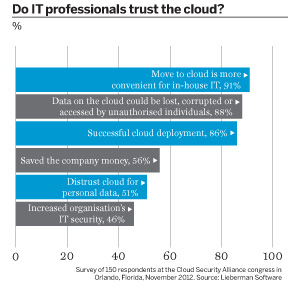

There are sceptics of course, even among CIOs that use cloud services in their professional environment. More than half of IT experts with a job focus on the cloud do not trust the cloud with their own personal data, according to a survey by Lieberman Software. Some 90% do not trust the cloud with sensitive data from their organisation and prefer to keep this information in a so-called private, or internal, cloud.

This scepticism is not helped by the lack of cloud-specific regulation. There have been common certifications and accreditations that are considered a prerequisite for cloud providers, but now there are moves towards introducing stronger legislation. In August, the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) and the British Standards Institution (BSI) proposed a “flexible, three-stage scheme” based on the CSA’s security guidance and control objectives to spur trust and transparency in cloud services.

The three stages consist of a self-assessment form that is submitted to the CSA to prove that a cloud services provider meets the CSA’s best practice guidelines, an assessment form from an independent third-party, and a continuous monitoring-based certification that will be run by both the BSI and CSA, which is still in development.

As things stand at present, the responsibility for looking after data remains with the data controller, ie. the cloud customer. This means if a bank outsources something as major as data, it must do careful due diligence into the supplier, the supplier’s security systems and carry out regular audits of these things, says John Halton, a partner at law firm Cripps Harries Hall.

“As a bare minimum, you have to have an extremely robust contract laying out their obligations for keeping the data secure. You have to have provisions allowing you to inspect what your cloud supplier is doing and you actually have to exercise those rights to make sure that you are doing the appropriate due diligence,” he says.

More familiar ground

In other words, cloud adoption tends be in line with traditional IT services that financial institutions are more accustomed to, with their own data centre, a business continuity plan and disaster recovery policy. “Public cloud providers only provide a service ‘credit’ – they do not really give service level agreements [SLA] about data. They hold the data for you. Until we have public providers that have an SLA in place contractually. I doubt we’ll see many enterprises – particularly in the financial markets – moving to the cloud,” says Lynn Collier, senior director for file and content at data storage company Hitachi Data Systems.

But Microsoft’s chief technology officer for cloud services in the UK, Robert Fraser, disagrees with such views. “There is an assumption that public clouds and financial institutions don’t mix,” he says. Yet in the UK, Mitsubishi UFJ Securities has adopted Microsoft’s Windows Azure platform to calculate and provide risk numbers faster, reduce end-of-day hedging costs and provide a model that more tightly couples operational costs with trading activities.

Robert Griffiths, vice-president at Mitsubishi UFJ Securities International, is happy with this hybrid solution, as not all of the company’s data is on the public cloud. “This improves our efficiency because it gives us better insights into business performance and profitability as well as a view into overall day-to-day operations,” he says.

Another happy user is Amazon’s Spanish bank client Bankinter, which managed to improve its average time for running simulations from 23 hours to 20 minutes. The bank estimates that it saved 100 times the expense it would have had to invest in hardware alone by using AWS, according to Mr Robinson.

Amazonian strength

Cloud supporters argue that such a service can help break down the silo barriers in institutions as it can provide a central database. The key issue that many financial institutions have is that they use a large set of computational resources to do number crunching for pricing calculations, says Mr Fraser at Microsoft. This is capital-intensive and beyond the reach of more and more financial institutions. Mr Fraser says one option is to do the minimum amount of processing to meet regulatory requirements and internal controls, and outsource the rest of the workload. Thus, the cloud offers much greater depth to the user’s computational capacity.

To enable customers to retain their data, Amazon built a storage service – Amazon S3 – “for 99.999999999% durability” over a given year, says Mr Robinson. “We store multiple copies of each object across multiple locations within the same geographic region by default and at no additional charge," he says. "So if you store 10,000 objects with Amazon S3, you can, on average, expect to incur a loss of a single object once every 10 million years. Amazon S3 is designed to sustain the concurrent loss of data in two facilities. To help with data retention, we also have a versioning feature that allows customers to revert to the last version of any object they unintentionally delete or somehow lose due to application failure.”

Last year, Amazon also introduced Glacier, “an extremely low-cost storage service that provides secure and durable storage for data archiving and back-up”, says Mr Robinson. This service is low-cost and charges $0.01 per gigabyte per month. Apple’s iPod Classic, for instance, comes with 160 gigabyte storage that has enough room for 40,000 songs, 200 hours of video and 25,000 photos. To put that much on Amazon’s Glacier would cost $1.60 per month. But to possess 25,000 photos, a 40-year-old would have had to have taken 13 pictures every week since birth. So in this example, the cost of the cloud would be lower than $1.60 because users only pay for the data and time they use. Unlike with in-house data centres, there are no risks of overpaying for extra storage capacity.

What if?

But what if a disaster struck the data centre? Or the data got lost somehow? “Cloud service providers have at least two or three data centres that are geographically separated, so even if a meteoroid hit one of the locations, you would still have the data elsewhere," says Mr Halton at Cripps Harries Hall. "This is already common practise. It is a key issue for the IT people within financial institutions – they make sure that redundancy is built-in. Otherwise you would have a real problem.”

Amazon’s AWS for instance has tools and features for customers to help them create resilient and available applications and infrastructures. Each of the regions where the AWS infrastructure is located consists of what Mr Robinson describes as 'availability zones' (AZs), made up of one or more data centres.

“AZs are distinct locations that are engineered to be insulated from failures in other AZs and provide inexpensive, low-latency network connectivity to other AZs in the same region. For example AZs are each on different tier-one networks, different electricity grids, different flood plains and different seismic zones. If one AZ were to fall off the face of the earth, all other AZs in the same region would still operate seamlessly. This gives customers the opportunity to architect their applications across multiple AZs in the same region to build highly available and resilient applications and infrastructures.”

This approach has been so successful among AWS's customers that one of them, on-demand internet streaming media provider Netflix, used Amazon’s tools and then built a program based on Amazon’s tools, called Chaos Monkey, which is designed to purposely cause failure in order to increase the resiliency of their applications. It randomly disables parts of the technology infrastructure to make sure it can survive common types of failure without any customer impact, says Mr Robinson. “The goal is to have a system so resilient that a failure at 3am on a Sunday will not even be noticed,” he adds. Netflix has now open-sourced this tool to other enterprises.

A greener approach

There is another, undeniable, advantage of the cloud, and that is how environmentally friendly it is. Back in 2007, IT accounted for 2% of the global carbon footprint, according to calculations by McKinsey. By 2020, this will have doubled.

Data centres use a lot of energy because they run non-stop and have to be kept cool to prevent the machines from overheating, which is why many are located in colder climates. But as more companies move at least part their workflow to the cloud, propriety data centres will use much less energy, thus cutting back the overall carbon footprint.

Google, for example, prides itself on the fact that it uses less energy than what the company refers to as a “typical data centre”. It buys green power from wind farms near its data centres and provides investment for new wind projects. On a website dedicated to its green ambitions, Google explains that another tactic is keeping the temperature on the server floors at 27 degrees Celsius, so that “we don’t need as much energy-intensive air-conditioning, and our employees get to wear shorts to work”.