Europe’s new corporate funding landscape

The eurozone crisis has led to a surge in corporate bond issuance among European companies as they look to diversify from bank funding. But the relationship between banks and corporate clients has scarcely weakened. In some ways, it might even have strengthened.

When Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP Billiton attempted an audacious $150bn takeover of its main rival Rio Tinto in late 2007, getting financing for the deal was virtually an afterthought. Despite BHP wanting a huge debt package to fund the bid, which it would back away from a year later as the global economy slumped, it had no doubt it could count on its relationship banks to stump up the cash. One capital markets banker close to BHP says a group of just seven lenders had agreed to underwrite a $55bn loan barely 12 hours after the company put in its first calls to them.

Editor's choice

More on European capital markets

More on European corporate issuers

Sadly for corporate borrowers, those days are gone. While most large-cap European companies are still able to get merger and acquisition (M&A) funding from their banks, the process is more complicated and requires them to address the issue at a far earlier stage.

“Between 2003 and 2006, liquidity was everywhere and nobody worried about its availability,” says Ingrid Hengster, Royal Bank of Scotland's (RBS's) country head for Germany, Austria and Switzerland. “Corporates were used to focusing almost solely on how to make an M&A deal happen rather than on the financing. That’s completely changed. These days, financing is discussed very early on when someone plans an acquisition.”

Since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, Europe’s corporate funding landscape has changed considerably, and not just for M&A transactions. With few exceptions, the leading banks on the continent have had to focus on deleveraging and shedding risk-weighted assets to bolster their capital ratios and comply with new regulations. Although they have not ceased using their balance sheets to support corporate clients, particularly investment-grade ones, they are much warier about providing long-term tenors. For acquisitions, borrowers are typically only offered short-term loans of one to two years that need to be refinanced quickly, usually via the bond or equity markets.

Ancillary business

Banks are also more explicit about the ancillary business they want from clients in return for their credit lines. Although Europe’s lenders have long used their funding as a way of capturing more profitable business from borrowers – corporate loans are often priced below banks’ own cost of capital – they now exert far more pressure on clients to ensure that they are given future bond or derivatives mandates.

“Whenever liquidity and capital are deployed, the return has to be very clearly codified,” says Christopher Marks, global head of debt capital markets at BNP Paribas. “It used to be that we talked of relationships or franchises – soft terms that justified a variety of expenditures. Things are now much more tangible. You lend and you want deals and money in the course of the following 18 months.

“Things are very explicit. The money is too expensive for that not to be the case.”

The absence of long-term bank funding has led to a major increase in corporate bond issuance in Europe. Unlike in the US, where big companies use the capital markets for about 80% of their funding, European firms have traditionally been far more reliant on banks. Yet that is changing. The trend, dubbed ‘disintermediation’ by bankers, began in 2009, the year after Lehman Brothers collapsed. Europe’s investment-grade companies, worried about the plight of their relationship banks, rushed to find alternative sources of funding and issued a record $585bn of bonds, according to Dealogic, a capital markets data provider.

Volumes dipped in 2010 and 2011, largely because most companies had completed the bulk of their refinancing requirements. But they picked up again in 2012, with almost $500bn of high-grade corporate bonds sold in Europe. Syndicated loan volumes on the continent, meanwhile, fell to their lowest level since 2003. “In Europe, new financing is coming from the capital markets,” says John Grout, policy and technical director at the UK’s Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT), an industry body.

No complaints

Banks have largely welcomed the shift in funding patterns. Their syndicated loans teams may be struggling amid a lack of business, but the extra activity in the capital markets has given them the opportunity to win lucrative bond mandates without having to deploy their balance sheets. Bankers claim that borrowers are happy, too.

“The feedback I get from issuers is very positive,” says Ms Hengster. “I haven’t had any say: ‘This is too costly. It didn’t make sense for us.’ All the clients say they would do it again. Bond funding gives them access to new investors and often longer tenors. It gives them a flexibility which they otherwise might not have.”

Borrowers have been helped by the sheer scale of demand for their bonds. With interest rates on sovereign bonds in much of Europe, particularly the northern part, so low, investors have scrambled to take advantage of the extra yield offered by corporate deals. And it is not just companies from Europe’s strongest economies that have benefitted. Those from Spain, Portugal and Italy have seen heavy demand for their bonds in the past year. Spain’s Repsol, an oil and gas company, issued a €1.2bn seven-year note with a yield of just 2.72% in May, the lowest interest rate paid by a Spanish company since the launch of the euro.

“The low interest rate environment has been very favourable,” says Philippe Ferreira, an analyst at Société Générale. “Corporate borrowers have taken advantage of this and the demand for their bonds is huge. Last year we saw corporate bond spreads tightening as we have never seen in the past.”

Borrowers are becoming increasingly innovative with their funding in the capital markets. Instead of just issuing public vanilla bonds in their home currency, they are tapping private placement markets, particularly in the US, selling deals in a range of currencies, including Asian ones, and even raising hybrid bonds, equity-like instruments that help bolster their credit ratings due to their long-term, and sometimes even perpetual, tenors. Between January and March this year, Europe’s companies issued a record number of hybrid bonds for a quarterly period. French utility EDF was the most prominent borrower, printing a €4bn maiden perpetual deal in January.

Bankers say the ever more diverse range of issuance by European firms demonstrates that, unlike a decade ago, they no longer view the capital markets with trepidation and are fully aware of what they can offer. “European corporates know what all the different capital market instruments are,” says Roman Schmidt, global head of corporate finance at Commerzbank. “There’s no need to educate them anymore. For them, it’s really a story about where they get the cheapest funding.”

80:20 on the way?

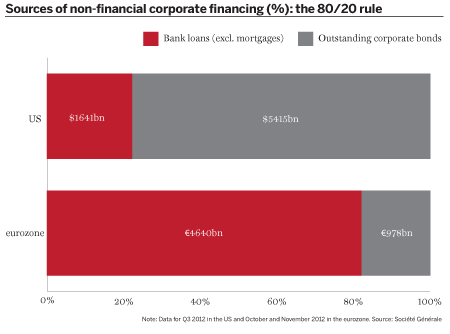

How far will the process of disintermediation go? Recent research by Société Générale stated that, as of late 2012, outstanding debt securities issued by non-financial companies in the euro area totalled roughly €1000bn, while there were €4600bn of corporate loans. Most bankers and analysts say this ratio will become more weighted towards bonds in the next few years, but that the so-called ‘80:20 model’ seen in the US will not be replicated in Europe.

“Europe will not get to where the US is and have an almost fully disintermediated financing model,” says Mr Ferreira. “In Europe, the role of banks is routed in history. But it is gradually evolving as a result of tighter bank regulations. In 10 or 20 years, we could see a 40:60 split in favour of bank funding.”

Others add that politicians in countries such as Germany would resist any shift that severely lessened the importance of banking funding. Many are wary of capital markets and view banks as a crucial tool for fulfilling their economic policies. “On mainland Europe, there’s still a strong distrust of markets,” says BNP's Mr Marks. “The language deployed by politicians often harks back to a lexicon of three decades ago. You see that revealed in some policy measures, such as the ban on shorting. There’s a sense you can control the market.

“Policy-makers aren’t under any illusion that if you roll back the breadth of the banking sector, you lose a lot of your controlled drivers of economic activity.”

As such, the rise of bond funding by no means signals the death of Europe’s syndicated loan market. In any case, loans remain a crucial anchor product for banks to lure more profitable business from clients, not least bond mandates. The value banks attach to providing funding to blue-chip companies is reflected by the fact margins on their syndicated loans remain razor-thin, despite the eurozone crisis.

One senior European corporate banker likens loans to milk in supermarkets. “The supermarkets don’t make money from milk,” he says. “But they have to offer it otherwise nobody would shop with them. They just hope that once the customer is there he will be tempted also to buy expensive bottles of wine.

“It’s similar when it comes to banking. If the anchor product leads to the client trying another product, then that’s the ideal relationship.”

Strong bonds

It is for this reason that European banks say their relations with corporate clients remain as strong as in the pre-crisis era, when bond issuance had yet to take off. Blue-chip firms still regularly raise syndicated loans, especially undrawn backstop lines, which help boost their ratings and cannot be raised in the capital markets.

Moreover, companies need banks to help them enter the bond market. Despite demand for corporate bonds being so high, bankers dismiss the idea that borrowers could tap the market on their own. “There are always discussions about whether corporates could issue bonds without using banks as intermediaries,” says Ms Hengster of RBS. “But I haven’t seen it yet. It wouldn’t make sense for clients because they would have to build their own infrastructure, which would make it more complex for them than going via banks.”

Bankers almost universally think that disintermediation will continue in Europe for the next few years. Even with companies still using loans and the US model unlikely to be replicated, they believe bond issuance will increase as a proportion of overall corporate funding. “In the long-term, companies that have used the bond market will tend to come back to it,” says Commerzbank’s Mr Schmidt. “It gives them relatively long-term funding. And corporate bonds are easy to execute these days.”

Analysts also doubt that the popularity of European corporate bonds is a temporary phenomenon caused only by low interest rates. They say investors realise that such deals have performed well and been less volatile than many other types of assets over the past few years. Neither do they believe that demand for companies’ debt will wane if and when sovereign and bank bonds start offering better returns. “I would expect demand to remain, even if interest rates go back up,” says Mr Schmidt.

Pete Hahn, a lecturer at London’s Cass Business School and Citi’s former senior corporate finance officer for the UK, says that a long-term investor base for corporate bonds is more or less ensured because of the growing realisation among Europeans that they can no longer rely on governments to provide for their retirement. “The ultimate driver of change for the EU is that the crisis has exposed how difficult it is for the state to fund pensions,” he says. “That’s going to create an incentive for more and more people to save for their retirement. It will create an investor pool looking for long-term assets and returns.”

Banks sitting happy

Europe’s economic crisis has changed the relationship between big European companies and banks. Most lenders, especially those outside the continent’s southern periphery, no longer face the acute liquidity shortages they experienced in mid-2011. But borrowers have become more aware of the risks of relying too much on banks. The growth in bond issuance is a direct consequence of this.

Another, says the ACT’s Mr Grout, is that many large companies are looking at placing money with some banks via reverse repurchase agreements (repos), rather than as deposits. “Corporates are much more sceptical of banks’ credit standings,” he says. “There are some banks you would love to deposit money with, but which won’t take it from you. And there are some banks that you would rather not deposit with, but which are keen for you to do it. The reverse repo is the way to deal with them. There’s much more concern than action on the repo front. But companies are aware of it.”

Given how the eurozone crisis has demonstrated more clearly than ever the need for companies to have diverse sources of funding, disintermediation among European companies is seemingly an irreversible trend. But for banks operating on the continent that is no depressing thing. Even if corporate borrowers do not take on as many loans as before, they will still need to use banks for the multitude of other financial transactions they make.