Spencer Lake, global head of debt capital markets, HSBC

Last year saw an amazing turnaround for debt capital markets which went from near death in 2008 to rude health in 2009. This year began with another intense round of capital raising, but clouds have appeared on the horizon. Will sovereign debt fears, growing regulatory pressure, inflationary spikes and fears of a double-dip recession put DCM back in hospital? Writer Geraldine Lambe

In November 2008, German car-maker BMW had to pay nearly 9% to get a five-year bond away. By September 2009, it paid only 4% for another five-year offering. This just about sums up the extraordinary recovery of debt capital markets (DCM) in 2009, which turned into a bonanza for banks' DCM businesses. Once the markets recovered from the standstill in the final quarter of 2008, the floodgates opened in 2009 and issuers rushed to market. As spreads came in and credit investor appetite returned, borrowers grabbed the opportunity to de-lever and pre-fund.

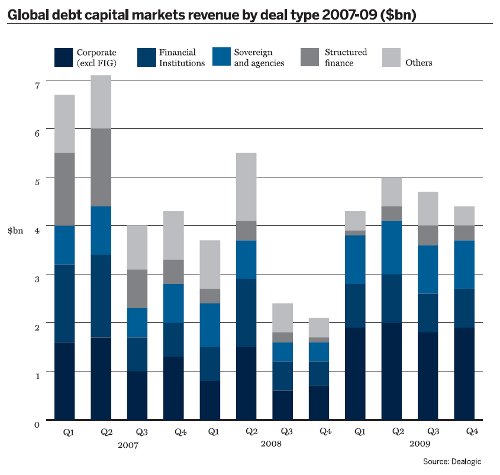

Data from Dealogic shows that total corporate bond volume reached a record $2990bn last year and non-financial issuance surpassed $1500bn for the first time ever. Global corporate investment-grade bond volume - excluding financials - accounted for 23% of total DCM volume, at $1400bn, with issuance from investment-grade corporates in Europe, the Middle East and Africa surpassing that of the Americas region for the first time ever. High-yield bonds had their best year since 2006, with issuance of $178.9bn, up 261% on 2008. Investors profited, with high-yield bonds rising more than 50%, providing their best-ever returns relative to equities.

While most market participants expect debt markets to remain robust in 2010, few believe they will be as busy as last year.

A flying start

Markets got off to a good start in 2010 as fears of an interest rate rise sparked feverish activity in the first week of January. While borrowers traditionally sell bonds in the early part of the year when investors have new funds and to avoid the 'purdah' imposed by earnings announcements, January's spurt of capital raising was particularly intense. In the first 10 days of January alone, more than $75bn was raised - more than two-thirds of which was by financial institutions. The rally in corporate bond markets lowered the interest rate premium to government bonds, pushing some key measures in the credit markets back to where they were two years ago - before the credit market collapse that fuelled the global economic crisis. These conditions pushed issuers to take advantage of a sweet spot in the markets even if they had not planned to raise money until later in the year.

But, as the financial crisis of 2008/09 morphs into the fiscal crisis of 2010, markets are becoming increasingly jittery. Many participants are worried that Western economies will suffer a 'double-dip' recession; others fear that economies will slump again as governments exit quantitative easing.

In January, the cost of insuring against the risk of debt default by European nations rose higher than for top investment-grade companies for the first time ever, as mounting government debt prompted worries about the health of many Western economies. According to figures from data provider Markit, the cost of protecting against the combined risk of default of 15 developed European nations - including Germany, France and the UK - was higher than for the collective risk of Europe's top 125 investment-grade companies.

Sovereign space

It is hard to predict what will happen in the sovereign space. As Greece's debt woes threatened to spill over into the other peripheral eurozone economies, a ripple effect was felt in other markets, pushing the euro down steeply and putting pressure on bonds.

But no sooner had Germany and other eurozone partners indicated that they would lend money to Greece or buy its sovereign bonds should the country's debt-laden government be unable to fund itself in the financial markets, than Portugal - one of the peripheral European countries seen to be dangerously indebted - seized the opportunity, taking €13bn of orders for a €3bn 10-year offering at a lower cost. The positive market sentiment created by support for Greece helped Portugal's five-year bonds to trade in to 320 basis points (bps) over mid-swaps from 360bps the previous day, meaning that Portugal was able to revise pricing on its new issue down to mid-swaps plus 140bps, from the initial range of 145bps to 150bps.

"The sovereign space will be prove to be interesting all year," says Spencer Lake, global head of DCM for HSBC. "There are a number of perceptual and actual challenges to be overcome. In Europe, for example, even with potential support from Germany and/or the EU, on a near-term basis there is quite a bit of financing to get done and work to improve the overall profile of their debt."

Sovereign woes will have a knock-on effect on the banks in indebted countries, where some may find it difficult to raise capital as the sovereign ceiling begins to have an impact. This is already evident in the interbank lending markets. Since the middle of January, Greek banks have been virtually shut out. Lending to the country's four leading banks, National Bank of Greece, EFG Eurobank, Alpha Bank and Piraeus Bank, in Europe's interdealer markets - which generally sees daily volumes of €330bn - has dried to a trickle. The banks are now only able to borrow in the repo markets, which means that they must use government bonds as collateral to raise money. Being frozen out of the unsecured market means that Greek institutions are having to raise money at punitive interest rates through private deals with international banks.

Lending limitations

Globally, banks must also grapple with tougher capital and liquidity requirements, meaning that lending capacity may also be limited. "One of the year's most crucial determinants of debt capital market activity will be whether banks are willing or able to lend," says Martin Egan, global head of syndicate at BNP Paribas.

"Despite last year's record capital raisings, bank balance sheets are still constrained because of increasing regulatory capital requirements. As banks try to work out the best structure and scale for their businesses, there are no guarantees that they will lend to the degree that companies need them to. This will push companies towards the capital markets"

That said, corporates funded pretty aggressively last year and into the beginning of this year, so this may indicate fewer funding requirements anyway. It certainly means that the year began with tight spreads, and this is affecting investor appetite for corporate paper.

"It will be difficult for the market to absorb as much paper as it did last year," says Mr Lake. "To accommodate the needed financing, I suspect spreads will move back out a bit and rates are likely to move higher in order to attract enough [investor] interest."

In the high-yield sector, bankers have been predicting a bumper year as risk appetite returns. Last year, 11% of high-yield companies went into default according to Standard & Poor's, but companies that were left high and dry a year ago are now finding investors clamouring for their debt as investors search for yield. At the same time, private equity-backed businesses have been paying their owners dividends out of new bond issues.

In the week beginning January 11, companies raised $11.7bn in the high-yield bond market, the highest volume in history, according to Thomson Reuters. The previous record, $11.4bn, was set at the height of the credit boom in November 2006.

In recent weeks, however, a more hesitant note has sounded. Speculative-grade corporate bond spreads widened by 35bps in the first week of February, the fourth straight increase and the biggest jump since the week ending August 14 when they expanded 37bps, according to the Bank of America Merrill Lynch US High-Yield Master II Index. The bonds lost 0.62% in February, after rallying 1.52% in January.

Bankers remain cautiously optimistic. One banker says that investors are becoming more discriminating but that deals being done for real companies doing real business will attract interest. "Deals are getting done for the higher-end credits who have a good business reason to raise money," he says.

Growing markets

In the emerging markets, last year chalked up more record issuance, with DCM volume reaching $661.3bn, up 61% compared with 2008. Emerging markets are also expected to generate a lot of DCM business this year.

According to some estimates, companies in China, for example, are believed to have borrowing requirements of $8.8bn in 2010, while companies in Mexico need $11bn. JPMorgan figures suggest that Russian companies borrowed $220bn from banks or by selling bonds between 2006 and 2008. This equates to about 13% of Russia's gross domestic product (GDP). In the United Arab Emirates that figure was $135.6bn (53% of GDP); in Turkey it was $72bn (10% of GDP); and in Kazakhstan companies borrowed $44bn (44% of GDP).

A lot of that debt needs to be rolled over or refinanced. Again, bankers are cautiously optimistic but expect investors to be increasingly careful about where they put their money. "There is a lot of appetite for emerging market debt from the more vibrant economies and the better credits," says BNP Paribas' Mr Egan.

DCM still holds a lot of opportunities for its bankers, but they are certainly not as gung-ho as they were last year. Rumbling sovereign debt crises and fears of a double-dip recession have put paid to that. Moreover, inflationary spikes, the gradual exit from quantitative easing and the threat of rising interest rates - already seen in countries such as Australia - could put an end to the sweet spot for DCM.