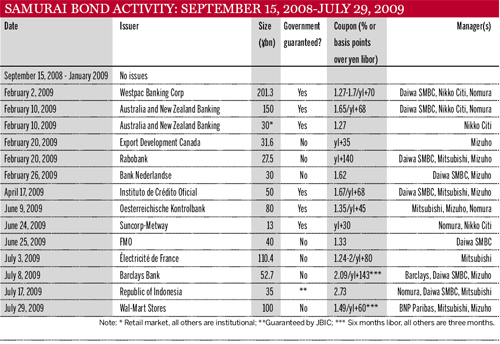

After a five-month standstill following Lehman's collapse last September, activity in Japan's samurai bond market is beginning to pick up and is taking a new direction, breaking the taboo on non-sovereign issues. Writer Charles Smith

Japan's samurai bond market, worth nearly ¥3000bn ($33bn) in the last full year before the Lehman shock traumatised world debt, is coming slowly but surely back to life. Foreign institutions issued ¥445bn-worth of bonds to Japanese investors between February and August this year, following a five-month gap after Lehman's demise in September 2008, when the market was effectively dead.

This is a relief for the five major underwriters (four Japanese and one Japanese-foreign hybrid) that dominate most samurai bond underwriting, leaving little for foreign securities firms such as Barclays Capital and BNP Paribas (which was one of the lead underwriters in an offering brought to the market in July by Wal-Mart, the US retailing giant), but there is still a long way to go for the market to recover its former glory.

Japanese institutions ruled out investment in foreign yen-denominated bond issues after the Lehman collapse. They began having second thoughts in spring this year when the recovery of Japan's own domestic corporate bond market gave them a chance to compare low Japanese coupon rates with higher rates available from non-Japanese issuers outside Japan, says Hajime Suwa, managing director at the debt capital marketing division at Mitsubishi UFJ Securities.

Tetsuo Ishihara, senior analyst for international credit markets at Mizuho Securities, puts a slightly different slant on the market's recovery. The domestic bond market had been stagnating until early 2009, so investors could not get what they wanted at home and eventually turned to samurais, he says. By early 2009, "investors had their mouths open".

While their emphasis differs, both Mr Ishihara and Mr Suwa say that thirsty investors were not the only influence that brought the samurai market back from the dead. It is clear that underwriters have carefully orchestrated the kinds of issues they have brought to market, gradually widening the range of offerings and increasing the risk-return ratio to tempt ultra-cautious buyers.

Rekindling the industry

The first issue to debut in early February after the five-month break was a government-guaranteed ¥200bn offering by Australia's Westpac Banking Corp, one of four big Australian banks which had tapped into the samurai market during the year before the financial crisis. The first Westpac issue did not carry a government guarantee, but it was virtually given sovereign status in February by a set of terms and conditions which put the economic credentials of the Australian government on the line as well as Westpac's own AA rating.

"We made a lot of effort to explain to investors exactly how the government guarantee would work," says Naoyuki Takashina, head of international debt capital markets at Nomura Securities. "Institutional investors came up with all kinds of questions, such as how many days they would have to wait to receive payment from the guarantor, ie: the government, in the event of a default."

The effort paid off, however. The Westpac issue was followed quickly, on February 10, by a similar ¥150bn government-guaranteed offering to institutional investors from Australia New Zealand Banking (ANZ), underwritten by the same team of Daiwa Securities SMBC (an investment banking partnership between Daiwa Securities Group and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group), Nikko Citi and Nomura. The ANZ offering also included a ¥30bn tranche aimed at retail investors that was managed solely by Nikko Citi.

Up a gear

After the first two government-guaranteed issues, underwriters came out with a string of offerings by sovereign supranational agencies (SSA) issuers. The list included Export Development Canada, Austria's Oestereichische Kontrolbank and Spain's Instituto de Crédito Oficial. Tucked away in this list was a ¥35bn issue by Indonesia that was baited with a 95% guarantee from the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JABIC).

An arm of Japan's only surviving state-owned bank, the Japan Finance Corporation, JABIC's role was to boost Indonesia's credit rating from BB- to the required AAA status that could attract investors. The issue was small (¥35bn) because of Indonesia's own cautious approach to the market. JABIC has also signed a memorandum of understanding with the Philippines to guarantee a similar samurai issue some time in the next six to 12 months.

The first crucial step away from government-guaranteed offerings by private financial institutions, or effectively sovereign issues, happened on February 10 when three underwriters, Mitsubishi UFJ, Mizuho and Daiwa SMBC, successfully floated a ¥27.5bn issue by Rabobank, a Dutch specialist in food and agricultural financing. The secret was partly timing. Spreads on government bonds had been squeezed in previous issues, in part because of high costs of transferring the yen borrowed by issuers into dollars or euros.

The Rabo issue offered a spread of 140 basis points (bps) over yen libor - double the 68bps offered by the government-guaranteed ANZ issue of mid-February. Investors went for it and reaped the benefits. "You couldn't get those kind of terms today," says a vice-president for syndicated issues at one of the three underwriters.

Setting a precedent

After Rabo had broken the taboo on effectively non-sovereign issues, the market took off. In early July, Électricité de France (EDF) became the first non-financial corporate issuer in the post-crisis market, raising ¥110.4bn. "That sounds good", says an underwriter at one of the big four Japanese firms, "but investors love the stability of utilities and the dominant shareholder in EDF is, anyway, the French government."

Next came Barclays Bank, billed as the first investment bank to tap into the market, with a ¥52.7bn issue that offered a generous spread, 143bps over yen libor. Finally, Wal-Mart became the first non-financial US corporation to tap into the market when it floated a ¥100bn issue in the final week of July.

Wal-Mart had successfully tapped into the samurai market before the crisis and is seen by Japanese investors as almost a family member as it owns Seiyu Stores, the fourth largest Japanese superstore chain. Wal-Mart's relationship with Seiyu means that the proceeds of its issue are likely to stay in yen. In that way, the issue differs from almost all others before and after the financial crisis, whose proceeds have been routinely swapped into other currencies.

A way to go

The market's recovery since February may seem to have proceeded almost without a hitch, but the range of issues that will tempt investors is still limited. "It is always difficult to predict if or when the samurai market will get back to the pre-crisis level [which was] ¥2300bn-worth of issues in 2008," says Nomura's Mr Takashina. Quite apart from investors' caution, he sees two reasons for not expecting too much. One is that the decline of US investment banks as issuers means there is a need for new kinds of borrowers. Investment banks are not expected to return to the market on the same scale as before, because of changes in their business models.

Some of Mr Takashina's contemporaries believe that this is slightly too cautious. "Banks that survive will borrow again in the future," says Koh Kawana, head of the non-Japan debt syndicates department at Daiwa Securities SMBC. However, the era of large-scale borrowing by banks may be over. The US holds 42% outstanding samurai issues and banks account for 40% of issues, says Mizuho's Mr Ishihara. "Massive deleveraging means that banks will borrow less, so as far as the samurai market is concerned, the pie has become smaller," he says.

Changing market

Mr Ishihara also forecasts structural change in the market, with SSAs and A rated sovereign borrowers playing a more prominent role than before the crisis. In the corporate sector, cautious Japanese investors may also prefer issues by top-rated foreign borrowers to domestic issues by less distinguished Japanese companies.

Mr Takashina expects that future samurai growth will also depend on the cost of swapping yen proceeds into dollars, which is an integral part of the samurai issuance process for dollar-based borrowers. The cross-country basis swap market, which borrowers use to switch out of yen, protects them against currency risk over the standard five-year term of a bond, but is highly priced and has fluctuated widely since the market was relaunched in February.

Last August, the market had reached a point where, for any given issue, the spread paid by the borrowers after conversion into dollars was 37bps higher over US libor than the pre-conversion rate over yen libor. That figure was much higher in February and March, and could rise higher again.

Niche appeal

A related problem is that a samurai issue takes time to arrange, often as much as three or four months for a standalone issue which is not supported by 'shelf registration', a system for advance clearance of legal hurdles. "If the basis swap moves significantly against us before pricing, the efficacy of the overall offer comes into question," says Duncan Phillips, vice-president for debt syndication at Nikko Citi's capital markets origination department.

The complications and costs of preparing a samurai issue are two reasons for the popularity of the euro-yen market, where issuers float yen-denominated bonds using the legal framework of countries other than Japan (usually the UK). Euro-yen issues took off in the 1970s when non-Japanese investors wanted exposure to the yen which they could not obtain by buying Japanese government bonds, because Japan's Ministry of Finance systematically discouraged foreign investment in them.

Japan's Ministry of Finance now encourages foreigners to buy government bonds and the yen is less popular anyway as a global currency, so investors in euro-yen issues are almost always Japanese institutional investors, although Hong Kong and Singapore investors occasionally invest too.

As euro-yen issues take much less time to arrange than samurais, one might question the appeal of the unwieldy samurai market, but there are factors that keep an important chunk of yen-denominated bond issues by foreigners at home. Euro-yen bonds are not covered by the Nomura Bond Performance Index (BPI). This puts them out of bounds for most Japanese pension funds, which are among the major investors in samurais, because the funds often have internal controls that require them to hold only BPI-listed bonds.

Conversely, issuers like to sell to Japanese institutions because they are regarded as loyal investors who generally hold bonds to maturity. That is important, says Mr Ishihara, because after the US, Japan is the world's second largest institutional investor market .

Taken together, these factors mean that the samurai market will survive and probably grow modestly, but it is not about to be integrated into the bigger, more diverse world of eurobond issues. "The Eurobond market is an ocean," says an analyst at one of the big four Japanese underwriters. "Samurais are a private pool reserved (with a few exceptions) for Japanese underwriters to swim in."