Investment banks have experienced huge changes since the global financial crisis and are still struggling to adapt their business models. But while the industry might have to make do with much lower returns in future, it is far from being on its knees.

The mid-2000s were glory days for investment banks. Amid high global economic growth, their trading, advisory and underwriting revenues rose year after year. Many of the biggest institutions generated huge profits from their principal investment arms, which operated like private equity firms. Graduates from top universities flocked to Wall Street banks and their European counterparts, lured by salaries dwarfing what those in other industries could hope for.

Editor's choice

Regulation was lax. But that, thought bankers and financial policy-makers, was for the best. The supposedly efficient markets would punish any bank that took too many risks. Moreover, the outlook for the US and other major economies was bright, which could only mean more good times ahead for investment banks.

The storm after the calm

The global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 and subsequent slump in the developed world shattered this cosy situation and changed investment banking for good.

Today, there are fewer firms. Of the five big US broker-dealers, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch either collapsed or were taken over. Only Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley still exist as independent institutions, and even they had to convert into bank holding companies at the height of the turmoil, effectively ending the era of Wall Street’s pure investment banks.

The banks that remain are generally smaller than they once were. Morgan Stanley’s balance sheet peaked at more than $1100bn in 2006, but stood at $832bn at the end of last year, according to The Banker Database. UBS, one of the European banks to suffer the most from the US subprime mortgage meltdown, has seen its assets almost halve to $1100bn since 2007.

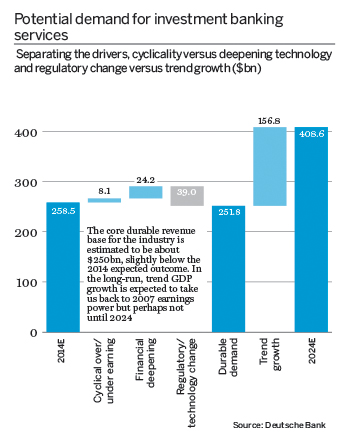

Revenues have fallen across the sector. Global investment banking turnover was a record $409bn in 2007, but will reach just $259bn this year, according to a recent report by Deutsche Bank into the future of investment banks (see chart).

Profits have also taken a hit. Goldman made a return on equity (ROE) of 33% in both 2006 and 2007. Now, it generates an ROE of just over 10%, which barely covers its cost of capital. But it is scarcely alone; few other banks with big investment banking divisions surpass that level by much.

Cyclical or structural

There is debate among investment bankers about whether revenues and earnings are low for cyclical or structural reasons. The optimists believe the industry will regain its swagger once the US and European economies fully recover and quantitative easing ends, which should increase volatility and thus banks’ foreign exchange (FX) and government bond trading margins.

The majority, however, think that structural shifts have rendered a return to the pre-crisis ways of doing business as impossible. Deutsche’s analysts are in the latter camp. They predict that global investment banking revenues will only reach $400bn again in 2024, by which stage they will be 48% below 2007 levels relative to gross domestic product.

One of the main causes of investment banks’ decline is the new regulations they have to abide by. In the past five years they have been forced to raise billions of dollars of capital to meet new standards set by the Basel-based Bank for International Settlements, an organisation for central banks. Fixed-income businesses, which grew rapidly in the 2000s and policy-makers felt were largely to blame for the crisis, have been extensively targeted. “When the outline of Basel III was first published late 2009, nobody quite understood what it meant,” says Christopher Wheeler, a banking analyst at Mediobanca. “By mid-2010 they realised it meant a massive amount of extra capital being required to support certain investment banking activities, especially fixed-income businesses.”

Tougher capital rules have combined with restrictions on the use of leverage, low interest rates and bans on many types of proprietary trading to squeeze fixed-income returns. A few banks, including Deutsche, have responded by bulking up their operations. “In this situation, you need scale,” says Hakan Wohlin, Deutsche’s global head of debt origination.

But such examples are the exception. Most banks have cut their fixed-income arms, as well as their trading of currencies and commodities. “The glory days of the fixed-income trader are over,” says Tim Skeet, a managing director at Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and board member at the International Capital Market Association, an influential trade body. “For about 20 years, the revenues generated by fixed-income trading were the main driver for a lot of investment banks.”

Struggling to adapt

Other businesses affected include principal investing. Analysts cite Goldman as an example of a bank struggling to adapt to the new environment. “Some have suggested Goldman Sachs had almost become a private equity house before the crisis,” says Mr Wheeler. “It had a big trading arm. But it was a making a fortune in principal finance, something it has had to subsequently cut back on. So, it’s been hit on two fronts. Not only does it have to hold much more capital, but some of its most profitable business lines have had to be discontinued.”

Experts say this was precisely the aim of regulators, who sought to make banks safer not just by increasing their capital levels, but also by coercing them away from businesses deemed risky and volatile. “It’s not simply about holding more capital and being less leveraged,” says Jan Pieter Krahnen, professor of finance at Frankfurt’s Goethe University. “It goes deeper. The intention is not just to tighten the screws, but to redefine banks’ business models.”

While bankers generally agree with the bulk of regulatory reforms, they warn that some have the potential to destabilise financial markets. Many lament that secondary liquidity in the fixed-income market has declined in the past few years, a consequence, they say, of banks being penalised for having large inventories of bonds. “Because of the new capital and liquidity costs, traders can’t take the cash or derivative positions they did before,” says Mr Skeet. “It means that right across the industry, secondary trading has fallen off a cliff. Arguably, it’s gone way too far. It’s very worrying.”

Markets have so far coped, but only because central banks have flooded them with liquidity through quantitative easing, which has driven yields to all-time lows. Bankers are concerned the situation will change once interest rates in the rich world rise. While the eurozone is still far from that point – its central bank has just cut rates and announced a new bond-buying scheme – the US, whose monetary authorities are expected to make the last of their bond purchases this month, could start to hike next year.

Unchartered territory

If investors try to sell their bond holdings en masse as rates climb, the absence of banks acting as dealers could exacerbate the fall in prices. “Through regulation and other pressures on banks, [the regulators] have undermined the foundations of liquidity support in the secondary markets,” says Bill Winters, chief executive of Renshaw Bay, a London-based asset manager, and former co-head of JPMorgan’s investment bank. “Because of the lessened role of banks, there will be inadequate buffers for the transition that will eventually come after quantitative easing ends.

“We’re in uncharted territory in terms of how the market is going to respond. It hasn’t been tested yet.”

How markets react to rising interest rates will be crucial for banks. The pick-up in volatility will widen FX and government bond trading spreads.

Yet fixed-income businesses overall could be negatively affected, especially if primary issuance markets, which have been so buoyant in the past three years with borrowers across the credit spectrum taking advantage of ultra-low yields, slow down.

Most bankers say that while they are optimistic central banks can ensure rates rise smoothly, which will lessen the extent of outflows from bond markets, the situation will be particularly bad if they climb rapidly. “Rising interest rates could have profound implications for fixed-income markets, including reduced corporate issuance, declining secondary market prices and increased volatility,” says David Solomon, co-head of investment banking at Goldman.

Litigation is another factor hindering investment banks. In the past few years US and European watchdogs have been ever more assertive, with the size and frequency of their fines rising dramatically. Deutsche’s report estimates that conduct risk costs for Bank of America, Citi, Goldman, JPMorgan and Morgan Stanley between 2009 and the second quarter of 2014 – most of them relating to the sale of mortgage-backed securities before the crisis and market transgressions – totalled $75bn. The figure for European banks with big investment banking arms (excluding Deutsche itself), which were hit for similar reasons as well as for breaching US anti-money laundering rules, was $48bn.

More fines coming

More fines are expected once global investigations into the alleged manipulation of FX markets and high-frequency trading are finished.

Deutsche believes that European investment banks face a further $41bn of conduct risk charges, for which they have set aside reserves of about $20bn, leaving them with a net exposure of $21bn.

Bilal Hafeez, a strategist at Deutsche and one of the report’s authors, says that in the long run the scale of fines is likely to drop, partly because of measures banks have taken to bolster their compliance departments. “We assume that most of the litigation costs have already been paid or reserved for,” he says. “And because banks have tightened their controls and hired many compliance officers, their problems regarding conduct should be reduced in future.”

Predicting future legal costs is, however, notoriously difficult. Many European investment banks trade well below their book values, which probably reflects equity investors’ fears about litigation. Neil Woodford, a prominent UK fund manager, recently sold all his shares in HSBC because he thought ongoing investigations into interbank and FX rates could lead to more penalties for the bank.

“The problem for banks is that there’s complete and utter uncertainty about litigation,” says Mediobanca’s Mr Wheeler. “It comes out of the blue. Who knows what could come next? To me, it feels like a 10-year cycle that began in 2010. There’s a long way to go before we can say it’s done.”

Banks have mostly been able to absorb the fines so far without greatly damaging their capital ratios. But that could change should litigation costs keep rising. “When you look at the eye-watering level of some of these fines, they clearly deplete capital bases,” says RBS’s Mr Skeet. “If they get any worse, they have the potential to undermine a bank’s viability.”

Two more potential threats with which investment banks will have to deal are technological advances and the growth of shadow banks.

New technology has disrupted banks’ operations in the past. The advent of electronic FX trading in the early 2000s led to higher volumes, but this was not enough to offset spreads shrinking by 85%, according to Deutsche.

Electronic trading is likely to become more common in the fixed-income market. Deutsche thinks this could hit banks’ revenues to the tune of $39bn the next decade. That would, however, amount to a lesser shock than what FX experienced, mainly because the fixed-income market contains a far greater variety of products, issuers, tenors and structures. “Lots of fixed-income products might be difficult to trade electronically,” says Mr Hafeez. “For products to be traded electronically, they need to form deep and liquid markets and their contracts need to be standardised.”

Shadow banks lurk

Shadow banks – a broad term encompassing non-bank financial institutions such as asset managers, private equity houses and hedge funds – have become more prominent since the crisis. They tend to be lightly regulated relative to banks and have less stringent capital and leverage requirements.

Several bankers believe that shadow banks are a threat to their businesses, not least in areas that banks, thanks to new regulations, can no longer dominate as they did before 2008.

Perhaps reflecting this, Anshu Jain, Deutsche’s co-chief executive, said in September that shadow banks must face stricter regulations. “One principle is crucial: ‘equal treatment for equal risk types’,” he said.

Among the major trends that could boost banks is financial deepening in emerging markets, most of which have small capital markets for the size of their economies. Investment bankers hope that China will continue to liberalise its financial sector in the next 10 years, which would inevitably cause its bond, equity and mergers and acquisitions markets to grow.

Others believe that the shrinking of bank balance sheets will result in the expansion of Europe’s corporate bond market, which would give investment banks a new revenue source. European capital markets have plenty of room to grow, given that they only provide about 25% to 30% of the credit used by companies on the continent (in the US, the figure is about 70%).

Moreover, bankers have long argued that Europe needs to follow the US in financing more assets through securitisation markets rather than banks. “If bank balance sheets are going to shrink, then the European securitisation market has to take off,” says Gaël de Boissard, co-head of investment banking at Credit Suisse. “There are a whole load of assets that could logically and safely be financed through securitisation, as they are in the US. European banks cannot continue keeping these assets on their balance sheets.”

For this to happen, officials will have to encourage institutional investors such as pension funds and insurers, which, unlike banks, have long-term liabilities, to play a great role in the securitisation market. “These types of investors are the only ones that have the liabilities that enable them to acquire long-term assets without increasing their liquidity risk,” says Antonio Cacorino, managing principal of StormHarbour, an independent investment bank.

Since the crisis investment banks have struggled to adopt business models as lucrative as those they had before 2008. This problem is unlikely to abate any time soon, especially since banks still do not know what the final make-up of the new regulatory regime will be. The ongoing debate about leverage ratios is a case in point. What was meant to be a simple measure of a bank’s strength has become fiendishly complex, with national regulators differing over the correct ratio and what types of capital will count towards it. “Thanks to new regulations, trying to work out how to run and fund an investment bank has become very complicated,” says Mr Wheeler.

Wither global universal banking?

One result is that global universal banking seems to be on the wane. Amid deleveraging and higher capital requirements, banks that used to have grand ambitions for their investment banks, such as RBS and Barclays, have since retreated to their regional markets or cut businesses to focus only on the ones they have traditionally excelled in. Those that still want to operate globally and universally, such as JPMorgan and Deutsche, are few and far between, with bankers questioning whether institutions actually increase their risks, rather than hedge them, when they expand into more regions and businesses.

“Global universal banking needs to prove its validity,” says Marco Mazzucchelli, former deputy head of RBS’s investment bank and now at Julius Baer, the Swiss private bank. “Of all the business models, it seems to be struggling the most.”

What is clear is that investment banks will have to be far more sophisticated in the future with their allocation of capital. Before, they tended not to look at the capital and liquidity costs of businesses in isolation, instead subsidising those that were less efficient with the profits of those that generated surplus capital. This had the effect of artificially boosting the profitability of some divisions. “Anecdotal evidence suggests that universal investment banks treated all business segments alike in their internal cost of funding models,” says Goethe University’s Mr Krahnen. “This led to a misallocation of capital. It is a mistake that can have huge repercussions.”

Even the banks that manage to create efficient business models cannot hope to be as lucrative as they were in pre-crisis years. “The only way you can achieve a 20%-plus ROE is if you do it with much less capital,” says Mr Winters of Renshaw Bay. “Independent investment banks without the need for capital might get there. But in the capital-intensive parts of the industry, I don’t think those returns are possible.”

But the prognosis is far from being altogether bleak, say bankers. They insist that as well as being better at calculating risks and allocating capital, the industry has used the crisis to improve its governance, become more transparent and reform its pay structures so that bankers take the long-term consequences of their decisions into account.

Moreover, some say the resilience shown by investment banks over the past five years in the face of such pressures proves that they will always be needed to intermediate between those wanting capital and those that can provide it. “The death sentence given to investment banking was a little premature,” says Mr Mazzucchelli.