A wave of regulations to force creditors to share the pain when 'too big to fail' banks run into trouble will panic investors, say the bankers. But some investors argue the proposals need to go even further.

Who would be a SIFI these days? When Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008 and bank funding and capital markets froze up, every bank wanted to be a 'systemically important financial institution' - too big and too interconnected to fail, and therefore worthy of government support. Now SIFIs are officially classified as a public menace, and their managers are wading waist-deep through a sea of new regulations designed to avoid tax-payers ever having to bail them out again.

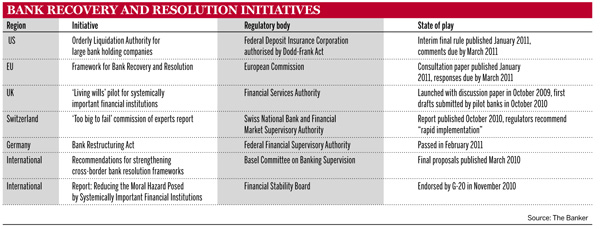

Less than a month after markets had begun to digest the latest draft of the Basel III capital regulation proposals published in December 2010, the European Commission produced a consultation paper on a possible EU framework for bank recovery and resolution. It runs to more than 100 pages, covering six different chapters and three annexes. Struggling to swim through the rising tide of paperwork, it seems as if markets focused on one particular sub-section: the concept of bailing-in senior unsecured debt to recapitalise a troubled large bank.

This idea should not really come as a surprise. The German Bundestag was already discussing its new Bank Restructuring Act, ultimately passed in February 2011, that would give the local financial regulator BaFin a broad range of powers to impose haircuts on senior creditors in a bank resolution scenario. Alistair Asher, global head of the financial institutions group (FIG) at law firm Allen & Overy, says the UK Banking Act already incorporates wide powers on bank resolution. And he points out that these can be augmented by parliament in a single sitting - as they were to facilitate the emergency nationalisation of Northern Rock in February 2008.

There is also growing regulatory enthusiasm, especially in Switzerland, for contingent convertible bonds (CoCos), that convert into equity if the Tier 1 capital adequacy ratio falls too far. But this is still a very new and niche product, and one in which conversion to equity is a known and clearly defined possibility from the start. For the already large universe of senior unsecured creditors, by contrast, the rules of the game now seem likely to change significantly.

All change

“I can imagine people will look at the [senior unsecured] instrument and say the possible consequences of this are worse than what I used to buy, therefore I must get paid more. Spreads for the asset side have to go up, and the end-consumer will bear the brunt of that,” says Prasad Gollakota, head of European capital solutions at UBS.

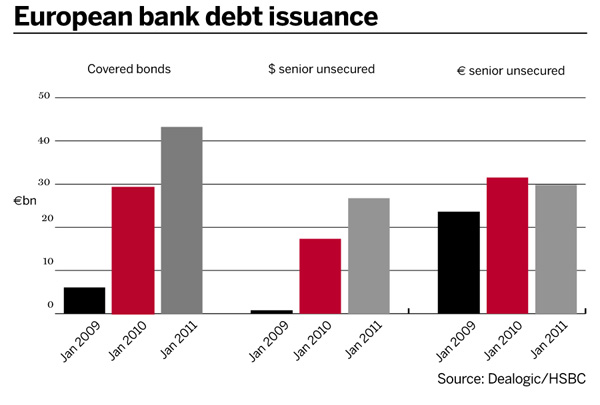

Syndicate managers for FIG debt capital markets (DCM) say this response is already visible. A heavy burst of senior unsecured issuance in European markets in the first two weeks of January tapered off quickly after the EU consultation paper.

“The noise surrounding bail-ins resulted in a slowing of the senior new issue market in Europe as investors became cautious on what they were prepared to invest in. We saw new issue premia increase and less of a bid for duration of five years or longer, although several national champion banks have printed longer-dated trades more recently,” says Hugo Moore, head of European frequent borrowers at HSBC in London.

Investors say yes

Arguably, a bail-in of senior unsecured debt for banks is no different from the insolvency risks faced by investors in the bonds of any other type of corporate. Paul Sharma, head of prudential regulation at the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA), says the real innovation lay in far-reaching government responses to the 2008 financial crisis.

“The insolvency regime is inherently a bail-in regime - once capital is exhausted, senior creditors get a haircut. But that did not happen during the financial crisis because government interventions came in before that, in part because if you put a bank into insolvency, other consequences follow: loss of confidence in banks generally, and lack of supply of credit to the economy. So you can view bail-in as an attempt to achieve a conventional insolvency without the adverse systemic consequences,” says Mr Sharma.

But wearing his other hat - as head of prudential regulation for insurers - Mr Sharma says he recognises that what works well for bank regulators does not necessarily look so good for key institutional investors. “I would not say they could not hold any bail-inable bank debt, but I would not want to see a predominance of it in the portfolio of an annuity writer,” he says.

Fund managers report that institutional investors have already scaled back their allocations to senior unsecured bank debt, sometimes to zero. But in practice, major institutional investors actually appear to welcome the proposals.

In the first instance, they should remove the ambiguity of implicit government support - which only became explicit with the issue of government-guaranteed bank bonds in late 2008. Ratings agency Moody’s warned in February 2011 that they were examining whether to revise their ratings on senior unsecured bank debt, because bail-in proposals could lead to “exceptional cases where senior creditors are also at risk”, not just subordinated creditors.

“Whether bank debt paper is 'fairly' priced is difficult to say. However, what we consider a healthy development is that bank debt, as with any other financial market security, is not being perceived as risk-free,” says Guido Fuerer, head of the chief investment office at Swiss Re, which has almost $100bn in fixed-income securities in its portfolio.

Fuller thinking

Institutional investors are also thinking in a comprehensive way about their entire portfolios. In particular, sovereign debt is an even bigger asset class than bank debt, and a crucial one for insurance and pension funds.

Tamara Burnell is head of financial and sovereign research for the UK-based M&G Investments, which manages about £110bn ($178bn) in fixed-income assets for institutional investors, including about £60bn for its parent company, the insurer Prudential. She argues that the EU proposals should be implemented quickly to stave off any fresh fears about sovereign creditworthiness, and even suggests that they do not go far enough, because they include the possibility of grandfathering existing senior unsecured debt.

“We would have a bigger sovereign debt crisis to deal with if people wake up to the idea that any senior debt that cannot be bailed in is effectively government guaranteed. The Ireland situation has shown that it is wrong to say that banks will only have to issue some bail-inable debt sometime in the future,” says Ms Burnell.

She also casts doubt on the idea of a targeted approach mooted in the consultation paper, where only a certain pre-specified layer of senior unsecured issues would be subject to bail-in. She says this would still leave a large implicit sovereign liability, and might continue to encourage unsustainable risk-taking by banks based on that moral hazard.

The thought of retroactive bail-ins may be less alarming than it sounds. When Investec Bank tapped its regular Euro Medium-Term Note programme in January 2011, it issued a simple supplement to the existing prospectus warning that any UK legislation to implement the EU’s proposals “may have an adverse effect on the position of noteholders”. The bail-in genie is already out of the bottle, even for existing bond issues.

At Pimco, the giant fixed-income fund manager with $1200bn under management that is owned by Allianz insurance group, head of global bank credit Philippe Bodereau says the proposals should bring discipline to debt investors as well as to the banks themselves.

“Analysis of banks will need to become a lot more sophisticated; smaller pension funds sometimes used to buy senior debt themselves without analysing the whole capital structure, but they cannot do that anymore,” he says.

Too many layers

Mr Bodereau notes that it is more difficult to analyse potential haircuts on bank debt than on corporate debt, for two reasons. First, as Lehman demonstrated, a bank can fail in the space of a weekend, whereas a corporate entering Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings would typically have at least a month to negotiate an orderly exit from bankruptcy with shareholders and creditors. And secondly, banks are regulated entities, especially at the point of failure.

“The regulator is going to have much more freedom to impose the haircut on creditors, because the period of time for a bank to achieve recovery is much shorter [than for a corporate]. If you are a regulator, you have many incentives to be conservative, to force the bank to carry out a tough stress test and recognise large losses – having reached the point of intervention, you are going to want to leave the bank overcapitalised afterwards,” says Mr Bodereau.

It is this uncertainty about how regulators will handle bail-ins in practice, rather than the principle itself, that most unsettles the market. Gerald Podobnik, co-head of European capital solutions for Deutsche Bank, says regulators may be coy about answering too many questions entirely unambiguously. While markets prefer clarity, supervisors want flexibility to respond based on the specific circumstances of the crisis that they face.

But he is concerned that a side-effect of the the new regulations is to move away from one approach advocated during the financial crisis – to simplify bank capital structures. If the targeted bail-in approach is used, for example, banks could end up with a mix of senior debt that could be bailed in, some that could not be bailed in, and potentially also CoCos, plus the new, Basel III-compliant Tier 1 and Tier 2 hybrid bonds that are deemed genuinely loss-absorbing, all with varying triggers for write-down or conversion to equity. And the EU proposals might create yet another layer after a bail-in has actually occurred.

“To motivate investors to provide funding to any institution that is newly restored, those who invest immediately after a bail-in would potentially receive super-senior status, to get a bank back to the funding market after a bail in. But that could create operational difficulties and make the hierarchy of instruments more complex,” says Mr Podobnik.

And the thorny question of what not to bail in is also causing some of the most intense debates on the Basel Committee and the Financial Stability Board. While everyone agrees retail depositors should be protected, wholesale deposits are sometimes little more than a proxy for capital markets funding.

Meanwhile, given the systemic crisis caused by a freeze-up of short-term interbank funding markets in 2007 and 2008, regulators are keen to exempt short-term debt from bail-in, but are apparently not even close to reaching a consensus on how to define it. If it is defined too rigidly, SIFIs might be tempted to shorten their funding duration to benefit from the exemption. Yet it was precisely the overdependence on short-term commercial paper markets that exacerbated the liquidity squeeze in 2007-08.

Covered bond alternative

One exemption that seems to have prompted consensus is for covered bonds. These have recourse to the issuing bank and are also secured against ring-fenced pools of balance sheet assets. They should therefore have the legal framework to resolve themselves without regulatory intervention. That certainly seems to be the market view, as European bank covered bond issuance exceeded senior unsecured in January 2011 (see chart).

Most major banking markets now have explicit covered bond legislation, including the UK since 2008. A US covered bond law narrowly failed to win enough votes to be passed with the Dodd-Frank Act, but Mr Fuerer believes the structure could still become important there.

“In our view, the covered bond market specifics with the German-style double risk retention characteristics are appealing not just for Swiss Re, but for investors more generally. The crucial question is how the US housing market will be financed in the era after Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s temporary conservatorship. It could well be that the German-style covered bond market specifics will become more important in financing the US housing market,” he says.

Christoph Hittmair, head of European FIG DCM at HSBC, says banks that had previously not optimised their cover pools, or are headquartered in jurisdictions where cover bond legislation is relatively new, are now focusing on structuring assets appropriately to establish a dedicated covered bond issuance programme. Domestic UK investors have quickly developed an appetite for sterling-denominated covered bonds.

This enthusiasm raises a question about how much of a bank’s funding base should be secured credit, without jeopardising the amount of good assets available to repay depositors in the event of a bank failure. Canada has already looked at limiting the proportion of funding that can be issued in covered bond format, and Italy restricts covered bond issuance to a set proportion of Tier 1 capital. Ralf Grossmann, head of covered bond origination at Société Générale, says banks would prefer case-by-case discussions on maximum covered bond issuance as part of the overall supervisory process, rather than fixed blanket restrictions.

“Business models vary, and it is possible to envisage a situation where, for example, a bank might need to increase wholesale funding because its retail depositors were moving away to investment products outside the bank instead. In that case, the bank could increase the size of its cover pool while still providing enough good quality assets to cover depositors, because the size of deposits is falling,” he says.

At the UK FSA, Mr Sharma says the thinking at the moment is that setting minimum amounts of funding that can be bailed in would be preferable to placing maximum limits on covered bond issuance.

US market precedents

In any case, covered bonds rely on a suitable pool of assets, usually mortgages. They cannot cover all the funding needs of every bank, especially those that do not have a mortgage-driven business model. This means European issuers still need to find investors who are comfortable with the concept of haircuts for senior debt. One such investor base already exists. They are called Americans.

While euro-denominated bank senior unsecured debt issuance by European banks fell year on year in January 2011, the issuance of dollar-denominated Yankee bonds jumped more than 50% (see chart). Mr Hittmair says that, as fears over eurozone sovereign debt have abated somewhat, US investors can get comfortable with good quality European names, and have been confronted with the debate around bail-ins for longer than European investors.

That familiarity is easily explained. Although several US SIFIs, most notably Citi and Bank of America, received government bail-outs in 2008 that avoided any senior debt haircut, there were also 398 banks under Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) supervision as at the third quarter of 2010, many of which are going through conventional insolvency processes. By far the largest bankruptcy to date is that of Washington Mutual (WaMu), which failed in late 2008 with assets estimated at $327bn and was ultimately bought by JPMorgan for less than $2bn.

Several different classes of creditors split between WaMu bank and its holding company WaMu Incorporated managed to reach a possible deal after 18 months of negotiations, which could see senior creditors in WaMu Inc receive much of the face value of their bonds. But the deal could still be scuppered, after a judge granted permission for further hearings on objections filed by shareholders in the holding company, even though their economic interest appears to have been more than wiped out.

“Recoveries in this creditor deal were premised on timing issues and subtle aspects of the deal. So the court has removed one key structural pin, and the deal is starting to wobble. This could still turn into a liquidation rather than a Chapter 11 reorganisation,” says Thomas Lauria, a partner at White & Case, who is representing the senior creditors.

This is not the first time a US bank has met a litigious end, but lawyers working with another bank holding company, AmericanWest Bancorporation (AmWest), may have found a solution within existing law. Kenneth Kohler and his team at Morrison & Foerster managed to win bankruptcy court backing for a scheme to sell AmWest’s distressed bank subsidiary (the holding company’s only asset) to private equity fund SKBHC under Section 363 of Chapter 11, without the need for FDIC intervention. Section 363 allows for a bank holding company in Chapter 11 to auction one of its assets to aid recoveries, without investor consent - the legal assumption is that a fair auction process will achieve maximum recovery for investors in any case.

The legislation may not originally have envisaged selling an entire bank as one asset, but the court approval has now set a precedent. So too has the careful crisis management campaign that allowed AmWest holding company to enter bankruptcy without triggering a run on the bank’s deposits, by explaining in the local media that the bank was being saved. It is estimated that keeping AmWest’s bank alive and selling it saved the FDIC about $300m in liquidation costs.

“Under a 363 procedure, the bankruptcy court will listen to arguments from all participants on what the fair price of the sale should be, but no one has statutory rights to stop the sale regardless of where they are in the capital structure. So in a bigger, more complex bank there would clearly be more participants at the hearing, but there is no reason why the procedure should not work. Albeit accidentally, by taking away the need for creditor consent we have effectively created a requirement for creditors to bail in,” says Mr Kohler.

Part of the package

But AmWest is specific to US law, and more importantly, it is not by any measure a SIFI. The vital difference with a much larger organisation is whether a bail-in would be enough to prevent the risk of a wider loss of confidence that provoked governments to indulge in such large bail-outs in late 2008.

Bail-ins will need to fit together with the initiative for banks to draft 'living wills', contingency plans for recovery and resolution scenarios, which The Banker will be considering in its April 2011 edition. And Mr Sharma at the FSA says the fight against systemic risk and contagion goes far beyond forcing creditors to help recapitalise stricken banks.

“There are many other elements including higher and better capital and liquidity, new attitudes toward risk among management, more intrusive and intensive supervision, reform of accounting and accounting standards. One should be cautious about thinking that any one technical solution such as bail-in solves the problem, rather than just contributing to solve the problem,” says Mr Sharma.

In fact, Mr Gollakota at UBS wonders if the reaction to bail-in might not be overdone. A UBS assessment of some of the large European banking groups that received government support during the financial crisis suggests that, if they had been fully Basel III-compliant before the crisis, it is likely they would have withstood the losses suffered without needing recapitalisation from government, or even from senior unsecured creditors.

“The regulators are imposing buffers on top of buffers, therefore the overall risk for any bank that senior debt will really ever get affected, still less get written off entirely, is much lower than it was before. The scenario has to be even worse than what many banks went through in 2008-09. So from an economic perspective, it is questionable whether senior unsecured would become any riskier going forward than it was pre-crisis,” says Mr Gollakota.