The Banker/Innovest Top ESG Global Banks listing identifies the institutions that are at the forefront of the trend for environmental, social and strategic governance to inform business strategy, providing a benchmark for the ESG effect. In our launch of the ranking, we find those that take ESG seriously have a better stock market performance.

Many global banks insist that issues such as environmental, social and strategic governance (ESG) – variously called corporate social responsibility (CSR) or sustainable finance – are high on their list of priorities. But the profits and reputation of many of them collapsed in the recent and ongoing subprime debacle, which is evidence that a focus on these factors is not embedded in their investment choices.

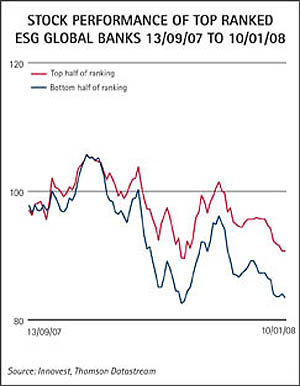

The Banker partnered with Innovest Strategic Value Advisors, which is ranked number one by Thomson Extel for the provision of extra-financial research to the investment community, to rank global banks in terms of ESG. Our definition of ESG involves more than just the avoidance of lending to a mining company involved in a project that is boycotted by the World Bank, or the reduction of carbon emissions, important as these factors are. It also involves focusing on risk-adjusted profits, a strategy that we believe will become ever more crucial to a bank’s performance. It is about marrying the heart and the head. Already, share prices of the global banks that have taken on board this forward-thinking attitude have outperformed those that have not yet fully incorporated ESG (see graph below).

The Banker/Innovest Top ESG Global Banks listing uniquely focuses on global banks, thus avoiding the tendency in rival lists for smaller microcredit or co-operative institutions to win prizes when their effect on the world is minor. The global banks are heavyweight institutions that shape the world in which we live.

Opportunities to grasp

The banks that have come out top of the list are ones that appear intent on grasping the opportunities in ESG, not just avoiding the pitfalls. The UK’s Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) is a case in point. It has strong credentials in financing the renewable energy sector. Without much fanfare, it focused on thoroughly incorporating environmental and social due diligence into its normal lending and investment process, notes Innovest.

It is no coincidence that RBS was named Global Bank of the Year in The Banker Awards 2007 (see The Banker, December 2007). Focusing on profits and takeovers – the UK bank is busy incorporating parts of ABN AMRO’s businesses – does not preclude fully incorporating ESG, a point that needs to be taken on board by the more radical non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

There are, however, two caveats to The Banker/Innovest list. One is that we are at the beginning of a trend – albeit one signalled by The Banker in its April 2002 cover story (The importance of being good – why unethical banks will not survive). An AAA rating does not imply flawless implementation and execution of an ESG policy. For example, in its 2006 sustainability report, RBS did not mention concerns raised by its involvement in two controversial energy projects – a gas project in the Niger Delta and an oil project in Alberta, Canada – according to BankTrack, a network of NGOs that tracks the operations of the private financial sector. (In the interests of transparency and maintaining a dialogue with responsible organisations in the non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector, see the box on page 30 where BankTrack has set out its rather more negative view of the positioning of the global banks.)

A second caveat to The Banker/Innovest list is the fact that there are limits to the research. For instance, Standard Chartered, a bank that has been at the forefront of the industry in emphasising ESG since chairman Mervyn Davies was named CEO in 2001, only manages an AA rating. The bank, headquartered in the UK but with most of its operations in emerging markets, lends to many companies that do not have an ESG rating because they are smaller and in emerging markets, notes Innovest. But that gap will narrow as more emerging market companies are incorporated into ESG ratings.

Allied to this, banks do not disclose data on their bilateral loans, private placements or short/hedge positions in asset management, nor data on their trading performance. So the judgements taken are on a cross-section of their financing activities. However, we expect the level of disclosure to increase in the coming years due to regulatory, shareholder and other pressures.

Points of interest

The ESG listing raises some particular points of interest:

- Banks that create the most publicity about their ESG policies are not necessarily top of the list. Bank of America pledged to invest $20bn in environmental markets yet it did not rank in a single renewable energy or clean tech league table. It was also one of the worst performers in its allocation of capital to outstanding ESG companies.

- The top ranked global banks in the list manage ESG risk as an earnings liability rather than a brand liability. ESG due diligence is managed in the risk division, as opposed to the marketing or public affairs division, and is enforced by the credit risk committee and/or the chief risk officer.

- Interesting results include French banks Société Générale and Crédit Agricole and Spanish banks Grupo Santander and BBVA, along with the UK’s RBS, being the ones with an AA or AAA rating in ESG, along with Standard Chartered.

- Dutch bank ABN AMRO is not a surprising choice with its AAA rating but the folding of parts of the Dutch bank into RBS does not automatically mean that in the February 2009 listing RBS will be given an AAA rating. The UK bank’s top rating is a result of its operating mainly in developed country markets where it has the knowledge to make profits without incurring excess ESG risk. The Dutch bank’s rating is based in part on the ability of its outstanding, experienced ESG team in evaluating the environmental, social and political risks in emerging markets, as well as developed markets. The merged rating will depend on how well the ABN AMRO advantage is integrated into RBS as the UK bank enters a host of new markets in places as diverse as Pakistan and the Philippines.

ANALYSIS OF THE BANKER/INNOVEST TOP ESG GLOBAL BANKS LISTING

Key ESG mega-trends, such as climate change, energy security, the increasing cost competitiveness of renewable energy and the emergence of poor people as a bankable retail demographic, are reconfiguring the global economy. In Innovest’s view, the long-term competitiveness of a bank increasingly depends on its ability to navigate this new risk landscape.

In the following paragraphs there is a breakdown of how our model evaluates banks’ ESG performance. We look at about 50 metrics, so the percentages next to each category are approximations of how heavily each factor is weighted in the model.

ESG risk exposure (30%)

Innovest has developed a Capital Allocation Benchmarking Analysis (CABA) model, which examines the ESG performance of the companies, sectors and countries that banks have financed. To do this it looked at all the syndicated loans in which each bank has participated, all non-broker dealer equity investments and all of the debt and equity that a bank has underwritten. Then the Innovest scores of all the companies that a bank has financed were compiled, with more weight given to environmental high-intensity sectors such as energy, industrials and materials.

Similarly, the ESG performance of all of the countries and sectors that a bank has financed was analysed.

In the global banking sector, the average amount of deals analysed per bank was $454bn. The sample size analysed through CABA inevitably varies depending on the amount of publicly filed deals and investments in which a bank has participated. CABA does not look at bilateral loans (which are not publicly filed) and cannot differentiate between asset management positions that use the bank’s own capital and those that use clients’ capital. CABA provides a glimpse into the ESG impact of a bank’s loans, investments and capital markets activities, but should not be viewed as a complete picture of a bank’s capital allocation.

ESG due diligence (30%)

In the global banking sector, all companies have some strategy for managing ESG risk, but it rarely translates into tangible change on the ground where bankers are closing deals and making investments. The question is no longer whether a bank is managing environmental and social risk, but how; and, more importantly, whether they are doing it in a way that delivers superior long-term returns to investors.

We look for three traits in the banks. First, does the group risk function ‘own’ ESG due diligence rather than the public affairs or communications functions? Because being ‘green’ is so popular, when group risk is not in charge banks tend to prioritise ESG risks based on their broadcastability rather than their financial relevance.

Second, do front-line bankers and asset management teams incorporate ESG due diligence into the capital commitment process? This is the biggest challenge for any bank. A banker’s first priority is hitting quarterly and annual targets. Any additional layer of due diligence is often unwelcome. We examine whether a bank has struck the right combination of top-down enforcement and bottom-up consensus building to integrate ESG due diligence fully into the capital commitment process.

Third, does senior management understand why ESG risk is significant and are they realistic about what it takes to manage it effectively? Managing ESG risk often entails foregoing short-term profits in the name of prudent long-term risk management. Any bank that avoids coal because of its long-term environmental and regulatory risk will similarly have some explaining to do. It is essential that senior management communicate with shareholders and division directors about the short-term sacrifices that ESG risk management entails and how it will add superior value over the long term.

Strategic profit opportunities (15%)

In this category, we look for banks that are investing more, and with better returns, in new sustainability markets such as clean tech, renewable energy and microfinance. However, these markets are too small to have any real impact on profit or revenue in the banking sector and are therefore not heavily weighted in the analysis. In sum, a bank’s strategic profit opportunities say more about strategy than actual performance.

Stakeholder capital (15%)

All banks have joined stakeholder groups that address ESG risk but these memberships rarely have any impact on a bank’s ESG performance on the ground. We look for banks that build partnerships that enhance their ability to forecast and price new generation ESG risks.

Standard Chartered is one of the few banks that effectively leverages its stakeholder partnerships to achieve this result.

Human capital (10%)

Human capital is a critical driver of ESG performance but is almost impossible to measure. There are good metrics such as HR consultancy Hewitt’s survey, which measures staff engagements, but this score is not available for all banks. We took into account staff satisfaction surveys, inflows/outflows of executive traffic, and staff turnover. This data is not universally available, however, so we do not heavily weight human capital.

ACTION VERSUS LIP SERVICE

Many of the global banks that are adopting stringent policies that deal with the social, environmental and human rights aspects of their operations are failing to implement them in day-to-day investment decisions, according to BankTrack, an international NGO network that monitors the financial sector, in its Mind the Gap report published in December (www.banktrack.org). The progress so far in developing credit policies with an ESG component is slow and unequal, with some banks leading the way and many lagging far behind.

In the report, BankTrack evaluates the credit policies of 45 major international banks on three levels: the content of sector and issue policies, the level of transparency and accountability, and the implementation of policies. Policies on everything from agriculture to the arms trade, labour rights and climate change are analysed.

Among other findings, the report – an annual scorecard on the performance of the banks – said:

- The human rights commitments of Rabobank stand in clear contrast to the often vague and aspirational policies of all the other banks.

- Only four out of 45 banks have developed policies for the mining and oil and gas sectors, despite the effect these industries have on global sustainability. The four banks are HSBC, ING, ABN AMRO and Barclays.

- The three Chinese banks surveyed, ICBC, Bank of China and China Construction Bank, all had no publicly available standards on environmental or social financing.