Securitisation seeks redemption in Europe

A few short years ago, securitisation was blamed for triggering the financial crisis and was seen as the root of all evil. However, there are now signs of change, with issuers slowly beginning to reconsider the market as investor appetite returns.

Though the recovery of the US securitisation market is proving far more pronounced than that in Europe, even in the continent where the tool is still suffering from the mauling its reputation received in the post-crisis years, sentiment is improving. At the root of this is a recognition that securitisation can be a valuable capital markets tool, provided transactions are sensibly structured.

Editor's choice

“When securitisation started 25 or 30 years ago, it was to solve a crisis," says Fabrice Susini, head of securitisation at BNP Paribas. "Then, in 2008, it became the scapegoat for a crisis. The problem was not the tool but how it was used in some cases. Securitisation was initially about channelling capital market funding to lending, not about complex arbitrage products and collateralised debt obligations [CDO] squared. That principle remains and is being recognised now.”

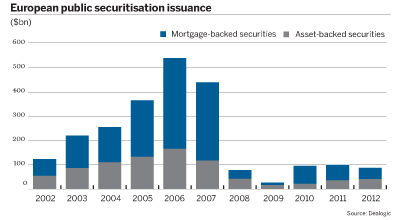

Early 2012 saw a spike of new issuance, fuelling guarded optimism about a recovery in securitisation. In the second half of the year, however, primary issuance fell away as banks used other sources of funding, including the Bank of England’s Funding for Lending Scheme, which allows UK banks to access central bank funds to fuel lending.

“The smooth transmission of credit to the real economy through the banking system is dependent upon, among other factors, a functioning securitisation market, which itself is dependent upon active bank participation as investors in the product," says Allen Appen, head of European financing solutions at Barclays Capital. "So the ability of banks to again invest liquidity in asset-backed securities [ABS] may precipitate further recovery in the European market, but it is ironic that this is happening at a time when banks have a relatively modest need to issue, reflecting an abundance of inexpensive official liquidity and ongoing capital constraints driving deleveraging.”

Deals return

The experience of early 2012 nevertheless has boosted confidence in European securitisation. Demand among investors for deals reaching the market is strong and the secondary market remains active.

"Investor confidence is starting to return. Provided stable conditions continue, [there is] likely to be a greater issuance of commercial mortgage-backed securities [CMBS] this year," says Gareck Wilson, a director at real estate advisory firm Brookland Partners.

Deutsche Annington’s €4.3bn refinancing of its Grand securitisation – the largest real estate refinancing of 2012 – underlined the nascent recovery in Europe’s CMBS market. Although a refinancing rather than a new issue, the deal signalled that issuers and investors are willing to participate in the restructuring of transactions issued at the height of the market.

Deutsche Annington’s Grand transaction was initially issued in 2006 when securitisation structures were at their most aggressive. The financial crisis took its toll on underlying property values and Annington’s ability to repay its debts on time. Negotiations with investors started in 2011, and took more than a year to hammer out but, ultimately, maturities were extended and the transaction was boosted by a €504m equity kicker from private equity firm Terra Firma, which owns the Annington properties. The deal has been watched closely, not least because so many transactions undertaken before the financial crisis need to be refinanced this year.

"There is a wall of CMBS loans maturing in 2013 so the need for refinancing is greater than it has been in previous years," says Mr Wilson.

Mixed signals

Securitisation covers a gamut of different types of deal, some of which have been relatively stable. European whole business securitisations (WBS), for example, have been unaffected by the negative headlines about securitisation, particularly in the infrastructure space. Highlights include a £740m ($1.15bn) securitisation from leisure operator CenterParcs and a £480m WBS from UK water supplier Affinity Water, both of which were well received by investors.

“In the corporate space, secured debt structures have never gone away, especially when you look at whole business deals in the UK," says Andrew Blincoe, head of secured debt markets at RBS. "The Affinity Water deal, for instance, achieved fantastic pricing with very strong investor demand. Similarly, the Center Parcs WBS that RBS led in 2012 saw more than £1bn of issuance and was outside the core infrastructure space. The key to these deals is that there is always a living, breathing business at the heart of the financing and these funding structures have a very strong track record.”

In the broader securitisation market, growth is far slower. In 2006, for example, CMBS deals amounted to more than €60bn. Last year, that figure had slumped to about €1.4bn, according to Brookland Partners. Fitch Ratings predicts public and retained issuance of European structured finance will remain unchanged in 2013 at about €200bn – compared to €310bn in 2011 and more than €600bn in the years before the financial crisis. More positively, however, a higher proportion of notes are likely to be placed with investors rather than retained by the banks themselves as collateral for central bank repo transactions.

Positive signs

Fitch predicts the economic slowdown and tighter bank lending criteria will continue to limit asset origination.Nevertheless, there is little doubt that investor appetite remains strong, particularly among institutional investors searching for yield.

"There are not enough products for pension funds and insurers to invest in and securitisation products tend to produce higher returns," says Conor Downey, partner at international law firm Paul Hastings.

That demand is changing underlying conditions, says Mr Susini. Spreads in the primary market are tightening and prices are holding up in the secondary market, which are positive signs.

“The negative headlines [have been left behind] and there is a realisation that not all securitisations were bad and that some are very well structured products that have performed well. Banks are being encouraged to reduce their balance sheets so they are encouraged to issue securitisations. So, volumes may not be positive but there are indicators of improvement in perception,” says Mr Susini.

Demand pull

Strong investor demand, which could pull banks back to the ABS market, should come as no surprise given the strong track record of securitisations in Europe.

“Buyers have confidence because of the stable collateral performance of European ABS. The primary cautionary tale of the credit crisis relates to the perils, for all market participants, of highly leveraged, market value-based investing and the effect on valuations when vast quantities of leverage are suddenly withdrawn as occurred in late 2007, much of it having been sourced from the money markets,” says Mr Appen.

Those events precipitated a market value crisis, the dimensions of which, according to received wisdom, would inevitably be matched by a collateral performance crisis. Inconveniently for proponents of this view, including important parts of the European political or official sector, the promised meltdown in collateral performance did not arise.

“Rather, underlying collateral in the vast majority of European transactions continued to perform well, the structures were demonstrated to be sound and applicable ratings were upheld,” says Mr Appen.

Salim Nathoo, who manages the global securitisation group at law firm Allen & Overy, is of the same opinion. He notes that prime European securitisation deals have had a relatively low level of default, and have generally performed in line with expectations, unlike the US subprime market. “Investors are largely getting their money exactly as was foreseen,” says Mr Nathoo.

As a form of liquid secured funding with high ratings, the securitisations that do get to market will probably be oversubscribed, although growth may be slow.

“There has been contraction on the offer side, partly because there are fewer players and partly because securitisation is a financing product that is linked to the economic cycle. There are more deals in periods of growth but now there is less need for financing in general. On the demand side, in 2011 and 2012 securitisations were oversubscribed but overall there has been a slowdown in what was thought to be a recovery in 2011,” says Mr Susini.

Reticence among regulators

Post-2008 regulators were unanimously negative about securitisation, seeing it as irredeemable. Many feared it would be legislated out of existence. Nevertheless, a more nuanced view is emerging that distinguishes between the transgressions in collateralised debt obligations and the US subprime market and the broad stability of European ABS transactions.

The liquid asset criteria in the Basel liquidity coverage ratios will now widen to include some residential mortgage-backed securities, suggesting some regulators accept the importance of securitisation in bank funding. Yet proposed capital rules in Basel III and Solvency II could still dampen the appeal of securitised debt for banks and insurers.

"Securitisations are being treated less favourably than loans from a regulatory capital standpoint even on the same credit. So it is not a level playing field. Equality of treatment would be very helpful. Regulations keep changing and banks do not know how CMBS products will be treated,” says Charles Roberts, a partner at law firm Paul Hastings.

Some observers believe that regulatory uncertainty could ultimately give way to a better environment for the securitisation market. The initial knee-jerk reaction of regulators, exemplified by the first draft of the Solvency II directive, has been seen as extreme and the rules are now likely to be better calibrated, according to Mr Nathoo.

“There is government support in certain quarters for securitisation, which is seen as a valid tool for long-term funding. Securitisation is part of the UK government’s plans for funding infrastructure projects and there is a similar attitude in other parts of Europe,” he says.

All about transparency

One post-crisis priority for regulators was to improve transparency to give investors more clarity about their exposures. But UK Financial Services Authority and US Securities and Exchange Commission requirements for models on websites, in which investors can adjust variables, are as much about investor education as transparency. Indeed, some banks suggest that there is no more data they can give.

“Incremental transparency helps, but on the margin, since disclosure standards have always been high, if not completely standardised. Incremental transparency was assumed by many to provide a panacea to the faltering post-crisis market, although as subsequent events revealed, market recovery was not first and foremost a function of more transparency,” says Mr Appen.

In fact, it is far more important that securitisation structures are simpler. Since the financial crisis, the market has returned to the fundamental core of securitisation and away from pure financial engineering.

“The industry has made efforts to understand what investors expect so there are more straightforward products than before. Auto loans and credit card deals have always been there, residential mortgage deals are well established and there are attempts to restart the CMBS and collateralised loan obligation markets. Now, transactions are linked to the real economy. They are not about complex formulae and there are fewer tranches,” says Mr Susini.

Modern alchemy – the idea that poor-quality assets can be turned into high-quality securities “is a myth and that was the real core of the problem”, says Kevin Ingram, head of the London structured debt group at law firm Clifford Chance. Most securitisation structures worked, the issue was with particular types of assets in the US. European mortgage assets generally performed better than mortgage assets in the US, where the mortgage markets were less well regulated, Mr Ingram adds.

Raising standards

The market has made clear efforts to raise standards, such as the industry-led, non-profit prime collateralised securities (PCS) initiative launched in November 2011. PCS provides a label of quality, transparency, simplicity and standardisation for Europe’s ABS market.

So far, very few trades have been issued under the strict PCS eligibility criteria, the first being the Bilkreditt 3 deal, which was the first public Norwegian auto loans securitisation. PCS is generally viewed as a positive move, however, and its importance is likely to grow.

“We don’t have the full benefit of it yet, but we do see a positive impact from it on regulations – the improved treatment for high-quality mortgages and securitisations in the Basel proposals is a direct impact from PCS. Will it be a game changer? It may help, but it must be accompanied by regulatory change. It won’t be enough in itself,” says Mr Susini.

Mr Ingram draws a parallel with the South Sea Bubble stock market crash in the UK in 1719 to 1720, a scandal with one of the first joint-stock companies that saw calls for bankers to be locked in wooden chests and thrown into the Thames. That joint stock is now the most common form of ownership shows that the structure was not to blame, rather the way it was used. Securitisation, so recently labelled the cause of the financial crisis, is increasingly accepted as essential for fostering economic growth.

“The existential threat to securitisation has passed. In a Europe where the austerity dialectic is predominant, we have nevertheless seen that governments are unlikely to survive if they only prescribe austerity without trying to promote at least a vision of growth. In this context, securitisation is seen as a way to get finance into the real economy. So, ABS went from being the problem to being a possible solution. It is one of the few ways for banks to raise funds in a stress scenario,” says Mr Ingram.

It may be too early to talk of a full recovery in European securitisation, but for certain sectors there remains almost no other option. Cautious optimism stems from the strong demand for simpler structures – even if primary issuance is scarce, trust in securitisation is slowly building. If economic conditions stabilise and regulators show more acceptance of the sector, momentum will almost certainly follow.