Borrower-friendly loan terms in 2006/07 will allow embattled companies to postpone debt restructuring despite tough conditions in 2008. But they might be wiser to engage creditors early, says Philip Alexander.

When the credit markets first started shutting down in mid-2007, much attention focused on large leveraged loans that leading global banks had been unable to syndicate. As the signs of economic slowdown multiplied, thoughts began to turn towards the heavily indebted companies themselves and the risk that they would not be able to secure refinancing or even to meet their repayments schedule.

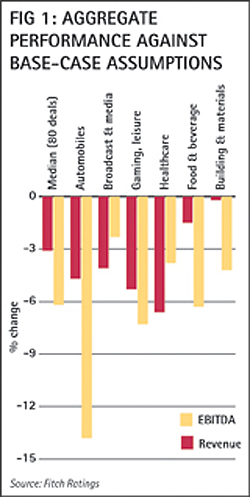

Already, many of the leveraged buyout (LBO) targets of 2006 and 2007 are underperforming the revenue and earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) assumptions of their private equity sponsors (see Fig 1 below). This makes it even less likely that they can obtain new funding for recapitalisation.

In a recent informal survey of mergers and acquisitions (M&A), leveraged finance and restructuring practitioners conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), almost half of the respondents were anticipating a 25% rise in debt restructuring in 2008 compared with the previous year, and about one-third were even more pessimistic, predicting a 50% rise. Significantly, however, only 32% thought that the liquidity squeeze itself would be the most likely catalyst for financial distress in UK companies – 47% pointed instead to falling consumer and customer demand.

Vulnerable to distress

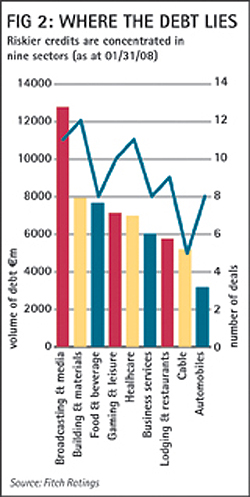

The most vulnerable candidates are those at which the two factors combine. Broadcasting and media is now a highly indebted sector (see Fig 2 below) that could be affected by the loss of advertising expenditure. Firms exposed to construction look set to suffer as property markets stall – especially in Spain, where the real estate slowdown is already entrenched. Sectors such as leisure, automotive parts and luxury food suppliers all face lower consumer spending. Many of these categories confront a further risk because global food and fuel prices have not corrected in line with equity markets and consumer demand. This leaves raw materials and transport costs obstinately high while revenues are falling.

The leverage in healthcare is also high but revenues should be relatively resilient to the cyclical downturn. However, Heather Swanston, business recovery partner at PwC, notes that the huge overhaul of procurement in the UK national health service makes visibility more difficult. Some private hospital chains have benefited but there could also be unexpected casualties if companies lose major nationwide contracts.

Higher leverage, fewer conditions

Another factor that is raising eyebrows is the unprecedented extent of leverage in LBOs, with debt-to-EBITDA ratios rising to “upwards of nine times” at the peak, according to Karl Clowry at law firm Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft in London. This is in stark contrast to a high of about five times leverage for the previous cycle at the start of the current decade. “In the past two years, bankers were under pressure to answer sponsors’ requirements for debt provision, people were competing to finance ever more aggressive structures,” says Mr Clowry.

Inevitably, this indicates lower potential rates of recovery for creditors where the borrowers are forced to restructure debt, says Pablo Mazzini, leveraged finance analyst at Fitch Ratings. His team follows about 280 transactions and he estimates that weighted average recovery rates for deals that closed in the fourth quarter of 2007 could be as low as 70%, down from 78% for the first quarter of 2006 vintage.

Other factors are also jeopardising recovery rates. According to Andrew Merrett, co-head of European restructuring at Rothschild in London, the more complex bank debt structures – divided into senior, mezzanine and subordinated debt tranches and second lien loans – that were previously employed only by the largest borrowers, have moved down to mid-sized companies.

Second, the proportion of at-risk transactions that took place across borders has risen, suggesting that a larger number of restructurings will take place in multiple jurisdictions. “You could have a holding company based in Luxembourg for tax purposes, a factory in Germany, Italy or France, and the debt documentation and capital structure based in London to access the capital markets,” says Martin Gudgeon, head of Blackstone’s European restructuring advisory group.

Blackstone advised Swiss flooring manufacturer Nybron, which closed a debt-for-equity swap late last year on debts of just €300m in five separate jurisdictions.

Mr Merrett warns that other mid-sized companies may not be so fortunate. “It gets much more marginal as to whether it is worth sorting out the complex capital structure and multi-jurisdictional issues versus using pre-pack insolvency to get the business out from under the structure,” he says.

A pre-pack insolvency involves the firm declaring bankruptcy and emerging almost immediately after a pre-prepared debt write-off and balance sheet restructuring plan, which may include its sale to another company.

Identifying impairment

Richard Nevins, a partner in Cadwalader’s financial restructuring department, helps clients to identify what classes of debt will have the relative position in the capital structure and legal rights to control the outcome of a restructuring. “If there is any impairment in a more senior class, such as the second lien, those creditors have the right to take the lion’s share of new equity relative to junior creditors, in return for writing off some of their debt claim,” he says. Cadwalader’s clients in last year’s restructuring of auto-parts producer Schefenacker were second lien loan holders who followed this approach quite successfully relative to the company’s junior bondholders.

In this cycle, there is a greater risk that value will break through even to the senior debt tranches because the competition for loan business in 2006/07 provoked increasingly lax cashflow headroom and performance covenants, together with ‘equity cure’ clauses that allow the sponsors to repair a covenant breach by injecting more of their own capital. Mr Clowry says this will stave off early creditor intervention even if company performance is clearly deteriorating. In addition, says Mr Mazzini, many 2006/07 vintage loans have a light debt amortisation schedule in the first three years into the transaction, which means the repayment hurdle in 2008 is not that high. Instead, any wave of LBO restructuring may be delayed until 2009 and beyond.

This does not mean the highly leveraged companies will escape unscathed, warns Ed Eyerman, head of European leveraged finance at Fitch. Heavy interest payments will reduce their working capital for investments, causing them to lose market share to rivals with stronger balance sheets. One example of this is UK retailer Debenhams, which was caught in 2007 with a balance sheet still leveraged following an initial public offering (after an LBO in 2003) and facing the revival of less indebted competitor Marks & Spencer. “Some of these leveraged companies may be ghost ships: they are becalmed at the moment, yet they are at risk of taking on water and they may not make it home,” says Mr Eyerman.

Vulture funds forced to wait

The markets are already beginning to price in this risk, says Mr Merrett, with stressed loans trading down significantly lower than the usual levels of 70 pence on the pound. “Traditionally, hedge funds would look for a covenant breach coming up and have a pretty well-known and low process risk for the restructuring. But now, by the time you get to exercise your creditors’ rights, that process risk could be higher and this has brought prices way down,” he says.

In these circumstances, distressed debt funds looking to buy into turnaround stories could have a long wait. Tony Lomas, business recovery partner at PwC, hears anecdotal evidence of a “wall of liquidity” collected by the numerous investors who have been raising funds recently (see box below). “It seems that most of these funds are still unutilised, because there are few suitable transactions available yet,” says Mr Lomas.

Given how much money is currently chasing distressed assets, Simon Richards, chief investment officer for fixed income at hedge fund RAB Capital, is careful not to neglect opportunities in unstressed paper that has been indiscriminately discounted in the credit sell-off. “There are AAA rated CLOs [collateralised loan obligations] with no subordination trading at 90 or 95 cents on the dollar. This is not about default risk, it is about the expensive cost of financing.”

Similarly, the secondary market loan prices for French cement giant Lafarge – which is an investment grade credit – have apparently sold off to levels more in line with high-yield paper, on expectations of a construction sector slowdown. “This is probably because of small low-price trades in an illiquid market by hedge funds facing margin calls. But there is no covenant breach; on the contrary, the finances of that company look relatively sound,” says one financial analyst.

First-mover advantage

If even these relatively robust issues are trading at a deep discount, vulture funds that enter stressed credit positions very cheaply will be able to profit quickly without needing to wait for a full turnaround story. “Distressed debt investing used to be a long-term reflationary strategy but there is so much more that people can do now,” says RAB Capital’s Mr Richards.

That is bad news for the borrowers, says Matthew Prest, head of European special situations at Close Brothers. “Those funds that have bought in much cheaper will have less interest in rescuing the company than the par-lenders who were there at the outset,” he warns.

Louis Gargour, managing partner of special situations credit fund LNG Capital, suggests there could even be a domino effect in under-pressure sectors, generating numerous pre-pack insolvencies. At one stroke, this will help them to clear their balance sheet and restore competitiveness with less leveraged rivals.

“I strongly believe that this credit cycle has accelerated so quickly that there are a number of companies that will be forced into bankruptcy precisely because their competitors have been,” says Mr Gargour, and he is planning investment strategies accordingly (see box above). For borrowers, the alternative tactic is to engage early with creditors, rather than letting problems fester until a covenant breach occurs. Mr Nevins believes that companies with private equity behind them are more likely to take this active approach. “You are not going to be dealing with founding families saying ‘I can’t give up dad’s firm’. The private equity sponsors are professionals who will know if their bet did not pay out,” he says.

Potential breaches

Ms Swanston at PwC says that she already sees evidence of private equity firms identifying potential breaches a year or more in advance. “If it gets to an actual breach, they know the creditors will be tougher. So the sponsors will ask for a two or three-year covenant reset now, for a fee, because they know they could not get such good terms further down the line.”

Europe’s largest ice cream maker, R&R Ice Cream, is a recent example. The private equity owner, Oaktree Capital Management, moved rapidly to secure a relatively favourable deal based on the creditors allowing covenant waivers and equity cures, in return for injecting more of their own capital (in the form of a payment-in-kind loan), a small margin increase and an ‘early-bird’ acceptance fee.

“The longer the negative news flow drags on, the more time creditors have to organise and the worse the terms will get for the sponsors,” says Mr Merrett.

NEW SELLERS, NEW BUYERS

Just as the owners of troubled companies have changed, there will be new faces on the creditor side of the table as well. The largest new source of leverage came from collateralised loan obligations (CLOs), which were themselves bought by institutional investors. Richard Stables, head of European restructuring at Lazard & Co in London, observes that the behaviour of these relatively new structures (and their collateral managers) that have not previously been tested through a major credit cycle downturn will be unpredictable.

Matthew Prest, head of European special situations at Close Brothers, is anticipating that many CLOs may become forced sellers. “The rules around the CLO funds will not permit them to hold that debt, either because the market value falls below a certain level, because the ratings fall below a certain level, or because there is a debt-for-equity swap and they are not allowed to hold equity,” he says. Moreover, the introduction of Basel II is likely to encourage banks to accelerate their own sales of stressed or distressed leveraged loans if they can, to reduce the regulatory capital burden attached to these assets.

This leaves the field increasingly to dedicated distressed debt investors. Mr Stables emphasises that even this specialist group is quite diverse and will act in different ways. “Some have been set up by private equity funds themselves and have hands-on operational management experience – they can take ownership of a business. There are others who are smart credit traders or multi-strategy hedge funds, and they recognise that running a business requires a very different skill-set.”

As the syndicating banks have stepped back from the lending relationship – and in some cases have scaled back their own debt workout teams – restructuring advisers will have a greater role to play in co-ordinating the process.

DON’T FEAR THE CREDIT DERIVATIVES

The vast growth of credit default protection has prompted unease that creditors with hedged exposure will be less committed to saving troubled companies. There have even been fears that creditor funds might prefer to allow a bankruptcy and collect their credit default swap (CDS) payout immediately, rather than wait for a turnaround process.

But restructuring professionals who spoke to The Banker cast doubt on the thesis. “Some CDS documentation may specify that the protection is invalidated if the holder deliberately triggers a default, or discloses that they hold the CDS,” says Martin Gudgeon, head of European restructuring at Blackstone. He says that he has not yet seen evidence of creditor behaviour being influenced by the use of CDS protection.

Andrew Merrett, European restructuring co-head at Rothschild, thinks the prevalence of funds (rather than banks) among creditors makes it unlikely that there will be many negotiators who hold both a long debt position and a CDS. “What the hedge funds tend to do is short the debt by trading the CDS when a company is beginning to get into distress. When the debt pricing gets low enough to be attractive, they are out of the CDS as there is no point being long and short at the same time,” he explains.

Louis Gargour, managing partner of special situations credit fund LNG Capital, says the major appeal of CDS is to take positions even where no underlying paper or maturity exists. Late last year, he sold one-month default protection on struggling automobile manufacturer GM. There were no obligations maturing in one month, and he considered that the probability of the company declaring a default in that one-month period was much lower than CDS spreads suggested.

Given his expectation of relatively high default correlations in some sectors, he is also looking at credit derivatives to exploit that correlation. These include ‘first-to-default’ baskets, which pay out depending on the number of defaults among a selected basket of credits.