In 2008, as conventional investment banks faced huge losses, Islamic investment banks were heralded as the last bastion of conservative, lower-risk investment, insulated by prudent management.

Sharia-compliant investments were considered free from excessive speculation, backed by physical assets and shielded from direct exposure to what we have come to know as toxic assets. Overarching principles of risk-sharing and profit-sharing provided a mechanism to bolster confidence in Islamic finance as a viable alternative to conventional financial services.

However, as the financial crisis wore on, Islamic finance demonstrated that sharia principles alone could not guarantee immunity from asymmetric economic shocks within an integrated global financial community. Compared with conventional banking, the sharia-compliant investment industry has demonstrated resilience to rapid changes in the economic landscape, but has proved to be far from risk-free.

As market analysts, sharia scholars, regulators and government policy-makers have reviewed the developments in Islamic investment banking during 2009 and 2010, a less than ideal picture has started to emerge. The financial crisis has revealed a fundamental limitation in the way that sharia-compliant investment has been implemented by many financial institutions, focusing heavily on real estate and development projects. Islamic finance, like any other industry, caters to the preference of the customers it serves, which has led to a lack of diversification in the product portfolio of Islamic investment banks.

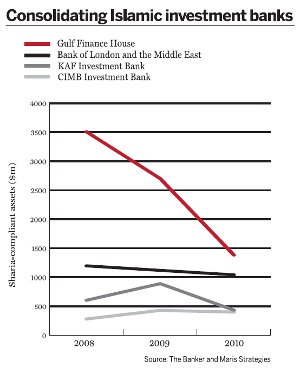

In previous years, many Islamic investment banks operated as small boutiques offering a limited portfolio of investments structured under sharia principles. As the global financial crisis developed, Islamic institutions encountered a reversal of liquidity, bringing the long-term viability of their business models into question. The lack of product diversification, failures in risk management and a preference for longer-term, illiquid investment have proved to be limiting factors.

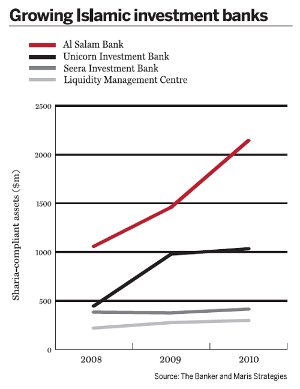

To correct these shortcomings, the industry will experience one or more of the following scenarios: consolidation (as boutiques are acquired by larger firms), redefinition (as current offerings are repositioned in larger sharia-compliant institutions) and/or an expansion of the product portfolio through co-operation with other Islamic investment banks or through white-labelling (rebranding) products generated by major global investment banks. Moving forward, Islamic investment banks will expand their product and services portfolio from infrastructure and real-estate financing to include asset management, brokerage services, corporate finance, private equity and project finance.

<strong>Sharia compliance risk</strong>

The crisis has also thrown up an entirely new risk unknown in the conventional sector: sharia compliance risk. The details behind the entanglement between Kuwait's Investment Dar and Lebanon's Blom Bank may set a legal precedent that starts Islamic investment banking down a slippery slope, from which it may take years to rebuild investor confidence. Investment Dar decided that $10.7m owed to Blom under an Islamic financing facility should be forced with conventional unsecured credit into Investment Dar's debt restructuring process. It did so on the grounds that the original deal was not sharia-compliant, even though the Investment Dar sharia advisory board had signed off the deal.

This calls into question the implementation and monitoring of Islamic product structuring. At the risk of oversimplifying a complex situation, the key lesson from this experience is not the fact that it had to be resolved through the courts, but that it has introduced a new element of long-term sharia risk to the risk-management equation in Islamic finance. Thus, Islamic institutions must now look to develop sufficient mechanisms to allay the fears of potential investors concerning any long-term risks linked with sharia-compliant investing. Sharia-compliant institutions must take three proactive steps: diversify the product portfolio, reaffirm the qualities and principles of sharia with mechanisms to measure each deal's compliance, and build the brand identity of Islamic finance.

<strong>Market opportunities</strong>

Fortunately, there are still numerous investors looking for sharia-compliant opportunities in the Gulf, north Africa and east Africa, in the form of investments in infrastructure. Gulf Finance House and the government of Tunisia recently announced a $3bn investment to launch the Tunis Financial Harbour. The sukuk market has also demonstrated a revival in recent months. France, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Malta, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Turkey have discussed the possibilities of debut sovereign sukuk issuance, which, if history is any indication of performance, would be oversubscribed.

As a new economic landscape materialises in the emerging markets, the future of Islamic investment banking has the potential to be exciting. Investment banks will be redefining their overall value proposition, portfolio of products, geographic reach and risk management strategies in 2011, which will open a new chapter in the provision of sharia-compliant financial services.