There is broad consensus that moving over-the-counter derivatives to central clearing will reduce individual and systemic risks, but this is not a panacea. Writer Philip Alexander

While the US Congress and European Commission (EC) may have discovered the virtues of clearing derivatives through central counterparty clearing houses (CCPs), financial markets first latched on to the idea after the collapse of Enron in 2002, when commodity derivative trades began to migrate to central clearing. And the fall of Lehman Brothers alongside the rescue of AIG just over six years later accelerated the trend.

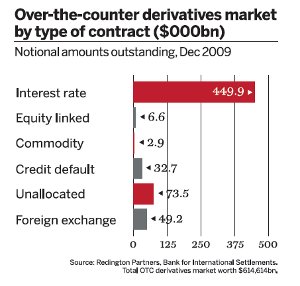

Most of the interbank interest rate derivative market clears through LCH.Clearnet, while the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) began clearing credit default swaps through its ICE Trust platform in March 2009. The largest dealers have already committed with their national supervisors to clear a certain proportion of over-the-counter (OTC) trades, and in total $200,000bn in derivative trades are cleared each year. However, the Dodd-Frank Act in the US and EC proposals published in September 2010 have changed the landscape in two significant ways.

First, policy-makers are intending to drive the maximum amount of derivative business possible, across all asset classes, onto CCPs - on a mandatory basis in the US, or by heavy capital requirements on non-cleared trades in Europe. Second, the legislation extends the reach of clearing from the interbank market to the banks' client base, capturing their bilateral trades with non-bank users of derivatives such as pension funds and asset managers. Richard Metcalfe, head of policy at the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), is encouraging market participants to put aside individual misgivings and focus on the systemic benefits.

"We want to bring people around the common point, which is that we are looking at clearing to improve the system's resilience overall. Of course, everyone has a fiduciary responsibility to their own shareholders to keep costs down. But they also have a broader responsibility to look at the system and say can we do things in a way that is more resilient, because that is also in their own self-interest - the two are not mutually exclusive," says Mr Metcalfe.

Buy-side concerns

The dealers readily acknowledge that the switch to central clearing for client business will push up costs for non-bank end-users. There will be a clearing fee, although each bank will have to make its own decisions about how much of that to pass on to its clients. And while most banks only request clients to post margin covering the mark-to-market price movement of existing trades - so-called variation margin - CCPs also require upfront initial margin, usually in cash or highly liquid instruments such as government bonds.

"We can customise what is eligible as collateral between counterparties. So for a credit portfolio, we could collateralise credit derivative trades with bonds that are already held in the portfolio," says Luc Leclercq, global head of operations, IT and projects at asset manager F&C Investments, which has more than £95bn ($148bn) under management.

By contrast, he says, the central clearing system has been designed for the interbank markets. Banks hold lots of cash as part of their normal functioning, but for pension and investment funds that are mostly invested in non-cash products, freeing up cash is a drag on performance.

To date, buy-side representation has not been as prominent as might be expected in discussions on the Dodd-Frank Act. At a round table discussion hosted by the two US derivatives regulators, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on August 20, BlackRock was the only fund manager to send representation. Matthew Kerfoot, a derivatives lawyer at Dechert in New York and former HSBC structured funds banker, has been advising buy-side clients on the SEC and CFTC process of drafting the rules to implement the Dodd-Frank Act.

"Dodd-Frank was not written with much specificity, so you can have a whole mosaic of viewpoints on what each provision means. So the buy-side can still have a significant say because there is so much still to be determined in the rule-making process," says Mr Kerfoot.

Richard Metcalfe, head of policy at the International Swaps and Derivatives Association

Open access

One subject on which participants have sought to influence the process is over access to the existing CCPs. This formed a major part of the August 20 discussions in the US. ICE Trust and LCH.Clearnet have tough requirements for would-be clearing members, including minimum capital of $5bn and substantial trading desk capabilities to provide actionable pricing. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Clearport requirements are lower, with minimum capital of $500m.

Asset managers are concerned that a low number of clearing members will limit the portability of trades in the event of a clearing member defaulting - in other words, the ease with which investors can transfer their existing positions to another clearing member.

ICE in particular has just 13 of the leading broker-dealer banks as its members in the US, with one extra (Société Générale) in Europe. LCH.Clearnet has more than 30 SwapClear clearing members (24 individual banks), but CEO Roger Liddell says the CCP is entirely open to taking on new members, and expects the list to hit 40 in a year.

"The SwapClear member requirements have not changed since the service was introduced more than 10 years ago. That might mean that what were high hurdles then are now much lower, because the business has grown so much. But we are now looking at membership requirements with more intensity. We would still need to be comfortable by some mechanism that clearing members who wanted to clear on behalf of their clients had the proper risk management capabilities to cope with a default by their client," says Mr Liddell.

The debate in the US came to the boil over an amendment to Dodd-Frank introduced by representative Stephen Lynch, which proposed limiting individual ownership in any CCP to 20%, to prevent incumbent owning members obstructing new entrants. The amendment was dropped, but a group of brokers and other participants who either wanted to become clearing members, or to win fairer access to CCPs for execution-only brokers, formed the Swaps and Derivatives Markets Association (SDMA).

Its founding members, including Jefferies, State Street and Cantor Fitzgerald, felt that ISDA was too much a creature of the incumbent dealers on the derivative CCPs. SDMA members believe the dealers have dominated the CCP risk and governance committees and obstructed new members to protect their own revenues.

The group secured a 'Lynch-lite' pledge from the CFTC and SEC, which would enforce a firewall between the clearing and trading arms of the large dealers. This would theoretically prevent the dealer banks from herding clients between their execution and clearing businesses, and open up more competition for both activities, bringing down bid/ask spreads and fees for end-users.

The dealing banks in general are agnostic on whether the ICE and LCH capital requirements are excessive. But there is stronger feeling on the need for clearing members to be able to participate in the default management process for the CCP if another member goes down. When Lehman collapsed in September 2008, LCH asked other leading clearing members to take down more than 50,000 trades each in which the stricken bank had been a counterparty.

"In normal conditions, when nothing goes wrong, the smaller players can do the same job as the larger players. But you cannot have membership criteria that only work in the good times, there has to be some test of how members will perform in adverse conditions," says Gavin Dixon, head of business management for fixed income trading at BNP Paribas.

Nevertheless, there are some clear anomalies. NewEdge, the broker jointly owned by two of France's largest banks, is the second-largest futures clearer on the CME behind Goldman Sachs, but is not yet a derivatives clearing member of ICE or LCH. Gary DeWaal, general counsel at NewEdge, which is also an SDMA member, says there is no reason why clearing members with more limited trading facilities should not designate other parties to unwind trades in the event of a member default.

Actionable pricing is already available through settlement facilities such as the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) lists. And administrators in securities restructuring or receivership situations - for example, the default of structured investment vehicles in 2008-2009 - auctioned illiquid structured credit to bond market bid lists, drawing wide market participation. Similar lists could be used for derivative unwinds.

Mr DeWaal is relatively confident that US rule-makers have accepted these arguments, to avoid a situation where bilateral clearing through a small group of counterparties migrates to CCP clearing through the same small group.

"Regulators are pushing for openness, but market forces are pushing for it even more. Centralised clearing is already gaining traction, and volumes will develop even without new regulations. High prices and wide bid/ask spreads are not sustainable, transparency will dictate, and there will be many new entrants," says Mr DeWaal.

Mark Beeston, CEO of portfolio risk services at ICAP

Unexpected risks

There is a danger that opening up the clearing market might lead to too many players, rather than too few. This raises the awkward question of whether centralised clearing, while removing some existing counterparty credit risk, will create new risks.

Chief among these is the growing complication of managing derivatives positions and associated collateral. Clearing houses will not handle trades that are too exotic, or too illiquid. This is likely to apply to some sophisticated hedge fund trades, bespoke hedges for corporate, pension or insurance clients, or even just very long-dated vanilla derivatives that do not trade often enough for pricing purposes. On top of that, certain types of corporate client activity may have exemptions on both sides of the Atlantic.

There may be differences between Dodd-Frank rules and the eventual EU regulations. Already, clearing houses have different set-ups: in the US, end-users face the clearing house as a separate entity, whereas in Europe the clearing house members collectively shoulder liabilities in the event of a default. This could mean different capital and collateral requirements associated with the counterparty risk. In addition, the EU has shown some willingness to provide a government backstop guarantee for CCPs given their growing systemic importance, but Dodd-Frank legislators were absolutely set against creating a whole new 'too big to fail' institution.

"There is an expectation that there is a benefit to consolidating from multiple bilateral relationships into a centrally cleared relationship. But there could be more fragmentation. Where we had a set amount of counterparty relationships repeated for each client, there could now be fragmentation by where your client is, which clearing house operates there, among clearing members to ensure sufficient portability of trades in the event of default, and between cleared and non-cleared trades, by instrument or by exempted client," says Jacqueline Walsh, head of the derivatives development group at F&C.

Managing the remnants

The residual trades that cannot be centrally cleared are one of the most pressing problems. Given their illiquidity and exotic nature, these trades are inherently more risky than the plain vanilla deals likely to migrate to central clearing. This means the bilateral OTC market will keep a residual risk larger than the volumes might suggest. At present, counterparties that enter into ISDA master agreements and credit support annexes (CSAs) to manage collateral in their derivative trades typically net out all the trades they have in place before calculating collateral posting needs.

"If you have hedged trades under a CSA with a certain counterparty at present, and you start taking vanilla parts of the portfolio out for central clearing, there is a chance you will increase residual risk under the CSA as well as taking on risk from the CCP," says Mr Dixon at BNP Paribas.

Mark Beeston, CEO of portfolio risk services at ICAP, is focusing on how participants will handle OTC derivatives that are too complex to clear centrally. ICAP has evolved from its original brokerage activities, and now owns a series of subsidiaries related to post-trade processing, such as electronic reconciliation services, transaction netting and collateral messaging and exception logging.

"CCPs bring a defined risk mitigation ladder. The question is, can the market replicate this for those trades that remain bilaterally cleared. The answer is yes, but so far this has been done manually and inconsistently. The market needs to automate processes for recognising that a trade exists, and agreeing a price to calculate collateral requirements - effectively the introduction of electronic affirmation and exception management tools," says Mr Beeston.

ISDA guidelines are gradually tightening, reducing the timeframe for resolving disputes over derivative prices and amounts of collateral that should be posted accordingly. Most recently, the organisation has advised that, where a price is disputed, the agreed collateral amount should be posted immediately, so that only the collateral equivalent to the difference in valuation between the two counterparties is delayed until the dispute is resolved. Minimum trade limits are also being driven down, pushing counterparties to manage collateral on smaller, more frequent trades.

Paul Wilson, head of client management and sales for financial and market products at JPMorgan Worldwide Securities Services, believes the growing complexity and demand for more frequent pricing and dispute resolution will drive many buy-side participants to outsource collateral management entirely. About 75% of his clients also make use of the group's third-party valuation services to help reduce and resolve disputes.

"The CSAs have become more complex, while clients are adding more counterparties to diversify risk. So we are seeing increasing volumes across an increased number of counterparties. And as we look at some of the ISDA best practice recommendations, among many things there is a requirement to improve, for example, the frequency of reconciliations from monthly to daily," says Mr Wilson.

He even sees early signs that some of the smaller sell-side players are considering outsourcing collateral management. Traditionally, the banks have had sufficient volumes of business to justify their own in-house collateral functions, but the move to a CCP could change that.

"The existing exchange-traded business is fairly streamlined, whereas the OTC market is more complex. If much of the existing bilateral OTC business moves to a CPP and looks quite similar to the current exchange-traded market with some added complexity, then some banks may simply be left with the collateral process on the complex business, which could be only about 25% of the volumes, but with similar levels of cost," says Mr Wilson.