Increasingly confident that they have made the banking sector resilient to any future financial crisis similar to that of 2008, regulators are now turning their attention to shadow banking. But a very different approach may be necessary.

Here is the good news. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) believes the task of reforming the banking sector to prevent a repeat of the 2008 crisis is almost complete. In a letter to the finance ministers of the G20 nations in February 2015, FSB chairman Mark Carney wrote that “much of the capital framework is complete and large, internationally active banks are on course to meet the new Basel III capital ratios almost four years in advance of the deadline”.

Here is the not so good news: the FSB is trying to work out where the risk from the banking sector has migrated. The answer, in essence, is into the shadow banking sector – bond markets, and the investment funds that dominate them.

“While the trend towards greater market-based intermediation through asset management entities is welcome and should contribute to the overall resilience of the financial system by providing alternative sources of funding, it is important to ensure that any financial stability risks are properly understood and managed,” the FSB concluded after a plenary meeting in Frankfurt in March this year.

Deleveraging concerns

At the heart of these new concerns is the sharp deleveraging of fixed-income inventories by investment banks. Previously, banks acted as a shock absorber, willing to buy assets from institutional investors even in declining markets, in the expectation of finding other buyers and profiting from any market rebound.

Basel III capital rules, including the leverage ratio, restrict the total size of bank balance sheets for a given level of capital. This has forced banks to cut back on bond inventories and on securities financing transactions that also helped maintain liquidity in the bond markets. In a February 2015 speech on market-based finance, European Central Bank vice-president Vitor Constancio emphasised that the risks posed by shadow banking should not be understated, because of its interconnectedness with the regulated financial system.

“If, for any reason, shadow banks experience substantial redemptions, they may be forced to promptly sell assets to fulfil their obligations, which may give rise to fire sales. This is particularly worrisome, since 98% of almost 95,000 non-money market investment funds operating in the euro area in 2014 are open-ended funds, which means that the investors can redeem their shares in the funds at any time. Moreover, the funds’ buffer of liquid assets that can absorb the equivalent of a run on shadow banks has dropped in recent years, increasing the illiquidity risks,” said Mr Constancio.

The specific reason for sudden redemptions that is clearly uppermost in the minds of regulators is the possibility of a turn in the US interest rate cycle. The Federal Reserve has not raised rates since 2006, but is widely expected to do so at some point during the next 12 months.

“No economist or market participant can tell with any certainty what is going to happen when interest rates rise. We can make historical comparisons, but there is no precedent for the scale of central bank activities such as quantitative easing. Spreads will widen, but if traders believe they can make money, they will return to the market,” says Werner Bijkerk, head of research at the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (Iosco).

The thinking among regulators is that they should try to build market resilience before the potential external shock. At its board meeting in South Korea in February 2015, Iosco established a new mandate to examine secondary market liquidity.

“There is a collective action problem that international organisations will need to address: the solution requires many people around the table, including both securities and prudential regulators, market-makers, trading platforms, investors and issuers. The good news is that there should only be winners from establishing liquid, well-functioning markets with smooth price adjustment to real economic shocks, but it will need leadership. Market participants may step up, or the authorities may need to introduce new rules,” says Mr Bijkerk.

Scale of the problem

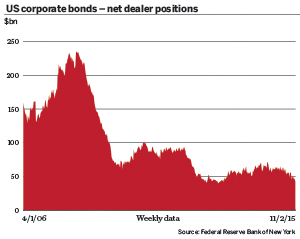

Federal Reserve Bank of New York data shows that net corporate bond positions among dealers are down by more than 80% since their peak in November 2007, at less than $45bn (see chart). And yet, most transactions are still taking place through the dealers. Research published by capital markets consultancy GreySpark Partners in March 2015 suggests that 57% of US and 44% of European corporate bond market turnover is controlled by the top five dealers in each region, with the top 20 controlling more than 80% of turnover in both regions.

But beyond the most liquid government bond issues, the investment banks are increasingly trading on an agency broker basis, matching off trades between clients rather than warehousing risk. Stu Taylor, the chief executive of bond information network Algomi who previously launched the market’s first fixed-income systematic internaliser trading engine at UBS, says only about 1.5% of the bond market is truly liquid.

“Beyond about the top 4%, liquidity drops off very steeply, and investment banks are now reluctant to put the balance sheet to work,” says Mr Taylor.

Algomi’s Honeycomb network, launched in 2013, is designed to provide brokers with a workflow to identify potential matches for trades right across the bank in multiple locations. Mr Taylor says there is growing interest from the buy-side as well, because the Honeycomb network will enable investors to identify discretely which banks are likely to be able to distribute the trade.

“The buy-side is facing a new dynamic because of the agency broker model at the big banks. Before, investors could request firm quotes from four or five banks who would offer to warehouse the risk. Now, many banks will refuse the trade, after having called other clients in an attempt to find a natural buyer, so there is much greater information leakage into the market,” says Mr Taylor.

New ways to trade

Given that investment funds now hold the bulk of bond inventory, buy-side firms also have a natural interest in exploring the potential to trade with each other rather than relying on dwindling dealers to act as intermediaries. There is a growing number of electronic trading platforms offering all-to-all trading. One of the entrenched players is MarketAxess, which launched its Open Trading system in 2012. This allows anonymous all-to-all trading. Participants can create watchlists of assets in which they are willing to trade, and will then be alerted as soon as a potential counterpart enters the market.

“Open Trading cannot create liquidity or replace the role of dealers as the dominant shock absorber during episodes of market tension, but it can create connections to aid liquidity such that all market participants are made aware if other risk-takers such as hedge funds are willing to provide liquidity opportunistically. Previously, funds could only do that if a dealer was aware of their intentions,” says Richard Schiffman, the Open Trading product manager at MarketAxess.

Transparency is also the primary concern to buy-side firms. Ideally, that means firm order posting – market participants knowing they are able to trade bonds at displayed prices, as is the case on a stock exchange. Alastair Brown, a former equities algorithmic trading specialist, is now seeking to do just that with his challenger all-to-all platform, OpenBondX. This is rolling out during 2015 with an enhanced request-for-quote system, in which participants will be obliged to post firm prices without backing away. In a second phase, he hopes to launch a central limit orderbook of the type that usually exists only on stock exchanges, with a view to attracting algorithmic trading.

“There are a vast number of issues for each individual name in the bond market, so you cannot ask participants to a make a market in all of them all of the time. What we have designed is a solicitation for price improvement that will route live orders anonymously to other participants. That will alert their trading algorithms and they can either fulfil the order immediately, or it will return to the orderbook,” says Mr Brown.

New platforms alone may not be enough. David Bullen, an independent electronic trading and market structure advisor who was previously a managing director of rates and credit e-commerce at Citigroup, says asset managers need to think differently about their own inventory to boost market liquidity. And they have good incentives to do so. When selling a bond to the buy-side, the best practice for bank sales-traders is to ask at what price the portfolio manager might be willing to offload that bond in the future.

“The dealing desks of buy-side firms need to think the same way, and ask their portfolio managers what sub-section of their assets they would be willing to set aside and at what level, and put those out as reverse quotes to form a depth of market. Once prices approach those levels, they could firm up. The more they provide the market with access to their inventory and their intent, the more they could bring down their own cost of execution and slippage from their performance benchmark,” says Mr Bullen.

Regulators muscle in

The desire for buy-side firms to build their own solution to the problem of market liquidity is intensifying, because if they fail, regulators are rapidly stepping in to fill the void. The question of whether and how regulators should tighten their grip on shadow banking partly comes down to a discussion about the existence of what Iosco has called phantom liquidity – a mispricing of liquidity risks by market participants.

A working group of the Basel Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) investigated the existence of this liquidity illusion in a report published in November 2014. Denis Beau, the director-general of operations at the Banque de France and chair of the CGFS working group, acknowledges that “gauging the beliefs of market participants from market data is obviously very challenging, and will never be fully possible”. Nonetheless, the group found evidence of relevant signals by combining market data and intelligence.

“The compensation that investors receive for bearing liquidity risks has fallen below its long-term average in major corporate bond markets, although remaining above the levels observed before the global financial crisis,” the CGFS reported noted.

Mr Beau says that regulators have no “silver bullet to dispel liquidity illusion”. But he sees potential in regulatory action on market microstructure, mainly as a means to improve transparency.

“In particular, pre- and post-trade transparency requirements regarding ticket sizes, trading venues and market-makers can provide investors with a set of valuable information, enabling them to take into account liquidity risk more accurately in their risk management,” he says.

He also emphasises the role of supervision. With the bulk of bond inventories now held by asset managers rather than banks, that process of surveillance may need to extend beyond the banking sector.

“Stress testing is one supervisory tool that can help market participants – and hence authorities – to have a better grip on their own resilience to liquidity risk and mitigate possible channels of contagion. And to have a system-wide perspective, liquidity stress testing should be conducted not only by banks but also by their counterparties, including fund managers,” says Mr Beau.

Joanna Cound, the European head of government affairs for $4650bn US asset manager BlackRock, told a Financial Times conference in March 2015 that large asset managers already deploy many of the tools needed to assess and tackle risks such as those posed by reduced bond market liquidity. These include stress tests akin to the banking sector and controls on leverage levels and counterparties, and on liquidity and redemptions.

“We use fund structural techniques such as swing pricing or bid/offer spreads so that the transactional costs are passed to the redeeming fundholder to take away any first-mover advantage for redemptions, and the suspension of redemptions or redemptions in kind. Some of those are for use in very extreme circumstances, so we also look at the mix of client types to forecast redemptions on a normal day-to-day basis and then layer liquidity in the assets to match those profiles,” said Ms Cound.

Systemic asset managers

The FSB wants more power to oversee these processes, however. In particular, a joint FSB and Iosco working group produced a second consultation in March 2015 on the criteria for identifying non-bank, non-insurance systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) that would be subject to enhanced supervision. This followed a first consultation in January 2014 that prompted 47 responses from the industry, many of them questioning the entire concept. After completing the designation concept, the joint working group will then consider what policy responses are suitable.

Under the proposed designation process, entities must first form part of an assessment pool, which is still based primarily on the size criteria used in the first consultation – funds with $100bn or more of assets. Consequently, while the consultation includes other entities such as hedge funds, non-bank finance companies and securities brokers as potential SIFIs, the US mutual fund industry believes its largest members are the most likely to face designation.

Dan Waters, managing director of ICI Global – the international arm of the US Investment Company Institute – estimates that about 14 large individual funds will potentially be designated. In addition, the designation could affect five or six independent asset managers and some bank-owned asset managers that are already covered by bank rules. Mr Waters accepts the need for as much data and understanding as possible on systemic risks in asset management. But he does not believe that SIFI designation is the right way to proceed.

“We very much support the work that Iosco and other regulators have been doing on systemic risk in capital markets. Let us have the discussion to understand what market-wide risks are there. That is the right framework, and we are very concerned that the entity question is going to cause us to miss the right analysis,” says Mr Waters.

This argument seems to be gaining traction in the US, where securities regulators in the form of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) are increasingly clashing with the stance of prudential regulators, specifically the Federal Reserve whose governors sit on the FSB. Two SEC commissioners, Michael Piwowar and Daniel Gallagher, have both openly criticised the FSB’s non-bank SIFI designation process during 2015.

“The repeated attempts of the FSB to characterise asset managers and their activities as systemically risky is nothing more than a ploy to wrest control of a hugely important sector of the capital markets from the SEC. For prudential regulators, this is about regulatory power and jurisdiction. The ideologues who are cheering them on do not mind making capital markets participants into public utilities like the too-big-to-fail banks,” Mr Gallagher said in a speech in April 2015.

Size versus activities

This is not quite the whole story. The non-bank SIFI designation process is a joint effort between the FSB and Iosco, and as such securities regulators have played a significant part in its drafting. None more so than Natasha Cazenave, the deputy head of regulatory policy at France’s Autorité des Marchés Financiers and the newly appointed co-chair of the workstream on non-bank, non-insurance SIFIs. She says the industry responses to the first consultation have been taken on board. In particular, the new methodology includes an extensive matrix of specific activities that should be used to judge if the non-bank is systemic.

Ms Cazenave cautions against using the term 'systemic risk' too loosely – it should not be applied to any spillover risk or investor protection concerns, but only to risks that could cause broad disruption in the financial markets and potentially into the banking system as well. The working group recognises that an asset manager acting purely on an agency basis could generally be wound down without much wider market disruption, regardless of its size.

“That is the purpose of the activities criteria, to make a qualitative regulatory assessment of whether the entity undertakes any non-standard activities that could pose wider risks in the event of failure, such as providing critical services or guarantees,” says Ms Cazenave.

Nonetheless, she says the pure size criteria for the assessment pool is still needed. This has also been modified to reflect the diversity of the asset management industry. For instance, a fund can now be placed in the assessment pool if it exceeds both $30bn in assets and three times leverage, to better incorporate leveraged hedge funds in the methodology.

“We are trying to identify an entity that potentially in itself, in case of stress or failure, could cause disruption to the global financial system, so there has to be a dimension of size. That is consistent with the methodology for banks and insurance companies,” says Ms Cazenave.

The new consultation also seeks to address scepticism toward the idea of asset managers posing a systemic risk through the market contagion channel in the event of large redemptions and forced sales of assets. This idea attracted far more criticism than the FSB/Iosco attention to the counterparty contagion channel, which is measured in the second consultation by examining items such as non-cleared swaps positions.

“In the new consultation we have sought to tighten the narrative around the risk of a downward market spiral. That is partly why we have introduced the concept of a dominant player – if an entity’s holdings in a particular asset class are large relative to the size of that underlying market,” says Ms Cazenave.

Crucially, she emphasises that the framework is not designed in a way that could deliver a predetermined set of designated entities at the end. While Mr Gallagher and others might well approve if the methodology leads to no designations at all, the tone of FSB members suggests an expectation that some entities should be designated. Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen said in March 2015 that the Fed would seek to improve oversight of “other large and complex financial firms” aside from the banks. Ms Cazenave and her colleagues will have to navigate a narrow path to reconcile these differences of opinion.

“We are trying to do something that is meaningful and robust, so that there is no risk out there that has not been covered. That does not mean that there has to be someone designated; what we want is a methodology that can scope out entities that do not pose a risk, and make sure that if someone passes the threshold it is because they do pose a risk,” says Ms Cazenave.