Oil hedging on the rise

Airline companies used to be one of the only markets that hedged their exposure to oil. But with the steep rise in crude prices over the past five years, many more firms are following suit, and now sovereigns in emerging markets are doing the same.

At the end of April, a struggling oil refinery called Trainer, near Philadelphia, was bought for $150m in a deal that would usually have garnered little attention. But while the acquisition itself might not have been unusual, the buyer – a subsidiary of Delta Air Lines – was. The takeover made Delta the first airline to purchase a refinery.

Delta’s chief executive, Richard Anderson, says it was an “innovative approach to managing our largest expense” – fuel – and that it would allow the company to shave $300m off its annual kerosene bill, which rose to $12bn in 2011, or more than one-third of its operating costs.

Analysts were split over the merits of the deal. While some lauded it as a prescient way to manage risk, others felt Delta was foolhardy to think it could run a refinery as efficiently as an oil company. At the very least, the acquisition demonstrated just how seriously companies now take hedging their exposure to energy costs. Mr Anderson says that Delta believes Trainer will allow it to “tackle the jet crack spread [the difference in price between crude oil and refined petroleum], which you cannot hedge in the marketplace effectively”.

Rocketing prices

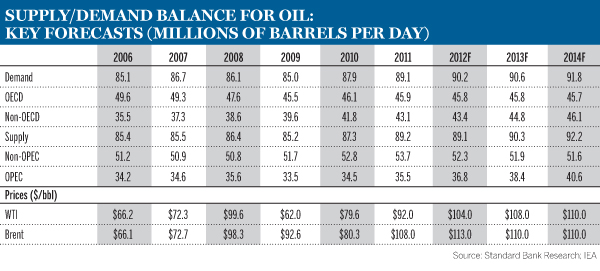

The growth of commodity risk management has in large part been caused by oil prices having risen so much in the past decade. For the first five years of this millennium, Brent crude prices barely went above $50 a barrel. Yet they edged up to an average of $66 a barrel in 2006 and $98 in 2008, according to Standard Bank. They fell in the following two years, but climbed again to $108 in 2011.

“The awareness of commodity risk exposure and how to manage it among companies that consume oil has increased significantly in the last few years,” says José Cogolludo, global head of sales and marketing in BNP Paribas’ commodity derivatives team. “Commodity prices and volatility have increased a lot over the past decade. Ten years ago, oil was about $10 to $20 a barrel. The rise since then has changed the dynamic of the market. Commodities have become a much bigger cost for consuming companies.”

Thierry Daubignard, global co-head of energy markets at Société Générale, says the number of firms wanting to use commodity derivatives has grown in tandem with the price of oil. “A few years ago, when oil prices broke $70 to $80 a barrel, more and more newcomers came into the market to hedge their exposure to increasing prices,” he says. “Small companies were in the past able to live with oil price volatility. Now, with prices over $100 a barrel, they have to carry out risk management.”

Oil demand robust

Some firms remain wary of financial hedging. They do not, after all, want to put in place derivatives that protect them against increasing prices, only to see those prices move in the other direction. But most companies are increasingly convinced about the merits of using hedges as a risk management tool. This is especially so considering global demand for oil should remain fairly steady over the coming few years, even given the crisis in Europe. “With global growth of 3% to 3.5%, this isn’t an environment in which the oil price is likely to collapse,” says Michael Lewis, head of commodities strategy at Deutsche Bank. “Demand is still relatively strong and supply is still quite constrained.”

When it comes to consumers in the private sector, airlines are among the most frequent user of commodity derivatives, as they operate in a particularly competitive sector in which fuel is by far their single biggest cost. As a result, they have been hedging for roughly two decades. “To this day, airlines represent up to 50% of hedging activity when it comes to consumers,” says Mr Cogolludo. “Jet fuel represents a significant part of their variable costs. To some degree they can pass on extra charges to passengers, but because of the strong competition in the sector this is tricky.”

With global growth of 3% to 3.5%, this isn’t an environment in which the oil price is likely to collapse. Demand is still relatively strong and supply is still quite constrained

Airlines are unlikely to slow down this type of risk management any time soon. Having derivatives in place can make the difference between a good and a terrible year for them. Virgin Atlantic said fuel hedges were a large part of the reason that it made a pre-tax profit of £68m (then $109m) in 2008, the same year that British Airways, one of its main rivals, lost more than £400m. Even airlines that used to be sceptical of derivatives are now frequently buying them. Low-cost carrier Ryanair, for example, disclosed in January that it had already hedged 90% of its fuel supplies for the first half of 2013. And Delta, which reckons it saved about $400m from hedging last year, says that its takeover of Trainer will complement, rather than substitute, its purchases of derivatives.

“Trainer will not limit our interest in hedging crude oil risk – indeed, creating 52,000 barrels of jet fuel daily will give us a better visibility about the jet fuel market and its pricing,” a spokesman told The Banker. “Being a producer will make us a more efficient hedger of fuel costs.”

Sticking with vanilla

A greater number of other types of companies are using commodity derivatives, too, albeit still to a lesser extent than airlines. Transportation groups, such as coach or shipping firms and industrial companies, which are usually heavy consumers of energy, are chief among them. Bankers say that even clients with indirect exposure to the oil market are speaking to them about ways they can hedge. Some road constructors, for example, use derivatives to cushion against a rise in the cost of bitumen, which is formed by distilling certain types of crude oil.

Most large-cap companies in Europe and North America that have turned to hedging commodity risks in recent years have been helped by the fact that they have long hedged their exposure to interest rates and foreign exchange (FX) rates. This enabled them quickly to familiarise themselves with the concept of doing the same with commodities. Mr Cogolludo says that as their risk management strategies mature, many move responsibility for commodity hedging from their fuel procurement to treasury departments, thus allowing for their hedging of FX, interest rates and commodities to be combined.

Despite their rising popularity, financial hedges used by consumers of oil typically have simple structures. Companies often buy swaps, whereby they set a price for fuel purchases with a hedging bank and, if spot prices rise above that, the bank pays them the difference. However, they lose out should spot prices fall below the swap price, in which case they have to pay the bank the difference.

To avoid the latter situation, call options are sometimes preferred. They let buyers set a ceiling for the price of their fuel while at the same time enabling them to benefit should prices drop below the level of the strike price. The main downside is that options, unlike swaps, require an upfront fee.

Bankers believe simple swaps and options will be favoured over complex products by the majority of companies. This is partly because they are easier to classify under accounting rules than exotic derivatives. They also generate less scepticism from stakeholders that lack financial expertise. “The bulk of hedging products are vanilla,” says Mr Daubignard. “The simpler the structure, the easier it is to explain internally, to stick to hedging accounting rules and to explain to shareholders.”

Commodity derivatives appeal

Recently, hedging activity has moved beyond the private sector to governments, who are also becoming more aware of the need to carry out commodity risk management, which can partly involve buying derivatives. “We’ve seen more net energy importers look to hedge oil prices over the past three years,” says Julie Dana, senior financial officer at the World Bank’s treasury and who advises sovereigns on risk management. “It is part of a much broader increase in interest in risk management.”

Like firms in the private sector, governments have been forced to manage their exposure to oil prices better in the wake of them rising so steeply since 2005. Europe’s financial crisis, and its effect on government bond markets globally, has merely heightened the need for such measures, not least for countries with high debt levels or importers that subsidise domestic fuel consumption. “With pressure on public finances, states are having to be more careful about how they spend their money, so they don’t want to have large exposures to fuel import prices, especially when they have to provide subsidies as well,” says Marc Mourre, vice-chairman for commodities at Morgan Stanley.

Despite this, very few countries make their oil hedging public. Mexico and Ghana are two of the select few that have done so. Mexico, a net crude exporter, uses put options to hedge against falling oil prices depleting its revenues. In 2009, these gave it the right to sell oil at $70 a barrel, far higher than the level of $30 the market fell to that year. Ghana, which became a crude exporter in late 2010, is the only African country to acknowledge publicly that it uses oil derivatives. It hedges itself both as a producer of crude and net importer of fuel, using call options for the latter.

Ghana and Mexico’s governments say hedging has enhanced their fiscal stability and boosted their standing among international investors, who typically have more confidence that a government will reach its revenue targets and be able to stick to spending plans should it use derivatives.

Ms Dana says that the two countries’ hedging programmes have not gone unnoticed by other emerging market states. “Because Ghana and Mexico went public with their hedges, many governments are asking a lot of questions about doing something similar,” she says. “The lesson from both of those countries is that it is important to use instruments that can be explained fairly easily to policy-makers and the public.”

Avoiding responsibility

However, plenty of states that want to start hedging are hindered by their lack of experience of derivatives. Often it is even unclear which ministry is responsible for hedging. The process is further complicated by it being politically sensitive, given the problems that arise for governments if the hedges, which are ultimately paid for by tax-payers, end up out of the money. “We’ve seen examples of countries that want to buy options but struggle to make a decision institutionally,” says Ms Dana. “The ministry of finance and ministry of energy might both want each other to set the strike price. Neither is prepared to make a decision.”

Commodity hedging can be used to manage short-term price movements. But it shouldn’t be used as a substitute for structural, long-term measures

Mr Mourre says that governments need to assess carefully which derivatives will be best for them. Options, which can be viewed as a form of insurance, are usually preferable for countries that want to have clearly defined liabilities. Others, however, might suit swaps more. “From a political point of view, it’s often desirable to employ a strategy which has a defined cost, and buying options is generally the best way to achieve that,” he says. “Using swaps, however, can be a good strategy for a country that doesn’t want to pay an upfront premium and can budget for a certain price for oil. But it’s important that they have in place robust control mechanisms to manage the process.”

Organisations such as the World Bank say that financial hedging should be just one part of a country’s overall commodity risk management. They stress that successful long-term strategies also depend on policies such as diversifying energy consumption towards renewable energy and natural gas. “Commodity hedging can be used to manage short-term price movements. But it shouldn’t be used as a substitute for structural, long-term measures,” says Ms Dana.

Market to grow

Many analysts think that while in the short term geopolitical risks linked to Iran and the Arab Spring could lead to a global squeeze in oil supplies, in the long run production is likely to keep up with demand. Seth Kleinman, Citi’s global head of energy research, says the dynamics of global supply have changed because of recent technological developments that have made it feasible to extract shale oil, the production of which is similar to that of shale gas.

Thanks in large part to shale oil, the US, which already produces about 1 million barrels a day of the stuff, is seeing its crude imports drop. “Shale oil is the real change,” says Mr Kleinman. “It represents a paradigm shift. The US is now the fastest growing oil producer in the world. US net import requirements are dropping by about 1 million barrels a day annually. That’s astonishing. Over the next three to four years, there’s the potential to get an extra 3 million to 4 million barrels daily out of the US. That’s dependent on prices and regulation, but it’s not an outrageous forecast.”

It is for such reasons – as well as an easing of tensions regarding Iran in the past two months – that investors are less worried about oil prices rising significantly than they were just before the market crashed four years ago. “In 2008, there was a 20% to 25% probability, based on options prices, that oil would hit $150 a barrel,” says Deutsche’s Mr Lewis. “Now, the market is pricing in a 7% probability of that happening. So there is concern, but it’s not as extreme as in 2008.”

Nonetheless, bankers reckon the commodity derivatives market will continue to grow, even if oil prices show little sign of rising in the near term. The volatility of those prices in the past four years has convinced many companies and sovereigns – both net consumers and producers – that risk management can no longer be ignored. “We expect that management of commodity prices – against both increases and falls – will increase in the next 10 years,” says Mr Mourre of Morgan Stanley.