Can the IPO market be reignited?

Turmoil in global equity markets has severely dented hopes that initial public offering activity would recover by the end of the year. But bankers insist that the market is still open and that just one successful, high-profile deal will lead the way for others.

If it was difficult to complete initial public offerings (IPOs) in the first half of this year, the final six months of 2011 are likely to be even tougher.

After the FTSE 100 had fallen 9.8% in the first week of August, the Standard & Poor's 500 7.2% and the Hang Seng 6.7%, bankers began to have serious doubts about the immediate future of IPOs across the globe. “We’ve had a cocktail of events that could shut the market for several weeks, maybe months, unless a catalyst event dramatically changes the current mood,” says Laurent Morel, head of equity capital markets at Société Générale. “The impact of the volatility will be very significant on the IPO market. It could be detrimental to the valuation of new stocks in the third and fourth quarters.”

Editor's choice

The fallout was immediately felt in the US and Asia, where, unlike Europe, there had been fairly high volumes of IPOs between January and June. China Everbright Bank delayed its $6bn Hong Kong offering, while container leasing firm China Shipping Nauticgreen shelved plans for a $193m listing. Ally Financial, a US car loans and mortgages provider, decided to put off a $6bn deal scheduled for late August.

From bad to worse

IPO markets were already fragile in late July, having weakened throughout the year amid concerns about eurozone debt, inflation in China and high unemployment in the US.

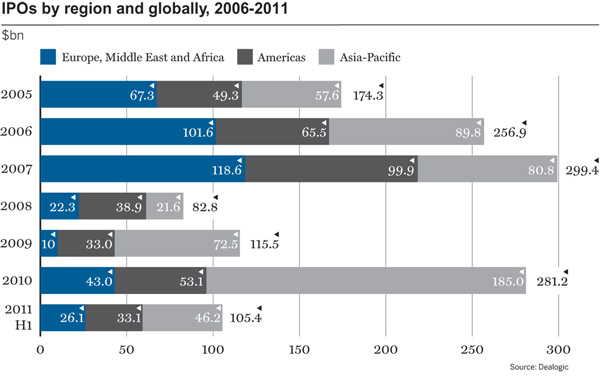

Europe had a torrid first half of the year. There were $26bn-worth of debut offerings across the continent, slightly higher than in the same period of 2010. But the figures were skewed by commodities trader Glencore’s $11bn listing, without which volumes would have been paltry. Moreover, several high-profile deals were cancelled or postponed. Among them were offerings of $2.6bn from Danish cleaning firm ISS and $1.3bn from Canal Plus France, a pay-TV company.

Asia and the US fared slightly better. IPOs in the former dropped 19% year on year, but still totalled $46bn between January and June. In the US, volumes tripled to $29bn, with many deals being increased and pricing above their initial filing range. But both regions, like Europe, saw plenty of deals postponed.

The slump in equities in early August – triggered by doubts about Italy and Spain’s solvency and exacerbated by Standard & Poor’s downgrade of the US – is likely to make vendors very wary about launching IPOs in September, if not before the end of the year.

It will also do little to ease the growing tensions, particularly apparent in Europe, between vendors, investors and advisors. Many potential sellers have criticised buyers for being overly cautious.

Investors reject this, accusing vendors of trying to attain bull market prices for their companies. Their rancour was summed up in late July by Tim Steer, a partner at UK fund manager Artemis. He wrote that the market "has deteriorated to the point where I now think of London IPOs as 'improbable price objectives'".

Buyers’ arguments have been supported by the poor secondary performance of several high-profile deals issued this year. Glencore’s shares, for example, had plummeted from £5.30 ($8.56) at the time they were listed in mid-May to £3.63 by August 9, a drop of 32%.

No trust

Bankers agree that the lack of trust between investors and vendors is a major problem, but doubt it can be restored while equity markets are so volatile. “There is a valuation disconnect between buyers and sellers,” says Nicholas Haag, head of UK equity capital markets at RBS. “We’ve ended up with a circular firing squad. Everyone is blaming everyone. It’s not a healthy situation.”

Long-only investors, traditionally the main buyers of IPOs throughout most of Europe, are especially anxious. As well as valuations, they have criticised the motives of vendors, and claimed that they often raise equity simply to exit at a high price rather than finance the expansion of their business or reduce debt.

The support of long-only funds is crucial to the European IPO market’s recovery. Hedge funds are too nervous to buy newly listed companies and are unlikely to make a comeback until the commitment of more traditional investors is clear. “During June and July, hedge funds were effectively absent from IPOs,” says Thierry Olive, global head of equity capital markets at BNP Paribas. “They weren’t buying anything.”

He adds that the few that are still interested in IPOs are asking for big discounts on what they perceive firms to be worth. “Even if they calculate a fundamental value of 100, they want to buy a company at 70 or 80,” he says.

The volatility in August led to almost all sectors of the equity markets falling heavily. Few were seen by share buyers as safe havens. Even the mining, defence and luxury goods industries, which analysts thought would be resilient, were hit hard, as investors fretted about another global economic slowdown.

Bulging pipeline

Despite the weak state of overall equity markets, the pipeline for debut listings is large. Many European companies had been expected to launch deals between September and the end of the year. Germany has several jumbo IPOs planned, including those of roughly €6bn to €7bn for chemicals producer Evonik and €3bn for Osram, a light bulb maker owned by Siemens.

Santander wants to list its UK business, while the Spanish government plans to sell part of Loterías, the national lottery company, in a deal that could raise €7bn. Russian companies, such as the mining companies Mechel and SUEK, are also considering selling stakes on western European bourses.

The queue for IPOs in Asia is also long. It is dominated by mainland Sany Heavy Industry, which sells construction equipment, and New Century Shipbuilding among them.

In the US, several technology firms are lining up to list. Facebook, which could be worth more than $100bn, is the largest. Others are Zynga, which develops online games, and Groupon, an online seller of discount vouchers.

A lot, if not the vast majority, of these firms will likely delay their launches until next year, say equities bankers. Most have the advantage of being able to wait, given that they have enough liquidity to service their debts and do not need cash imminently. This is true for private equity firms – which often use IPOs to sell companies in their portfolios – and corporate entities seeking to list non-core divisions, as is the case with Siemens and Osram. “There aren’t many forced sellers,” says Société Générale's Mr Morel.

“In most cases, private equity houses are comfortable. Their companies have good cashflows. Corporate firms aren’t in any kind of rush to spin off parts of their businesses via IPOs. Most have very positive cash positions. They can hold off for a while yet.”

Exits closed

Nonetheless, private equity groups might be forced to launch IPOs if they find that other exit routes are no longer open to them. In Europe over the past 18 months, sponsors have usually sold their companies to rivals via secondary buyouts, rather than by listing them. Yet the leveraged loan and high-yield markets – which are needed to finance secondary buyouts and had been resilient until early August – could effectively shut for the next few months, as they did in late-2008 following Lehman Brothers’ collapse.

Investors point out that problems in the market from that time also exist today, not least banks' rising costs of funds. “It will not take much for the leveraged debt markets to close,” says one. “If that happens, private equity won’t be able to exit through secondary sales. They’ll have to look at IPOs, even if the valuations they get aren’t to their liking.”

Equities investors will not necessarily jump at the opportunity, however. “IPOs will often be an exit of last resort for private equity houses,” says RBS's Mr Haag. “If investors realise this, they might be wary about buying them.”

But sponsor-backed IPOs have been among the best performing deals this year, which could persuade investors that they are worth the risk. Half of such IPOs issued in the US in the first six months of 2011 priced above their filing range, compared with 36% for non-private equity listings.

Sponsor-led IPOs have also traded better. Their median first day performance in the US between January and June was a 9.7% gain, whereas other deals rose 5.7%. A good early secondary performance is crucial for investors, particularly given their bad experiences with recent IPOs, including Glencore. “Historically, if an IPO doesn’t perform well in its first few days, it takes a long time to recover,” says Patrick Broughton, head of equities origination at RBS.

Cornerstones to the fore

With the market so fragile, bankers expect sellers that do attempt IPOs soon to be more conservative than in the past. As well as being less demanding over pricing, they are likely to use cornerstone investors more regularly. Glencore brought 12 in on its deal, including Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund; long-only investors such as BlackRock and Fidelity; and hedge funds Eton Park Capital Management and Och-Ziff. These investors, who committed to buying 30% of the offering, greatly helped Glencore raise what it wanted in the primary market.

Cornerstone shareholders, while difficult to use on small- and mid-cap listings, can play two crucial roles. First, they reduce the amount a company needs to place during an actual IPO. Second, they help when it comes to marketing a deal, especially if they are highly regarded, as was the case with Glencore’s anchor investors. “Some investors are followers,” says Mr Olive at BNP Paribas. “If they see that a high-profile fund manager has come into a deal as a cornerstone investor, they often think they should as well.”

Vendors and their banks are also likely to tap a wider group of investors, including retail accounts. In recent years, they have often been ignored because of the high demand from institutional investors. But deals such as Spanish lender Bankia’s €3.3bn listing in July – about 60% of which was bought by retail investors –have shown that they can sometimes make up for an absence of long-only and hedge funds.

In the UK, retail investors have not been a significant part of the IPO market for many years. But the London Stock Exchange is looking at changing that. Other parts of Europe have a stronger tradition of retail buying, especially when it comes to well-known brands. Loterías, which fits into that category, is therefore a deal bankers think could be launched even in a depressed market. “Loterías is one IPO that could succeed,” says Mr Morel. “Although it is big enough to need support from international investors, the strong retail bid locally would help a lot.”

Little at a time

Another trend expected to grow is that of companies only selling minority stakes. Trying to list all of a firm at once not only increases the level of equity that needs to be raised, but can also lead to investors questioning the reasons for the exit. Owners that sell only part of their company – thereby maintaining a stake – are less likely to be perceived as simply cashing in.

It is the volatility in the wider markets, however, that will ultimately decide how many IPOs are issued by the end of the year. Buying debut, unknown stocks is almost by definition riskier than investing in companies that have already been public for a while and that markets are familiar with. The risk is even greater when equities are performing as badly as they did in early August. “You can’t ignore the wider market,” says Mr Broughton. “IPOs tend to start happening in droves only when you get a long period of calm.”

Some investors are followers. If they see that a high-profile fund manager has come into a deal as a cornerstone investor, they often think they should as well.

The situation in the first half of August looked ominous for IPOs. Shares had not stopped their decline late into the second week, let alone recovered their huge losses since the start of the month. The VIX, a measure of volatility in the S&P 500, hit 48, a level not seen for over a year. “You can correlate IPO volumes almost exactly with volatility,” says Mr Haag. “When the VIX is above 25, then IPOs just stop dead in the US and Europe.”

Bankers and investors are loath to say the market is completely shut, however. They insist that IPOs, even jumbo ones such as Loterías’s, can still happen. They add that the occurrence of a single high-profile deal that prices within its filing range and trades up on its first day will give the market the boost it needs, and lead to more listings.

For others, IPOs are simply too important a part of global finance to stay in a slump for long. “The IPO market will recover,” says Mr Haag. “It is vital that it does, given it's in some ways the lifeblood of the financial markets.”