Europe draws on Japanese variable annuity experience

As companies abolish final salary pension schemes and governments seek to foster private pension provision, variable annuity offerings are moving to centre stage in Europe. But they require careful structuring.

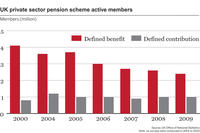

The defined benefit pension is an endangered species. As accounting rules force companies to plug actuarial deficits in defined benefit (DB) schemes, all but the hardiest of employers have chosen to close their schemes to new members. In the UK in 2000, there were 4.1 million active members of DB schemes but this had fallen to 2.4 million in 2009, according to UK Office of National Statistics data.

Worryingly, the alternative of defined contribution (DC) schemes do not appear to be picking up the slack. In 2000, there were 800,000 active members of such schemes in the UK, but this had only risen to 1 million in 2009.

Search for compromise

It is easy to guess what the reason might be. DC schemes do not offer guaranteed, inflation-adjusted payouts in retirement. Instead, the payout depends on the level of contributions paid in by each employee (and their employer if they are lucky), and the return on the assets in which the scheme invests. In the wake of sharp stock market falls during the financial crisis, the prospect of watching a DC pension pot being steadily eroded by poor returns is not particularly appealing.

But the implicit effect of this refusal to save for retirement is to place a greater burden on government to protect future generations of pensioners. Across Europe, government policy is heading in the opposite direction – looking for ways to bring down future state pension payouts to avoid a serious fiscal crunch. One possible answer is already long-established in the US market – variable annuity products that offer returns linked to investments on the upside, but provide a minimum payout guarantee to reduce the downside risk.

“A product that gives a mixture of income with a bit more growth and with downside protection is one that has inherent appeal. Variable annuities have been a very popular product in the US, but have not really taken off in Europe, possibly for reasons of investor education or product positioning,” says Robert Gardner, co-CEO of pensions consultancy Redington.

The successful variable annuity offerings have been fairly directed, with a small choice of funds and a simple menu of guarantees

Changing legal framework

That may be about to change, as investment banks and insurers are starting to plan offerings of guarantee wrappers for variable annuity products. HSBC has apparently offered a protection overlay on strategic allocations for whole DC schemes, but not yet a package for individual scheme members.

In the UK at present, individuals can invest in variable annuity products as part of their personal pension, or if their employer provides a group personal pension where the employer enrols staff and makes contributions into individual pension accounts managed by a third-party pension provider or insurer.

But there are still some legal hurdles before employers could offer such products to staff enrolled in an occupational pension scheme (where all contributions are paid into a single trust). In 2008, the UK government examined the concept of what it called “collective DC schemes” designed to provide the employer with the certainty of costs inherent in DC, but the employee with some predictability of benefits equivalent to the old DB structures.

“The employer pays fixed contributions into a collective fund instead of individual member accounts. The member is offered a targeted rate of pension based on the amount of money available from the employer’s contribution, and a targeted rate of revaluation,” says Andrew Block, a partner in the pensions team at law firm Travers Smith in London.

The added advantage here is that fees for structuring the investments to achieve the targeted revaluation rate would be charged for the fund as a whole rather than for each member individually. This is likely to work out much cheaper and therefore erode less of the members’ contributions. But the UK government opted not to proceed with legislative changes that would facilitate these schemes, even though the Netherlands has already authorised a similar system.

UK annuity move

On the other hand, the UK Finance Bill due to come into force in July 2011 has removed the requirement that pensioners must transfer their pension investments into a fixed annuity product between the ages of 55 and 75. Pensioners may not want to keep all the market risk after this age, so a variable annuity that offers downside protection with some continued growth potential may fit the bill.

“Forced annuitisation had its disadvantages, especially when we are about to see growing demand for annuity products as members are no longer offered DB schemes. As life expectancy is rising, individuals need to have the choice of continuing to invest some of their money in equities for growth after retirement, and using real estate or corporate bonds to provide an income component, and then annuitising at a later date,” says Mr Gardner.

Across the EU as a whole, one major challenge is the fragmented nature of pensions regulation and market practices compared to the US or Japanese markets. Occupational pension schemes are much more common in the UK, the Netherlands and Scandinavia than elsewhere. And there is no uniformity in the tax treatment of life insurance contracts, says Emmanuel Naim, head of variable annuity business for Société Générale Corporate & Investment Bank (SGCIB).

In Germany, there are tax advantages only if savers invest for at least 12 years and pay regular premiums, whereas in France savers need to invest for a minimum of eight years and regular premiums are not needed. This makes it difficult for insurers to propose the same products across all the countries of the European market.

Nonetheless, he believes the approaching implementation of Solvency II regulations for insurers may well provide extra momentum behind variable annuity offerings. This is because it will change the treatment of guarantees offered by insurance companies for unit-linked investment products. Under the earlier generation of insurer solvency regulations, only Luxembourg and Ireland had provided capital relief for insurers if they had reinsured or hedged their guarantee exposure.

“In all other jurisdictions, when insurers wanted to write guarantees on unit-linked products, they had to set aside a reserve of 4% [of the guarantee value]. Solvency II removes this constraint, in the sense that what counts is the economic match between the assets and liabilities of the insurer. So if they have implemented a properly matched reinsurance or derivative contract to hedge the guarantees, they could claim capital relief,” says Mr Naim.

Importing experience

In this regard, Solvency II will bring the EU more into line with Japan, where the variable annuity business has already become significant. Experiences in Japan and the US, both positive and negative, can provide structurers in Europe with an idea of how to manage the risks associated with a variable annuity offering.

“Insurers are now very well positioned to offer minimum guarantee products, and it is a high-margin business. But profits are backloaded – there are high costs to sell these policies via banks or agents, so they pay up-front commissions. That means the profit curve is quite negative for the first two or three years,” says Michalis Ioannides, head of insurance solutions at BNP Paribas in London.

Moreover, with the introduction of Solvency II, any risks that are not matched properly absorb regulatory capital for the insurer. Mr Ioannides believes this may drive some of the smaller insurers out of the variable annuity market. “But insurers who can adjust the offering a little, and are capable of managing this matching risk, can be winners from Solvency II. They will be willing to write more of this business,” he says.

Risk approach

SGCIB has already closed many deals to hedge variable annuity products for insurers. Although the market risks can be hedged through derivatives, actuarial risks arising from variations in mortality rates, or policies that lapse or are transferred when employees change jobs, require thoughtful product design.

“What matters is taking a statistical approach to non-market risks. This is the natural business of insurance companies, but now banks have evolved toward taking some of those risks, and we have been at the forefront of taking mortality and lapse risk since we created our own reinsurance company Catalyst Re, which can transfer the risks into the capital markets,” says Mr Naim.

Catalyst Re was originally created to reinsure variable annuity risk for US insurance giant Metlife in 2006, but has since seen growing volumes of business in Japan as well. Mr Naim says the key lesson from these markets is that to facilitate hedging or reinsurance the product range should not be made too complex.

“In Japan, the successful variable annuity offerings have been fairly directed, with a small choice of funds and a simple menu of guarantees. In the US, there was more tendency to offer a big range of underlying assets that units would invest in and many different types of guarantee. This may look good from a marketing viewpoint, but it can increase the risk of potential losses for insurers,” he says.