Saudi Arabia steps up its growth strategy

King Abdullah Financial District, Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia stuttered during the global financial crisis, but never plumbed the depths of the world's more developed economies. Now, as political unrest shakes its neighbours, the country's leaders are eyeing a more prosperous future, with a key focus being on educating and employing its youth and women. But will these spending initiatives deliver the growth the country badly needs?

Saudi Arabia, under normal circumstances, would be justified in feeling quite bullish about its prospects for the rest of 2011 and beyond. Oil revenues are strong, the banking sector is in relatively robust condition having come through the global financial crisis largely unscathed – except for the defaults involving the family dispute between two major Saudi companies, the Saad Group and Ahmad Hamad Algosaibi and Brothers (AHAB) – and the 2011 budget envisages a 7.4% increase in expenditure to a record SR580bn ($157.7bn).

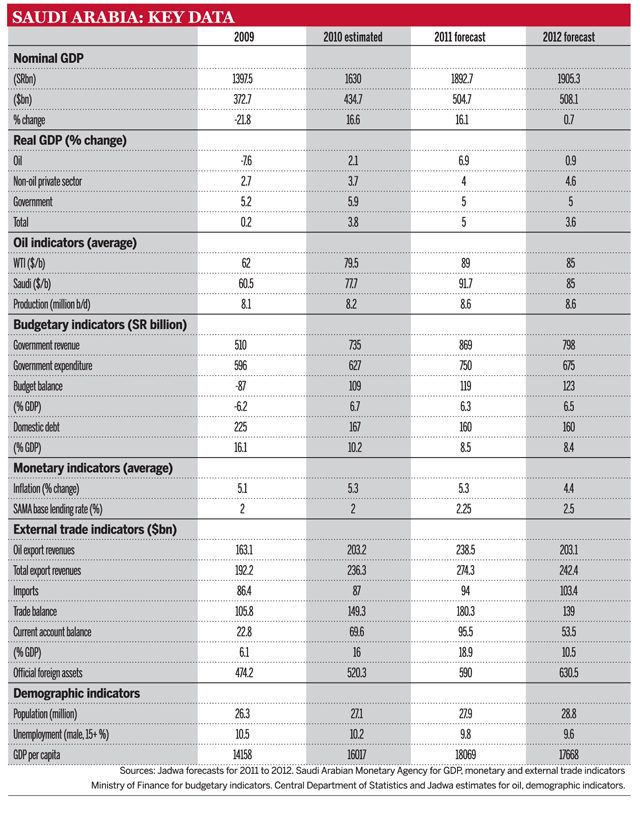

In contrast to many countries mired in deficits and spending cuts, the country had a substantial budget surplus of $29bn in 2010, was able to trim its domestic debt by six percentage points to a mere 10.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) and looks set to improve on last year’s recovery and 3.8% economic growth.

But these are not normal circumstances. The popular political unrest in the Middle East and north Africa (MENA) this year, that has seen the ousting of two presidents in Tunisia and Egypt and a civil war, in effect, in Libya, as well as turmoil in Bahrain, Yemen and Morocco, has changed both the political and economic climate in the region.

Turmoil effect

For Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter and one of the only global producers with significant extra oil capacity to cope with major oil shocks, estimated at 4 million barrels a day, the regional turmoil cannot be ignored. But while Saudi Arabia has similar demographics to the countries of north Africa, with 66% of the population under the age of 30 and high youth unemployment (an estimated 39% of Saudis aged between 20 and 24 are out of work), there are also considerable differences between the Gulf states and the countries of north Africa, and the region is far from homogenous in either political or economic terms. For example, with regards to GDP per capita, Saudi Arabia at more than $18000 considerably outperforms Egypt at about $3000.

It is also important to point out that the global financial crisis and the recent Middle East upheavals have amply shown that the views and forecasts of economists and political commentators can be completely wrong. Nevertheless, given that humbling proviso, it is worthwhile assessing the various dynamics surrounding the MENA region’s largest economy and its entrenched political culture.

In assessing the north African turmoil, concerns elsewhere in the world and the impact they are likely to have, John Sfakianakis, chief economist at Saudi Arabian commercial bank Banque Saudi Fransi, noted in early March: “Markets are beginning to price a shift of contagion from north Africa to some of the Gulf economies, principally Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. The possibility of contagion spreading to Saudi Arabia remains low although markets are pricing a higher risk premium. Bahrain’s future is a leading indicator but there is not enough clarity about short-term political outcomes.”

He added: “We remain reassuring about Saudi Arabia. The chances of disruption to oil production remain distant as is the likelihood of major unrest. Markets have a tendency to differentiate less during crises and, as we saw during the Dubai debt crisis in 2009, risk premiums spiked for all.” The conclusion here is that differentiation takes time and crises often lead to rushed ill-considered judgements.

Opportunities for the young

In political terms, Saudi Arabia faces key challenges in relation to creating jobs for its youth but, unlike Egypt, it has the funds and the will to address some of these problems. The country's budget dedicated to education spending has more than doubled since 2005 and the allocation for education and training programmes in 2011 amounts to 28% of the record SR580bn budget, or a huge $40bn.

Some of these vast sums are being spent on education specifically for women: projects such as the Princess Nora University in Riyadh which will have a capacity for 25,000 female students, for example. But the core challenge is meeting job expectations for the women flooding out of universities, those in education and the 100,000 male and female students currently studying abroad.

With the unemployment rate among the 18.5 million indigenous members of Saudi Arabia's population at a worrying 10%, and only one in 10 private sector employees a Saudi national, the country faces severe structural challenges. Talal Al Qudaibi, CEO of Riyad Bank, one of the biggest in the country, notes that banking is unique in that more than 75% of those employed in the industry are Saudis, with Riyad Bank boasting the highest percentage of Saudi-born workers at 93%. But outside the banking sector, more jobs for Saudis are desperately needed. While Mr Al Qudaibi notes that more Saudis are now willing to work in supermarkets and fast-food outlets such as McDonald’s, the Saudi employment rate of just 10% in the private sector is far too low and the Saudi bias towards creating government jobs is also weakening public sector productivity.

Finding a solution

So what can be done in the country to address these employment and social dilemmas? King Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz, returning from surgery abroad in late February 2011, outlined a huge extra $36bn stimulus package aimed at these issues which was deliberately targeted at lower income groups (see box). This, along with the record budget for 2011, demonstrates that the Saudi government is certainly willing to throw all it can into boosting its economy, creating jobs and satisfying its citizens' needs. But while economic growth in 2010 was 3.8%, following a sluggish 0.2% in 2009 and 4.2% in 2008, the key question to ask is whether growth of about 4% is enough for the country to achieve its objectives?

Brad Bourland, chief economist at Jadwa Investment, believes that while 4% growth may seem acceptable, it is inadequate for both the country and the Middle East at large. “The challenge for Saudi Arabia is to find policies that are growth-oriented to meet the economic aspirations of the people. The Middle East needs to grow at more than 4% and more like China and India if it is to reach its potential.”

Others complain that in spite of major government spending initiatives, up SR76bn or 13% of GDP in 2009, non-oil private sector growth only rose by 2.7% in 2009 and only reached 3.7% growth in 2010. Saudi Arabia does not appear to be getting the growth it needs from its huge spending initiatives.

Abdulrahman Al Hamidy, the vice-governor of the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), agrees. He says “The private sector needs sustainable growth and we probably need to have more than a 4% growth rate.” But how is this growth to be achieved? Mr Al Hamidy believes that creating new infrastructure, such as through industrial cities and new universities, is the way to sustainable growth, and he is also keen on encouraging lending to small and medium-sized enterprises and supporting the development of housing.

Industrial city template

Industrial cities started in Saudi Arabia in the 1970s in the petrochemicals sector and have had great success at the initial sites of Jubail and Yanbu. Today there are 17 industrial cities throughout the country involved in host of downstream industries. Industrial affairs deputy minister Dr Tawfig Fozan Al-Rabiah says that while the 17 cities account for 12% of GDP today, he expects them to account for 20% of GDP by 2020 and create many new jobs.

Mr Al-Rabiah, who is also director-general of the Saudi Industrial Property Authority, plans to expand the number of industrial cities to 30 over the next five years, thereby doubling the land for these expanding industrial developments to 150 million square metres. The country needs to diversify its industrial production, he explains, to create more value-added and more jobs.

Mr Al-Rabiah highlights a recent success with a SR500m agreement reached in February with Japanese truck manufacturer Isuzu to build 25,000 medium and large trucks a year at Dammam Industrial City 2. The project, on 120,000 square metres of land, will open up employment and investment opportunities in complementary industries, with 40% of the trucks expected to be exported. With Saudi Arabia investing $100bn every year and massive projects in the pipeline, such as $12bn with Saudi energy company Aramco and more than $16bn with US chemical manufacturer Dow Chemicals, Mr Al-Rabiah is confident that the expanding industrial cities can provide significant growth and employment.

Looking at 2011 to date, the MENA region has been destabilised by sweeping political unrest, and no one can predict with any certainty how events in a number of countries will play out. In Saudi Arabia, however, the country’s core financial strength (estimated official foreign assets at end-2010 are $520.3bn) and extra oil output capacity have acted as a steadying force in terms of oil production both in the region and across the world. The country's ability to raise production by 700,000 barrels per day in March to compensate for Libya’s shortfall, as well as King Abdullah's unveiling of an extra $36bn stimulus package to support lower income groups, clearly indicate it has the capability to calm some of the turbulent waters in the region and the will to continue to face the domestic challenges ahead.

KING ABDULLAH'S ANNOUNCEMENT

In a Keynesian approach to the current turmoil in the Middle East and north Africa, King Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz has unveiled a series of initiatives estimated to cost SR135bn ($36bn) to support lower income groups, bolster Saudi Arabia's housing industry and boost education.

The 19 new measures introduced by King Abdullah on February 23, 2011, to boost social benefits and increase debt write-offs also include the introduction of an unemployment benefit, the first of its kind in the country, providing wages for one year to jobless Saudis searching for work.

With higher oil prices and net foreign assets at the end of 2010 of SR1650bn, Banque Saudi Fransi chief economist John Sfakianakis says: “Saudi Arabia can comfortably finance social policies designed to ease the burden of high property prices and housing market imbalances, while helping its young population cope with a mounting unemployment challenge.”

As of 2009 there were 448,547 unemployed Saudis, giving the country an unemployment rate of 10.5%. Its unemployment benefit scheme is expected to be of most use to youth; joblessness among Saudis below the age of 30 was 27% in 2009, and stood at 39.3% for those between the ages of 20 and 24.

Private sector problems

The unemployment dilemma is a core national concern, with currently only one out of every 10 employees working for a Saudi private sector company being a Saudi citizen and the public sector no longer able to act as employer of last resort. In supporting the need for creating more jobs for indigenous workers, King Abdullah called for the formation of a committee of ministers to study the unemployment problem.

The initiatives offered by King Abdullah targeted not only unemployment but also crucial housing issues and education. He raised the General Housing Authority’s budget by SR15bn, while the Saudi Real Estate Development Fund (REDF) was given a SR40bn capital injection which is expected to shorten the estimated 18-year waiting period Saudis face to qualify for a loan due to pent-up demand. The government also plans to inject SR30bn of new capital into the Saudi Credit & Savings Bank, a specialised credit institution, and forgive a number of debts, thereby lending support to lower income groups. In REDF’s first 25 years, 22,000 housing units were built annually, but estimates suggest there is an annual need for more than 230,000 housing units each year.

In education, King Abdullah pledged to set aside SR100m for students in need of financial support, expand a state scholarship programme, and for state employees a 15% cost-of-living allowance over the past three years will now be made permanent.

In commenting on the collective measures, Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency vice-governor Abdulrahman Al-Hamidy says they will: “provide sustainable growth, create employment opportunities and make people feel there is fairness”.