The Banker's Top Islamic Financial Institutions – 2016

Having tracked the development of Islamic finance for a decade, the latest results in the The Banker's Top Islamic Financial Institutions ranking for 2016 reveal a sector that has enjoyed admirable growth compared with its conventional peers. James King reports.

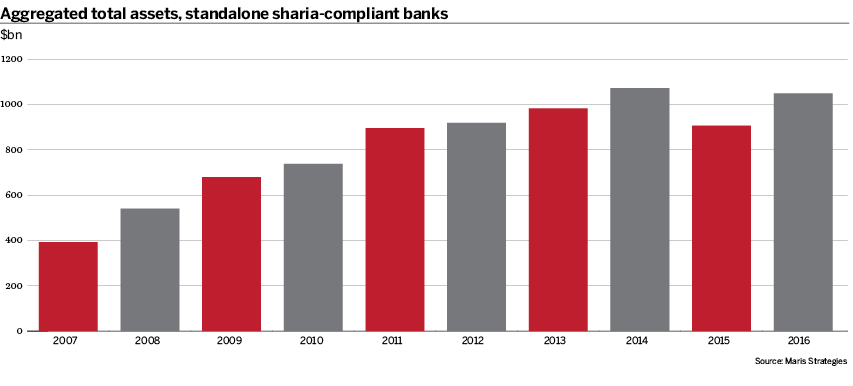

The 2016 Top Islamic Financial Institutions ranking marks the 10th year in which The Banker has tracked the performance of the global Islamic finance market. In that time, the industry has blossomed from a relatively small-scale, concentrated affair to an international market that is thriving in both developed and emerging economies alike. To put this transformation into perspective, in 2006 total global sharia-compliant assets stood at $386bn. A decade later, that figure has jumped to $1440bn, representing a compound annual growth rate of 12.72%.

Not only does this growth dwarf that of conventional institutions, it also points to the wider acceptance of Islamic finance by consumers, financial institutions, policy-makers and regulators during that time. Today, asset and profitability growth go hand in hand with the development of a flourishing ecosystem of players that is increasing the sophistication of this expansion.

“I think one of the reasons that we have seen Islamic finance grow so quickly over the past decade is that it has benefited from a supportive economic climate and it also proved it had something to offer. Islamic finance has an economic added value. Strengthening this will be important to maintain growth,” says Mohamed Damak, global head of Islamic finance at rating agency Standard & Poor’s.

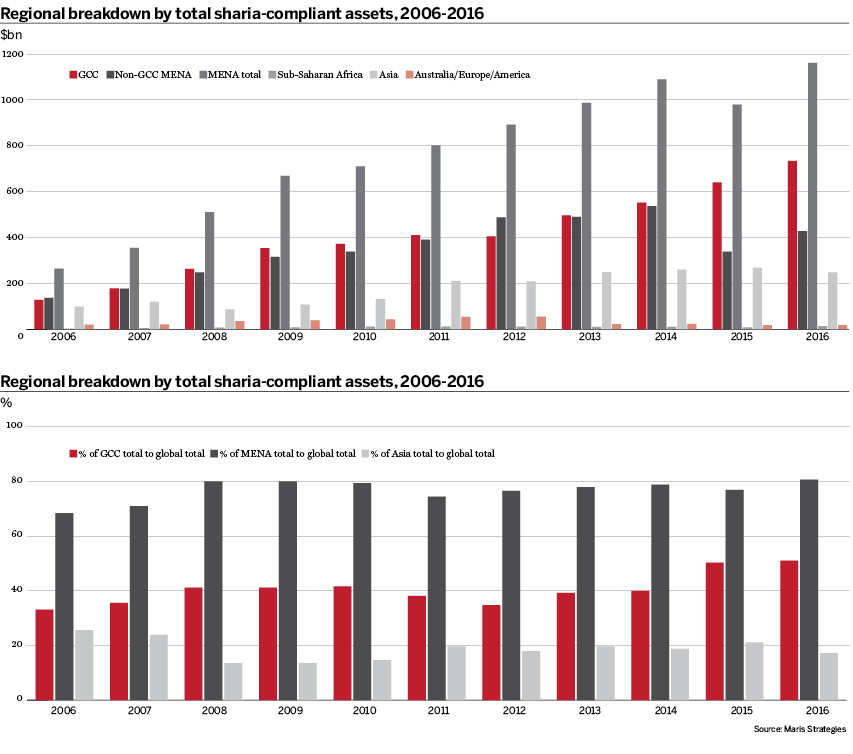

But this upward trajectory has largely been driven by markets in the Middle East and north Africa (MENA) region. As The Banker’s data shows, the percentage of global assets hailing from the MENA region was about 68% in 2006 survey, a figure that had climbed to 80% in the 2016 ranking. Conversely, the contributions of Asia, with most of these coming from the dominant hub of Malaysia, have fallen somewhat. In 2006 the region accounted for about 25% of total global assets. In this year’s ranking that figure has fallen to 17%.

Decade of change

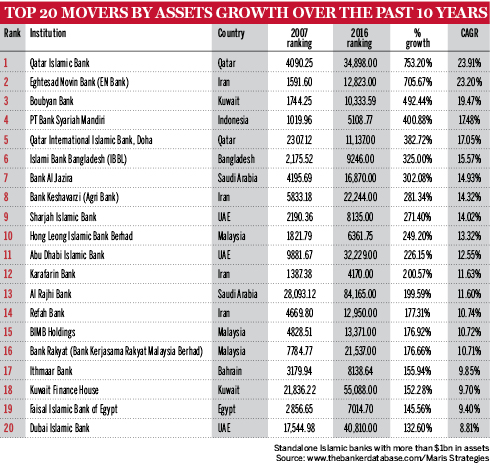

These trends are reflected in the table for the top 20 movers by assets growth over the past 10 years. Of the top 10 institutions in this table, seven come from the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) region or Iran, while only three from the Asia region are present.

But numbers alone do not tell the whole story. While the past decade has seen the industry’s total assets skyrocket, other changes have also been under way.

For one, the environment in which Islamic financial institutions do their business has completely transformed. Eager governments looking to tap into the potential offered by this nascent industry have introduced supportive policy frameworks and competent regulatory agencies to grease the wheels of business. Nowhere has this process been clearer than in Malaysia, considered by many observers to be at the forefront of the industry’s development.

Though it may lack the big pools of liquidity found in among the GCC countries, Malaysia has worked hard to develop the most business-friendly and progressive sharia-compliant operating environment in the world.

“Malaysia has successfully emerged as the world’s leading jurisdiction for sharia-compliant finance because the government is behind the idea and it has fostered a thriving ecosystem of private and public sector players. Other markets need this kind of backing,” says Dr Amat Taap Manshor, chief executive of Malaysia’s Finance Accreditation Agency (FAA).

But in terms of pure growth, the markets of the GCC are in a league of their own. Over the past 10 years, the GCC region has registered a compound annual growth rate of more than 17%. This compares with just 10% for the rest of the Middle East and 8.7% for Asia. High oil prices, an elevated proportion of high-net-worth individuals and rapid economic growth go some way to explaining this. Between 2008 and 2009 alone, the region’s total assets jumped from $262bn to $353bn, while the rest of the world reeled from the effects of the financial crisis.

Even as this wider growth story unfolded, the Islamic finance market was not immune from various global and regional pressures. In the 2015 ranking, the total assets of the industry fell for the first time – by 8.48% – as a number of key currencies reduced in value against the dollar.

Indeed, pressure has been mounting over the past two years as prominent markets in oil-exporting economies have had to contend with a lower commodity price environment and the rationalisation of all-important government expenditure.

Tougher conditions

The 2016 Top Islamic Financial Institutions ranking marks a return to growth, however. Total assets increased by 13.17% while the total profits of standalone banks increased to $13.68bn, up from $12.53bn in the 2015 edition. But the average return on assets for standalone institutions was 1.26% – the third lowest figure in the past decade. This suggests that although the industry is continuing its forward march, the tougher economic climate is beginning to take its toll.

“Next year will be another difficult one for the wider Islamic finance market. The biggest theme is the drop in oil price and the policy response it is triggering in core markets,” says S&P’s Mr Damak.

As growth in key markets begins to cool, most Islamic banks are likely to be hit with growing liquidity concerns as well as higher costs of risk (as are their conventional counterparts). Overcoming these problems, and others, will be a crucial test of the industry’s resilience.

But given their position of strength and the prudent business model typically adopted by sharia-compliant financial institutions, most Islamic banks will be able to take these hurdles in their stride. “To their credit, Islamic banks in the region enjoy good liquidity levels compared with international standards. Similarly, their capitalisation is strong relative to global norms,” says Mr Damak.

Nevertheless, cooling economic growth is not the only challenge facing the industry. As the Islamic finance market expands, the problems it faces are also growing. After a decade of breakneck growth, the sector as a whole is facing up to a new reality. Foremost in this is a need to spur further product and service innovation to better serve consumers.

While most Islamic financial institutions have been effective at replicating products and services from the conventional financial sphere, more work needs to be done to ensure that original offerings are generated and offered to customers. Institutions such as Malaysia’s International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance are working diligently to achieve this, but more investment is required by the private sector.

Innovation urged

“What is needed in the Islamic finance market is the creation of new products that do not have a similar counterpart in the conventional financial sphere. There is a real opportunity to innovate new products that are unique to Islamic finance,” says Joe DiVanna, managing director at Maris Strategies, a business think-tank and consultancy.

A notable and encouraging example is the Nasdaq Dubai murabaha platform. Launched in April 2014 after a short pilot, the initiative makes use of sharia-compliant certificates, based on wakala (contract of agency) investments that have been developed as the underlying asset for financing transactions.

Islamic financial institutions can then use these certificates to provide immediate cash financing to customers. Running on Nasdaq Dubai’s trading system, the platform allows institutions to make use of multiple asset classes for the underlying murabaha (mark-up or cost plus financing).

“Institutions need to focus on how they can fulfil the complex needs of consumers when it comes to sharia-compliant products. To do this, they need talent and resources at their disposal to research and invest in a wider set of offerings,” says the FAA’s Mr Amat.

But herein lies a further challenge. Innovation requires expertise, including dedicated and well-trained personnel to research new ideas, as well as the requisite professional class to oversee the commercial application and development of these concepts.

Need for new blood

Today, the Islamic finance sector is facing a dearth of qualified and skilled professionals who will be vital to its long-term growth. Concern among industry leaders is growing even as a number of public and private sector institutions are looking to bolster their training and accreditation capacity.

Malaysia’s FAA, for instance, offers a recognition of learning to long-serving professionals who may lack official qualifications, even as they have developed a sound working knowledge of the Islamic finance industry.

Mr Amat says: “Islamic financial institutions around the world are facing an acute shortage of specialised human capital. There is a mismatch between the supply and demand of Islamic finance professionals in the areas of risk management, compliance, auditing and sharia supervision. This is where accreditation and the quality assurance it brings can play a role in closing the gap.”

Developing a new generation of well-trained Islamic finance specialists may also help to address the fragmentation of the global market. Because although the industry has ballooned in recent years, its growth has largely emerged from dominant markets – including Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia – with little convergence between them. This has meant that professional, legal and sharia-compliant standards differ between jurisdictions.

Harmonising standards

Harmonising these standards will be vital if the Islamic finance marketplace is to achieve any measure of global unity. At present, basic transactions, including sukuk (Islamic bond) issuance, can be complex and time consuming due to a lack of standardised legal and sharia documentation. This is not helped by the fact that different markets may have different definitions of what is and is not sharia-compliant, meaning that sharia documentation cannot be easily applied across borders.

“When the oil price dropped many projected a windfall of sukuk issuance. But this did not materialise. Issuing sukuk remains complex and even if a government is a frequent issuer it can take time. So if a sovereign needs a sum of money quickly, it is unlikely to look to the sukuk market,” says Mr Damak.

The exception to this is Malaysia, which has developed an effective framework for sukuk issuance. But in 2015 the country's central bank, Bank Negara Malaysia, suspended its programme of short-term sukuk issuance, which has hit the total volume of transactions hard. S&P expects global issuance to reach between $50bn and $55bn in 2016, down from $63bn in 2015 and more than $100bn in 2014.

“The process of issuing a sukuk should be as straightforward as issuing a bond but we’re not there yet and this is why sukuk is experiencing a slowdown this year,” says Mr Damak.

The harmonisation of legal documentation and sharia-compliant standards are being tackled by, among other actors, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and the Accounting and Auditing Organisation of Islamic Financial Institutions.

The IDB, for instance, has a sharia board staffed by scholars from a number of jurisdictions and different schools of Islamic jurisprudence. Together, they are looking at ways to achieve a greater cross-border standardisation of sharia compliance.

Banking the unbanked

Addressing these challenges, and others, will take time. It will also take the collective efforts of public and private sector entities from across the Islamic world. But above all else, the industry’s future growth will depend on the ability of the Islamic finance market to penetrate underserved Muslim populations in high-growth markets such as Indonesia, Pakistan and Nigeria. According to The Banker’s latest research, about 75% of the world’s Muslim population is underbanked or lacks access to financial institutions.

This represents both a challenge and an opportunity for Islamic service providers moving forward. For one, it means that stellar growth potential still exists for Islamic financial institutions even as the global economic environment begins to cool. But reaching out to these new customers is likely to be difficult, and a process that will require further investment in technology and associated outreach initiatives.

“Islamic financial institutions will need to address issues around distribution and market outreach. This is particularly the case in relatively young but high-volume markets such as Nigeria and Pakistan, where banks need to improve their digital and alternative distribution channels to reach out to new customers,” says Maris Strategies’ Mr DiVanna.

Embracing technology

Islamic financial institutions have traditionally lagged in the development and application of digital banking technology. However, this situation is changing, with several banks now boasting world-class digital banking offerings, particularly in Malaysia and the GCC region.

Moreover, financial technology (fintech) is increasingly focused on sharia-compliant developments, with customer analytics and new investment platforms coming to the fore with greater frequency.

Exporting these ideas and concepts to higher growth markets will be one means of ensuring that underserved communities can gain access to Islamic financial services. This process could be accelerated by the role of regional banks, who could act as a bridge between developed and emerging centres of sharia-compliant finance.

“What is really needed is the emergence of a super regional bank that can facilitate cross-border transactions. This is happening in south-east Asia, with Malaysian banks acting as a bridge between Indonesia and their home markets. But it isn’t happening in the Middle East and Africa,” says Mr DiVanna.

As many industry players note, the role that Islamic finance can play in promoting financial inclusion falls squarely within agenda of many development initiatives. One of them, the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is seen by some as an opportunity for the industry to demonstrate its potential, as well as the positive contributions it can make to global development.

“When you look at the SDGs and Islamic finance, there is a natural connection between the two,” says Mr Damak.

Ethical take on finance

Many Islamic finance providers see their industry as a standard bearer of ethical finance. The move by many Islamic banks, for example, to rebrand the ‘Islamic’ component in their title is part of a wider initiative by thought leaders in the market to position sharia-compliant finance as an ethical and sustainable alternative to the booms, busts and uncertainty of its conventional counterpart.

As The Banker’s 2016 ranking makes clear, the Islamic finance industry is in good health. While its growth trajectory has moderated, it continues to outpace global norms. But this year’s rankings also underline the fact that, as a market, Islamic finance is now transitioning to the next stage of its development.

This will require institutions to become more efficient, by addressing the compliance costs associated with meeting sharia standards, and to look to technology and innovation to drive their future development.

“A good foundation has been established. It’s now time for the industry to enter a new phase of growth based on innovation and product development,” says Mr DiVanna.