A brave new world of mobile money

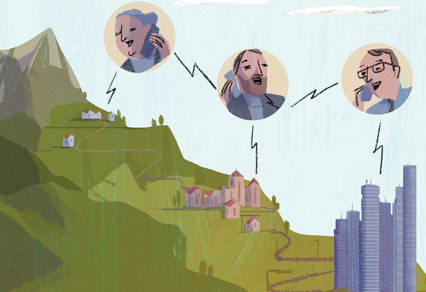

While mobile money usage has been gradually ramping up over the years, interoperability, alongside cheap and ubiquitous smartphones, has the potential to kick it up a gear. Joy Macknight reports.

Mobile money’s potential to bring into the folds of the formal financial system more than 2 billion unbanked individuals – 38% of the world’s adults – is phenomenal. Developing countries and emerging markets will derive a gamut of well-documented benefits from financial inclusion, from economic growth to social wellbeing.

According to the Groupe Spéciale Mobile Association’s (GSMA’s) 2015 state-of-the-industry report, mobile money is now available in 85% of countries where the vast majority of the population lacks access to a traditional financial institution. At least 19 markets have more mobile money accounts than bank accounts.

Double challenge

Importantly, regulators across the world have taken great strides towards creating an open and level playing field for mobile money service providers – 51 of 93 countries have an enabling regulatory framework, according to the GSMA. Previously considered to be the key obstacle to adoption, other barriers have now come to the fore, including two interconnected challenges: industry collaboration and interoperability; and developing compelling use and business cases.

“In markets where mobile money is not yet available, low investment due to the lack of a strong business case is one of the primary obstacles to launching new services,” says Jorn Lambert, executive vice-president, digital channels and regions, at MasterCard. “If the market size is small or the use case is not compelling for consumers, it’s harder for a mobile money service provider to achieve scale and profitability, making it less attractive to mobile operators and banks to invest in mobile money.

“Even where mobile money services are available, they often have limited utility due to a closed loop set up. To make these truly relevant to the consumers, we need to aim for global interoperability, and offer mobile payment services that permit multiple use cases, including in-store, peer-to-peer [P2P] and online payment.”

The power of collaboration

Interoperability is not only critical for building scale but also fostering competition, which makes mobile money solutions cheaper for the end consumer. Mr Lambert believes that the benefits of interoperability are becoming more evident. “There is a growing interest in leveraging interoperable solutions, which will strengthen the business case and improve the customer experience by making it easier for consumers and businesses to send money across networks,” he says.

Tanzania is a good example of the benefits interoperability can deliver. While most highlight the success of Kenya’s mobile money flagship, the M-Pesa model was built on the dominant market share of a single mobile operator, Safaricom. This monopoly provided grounds for Safaricom to make the investment necessary to build a mobile money brand and create an extensive cash in/out agent network, “giving it some certainty that it would recoup the investment”, according to Tilman Ehrbeck, a partner at Omidyar Network, a philanthropic investment firm established in 2004 by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Its southern neighbour took a different approach and fostered interoperability across the three biggest mobile network operators – Tigo, Airtel and Zantel – and is now adding more networks to the agreement. In just over a year, Tanzania is already overtaking Kenya in terms of usage and at a much lower cost. After putting these measures in place, Tanzania saw a 3.5 times increase in the value of off-network transactions, according to a recent report from Better Than Cash Alliance (BTCA) – a global partnership of businesses, governments, international organisations and philanthropic foundations promoting the use of digital payments – entitled ‘Accelerators to an inclusive digital payments ecosystem’.

“[Tanzania] is positive proof that interoperable rails will tremendously enhance the reach and adoption of mobile money,” says Kosta Peric, deputy director, level one digital payment systems, at the Financial Services for the Poor initiative of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Crossing borders

The mobile network operators (MNOs) are now collaborating on cross-border remittance corridors between Tanzania and Rwanda. “Interoperability at an international level could have huge implications for increasing efficiency in international trade,” says Camilo Tellez, head of research at BTCA. “The pot is getting bigger and players can take advantage of economies of scale in digital financial products across borders.”

Whereas the Tanzanian model is MNO-led, in Latin America Peru took a different path to interoperability. The Peruvian banking association (Asbanc) collaborated to create a shared infrastructure and then invited the MNOs to participate. Earlier in 2016 Pagos Digitales Peruanos, a company set up by Asbanc, went live with Bim, a mobile payments platform.

Francesco Burelli, managing director of payments strategy at consultancy Accenture Payment Services, believes Peru is a good example of “a whole ecosystem coming together for a specific purpose with a solution that looks well designed for the scope that it is intended for”.

He adds: “When the adoption increases and the use cases become more sophisticated, then ‘Modelo Peru’ will need to evolve its mobile money capabilities. But for the time being this solution is well designed to support not only financial inclusion but also the electronification of payments and savings, and potentially faster economic growth within segments of Peruvian society.”

A few pieces still have to fall in place, such as delivering financial education and extending the user cases beyond P2P, but Mr Burelli has little doubt that Peru, with the proper support and skills, will “become an interesting study for the evolution of this industry”.

Initiatives in Asia

Like Peru, Pakistan follows a bank-led model, but very early on the regulators allowed for collaboration between banks and MNOs. Three of the five telecom operators in the Pakistani market have acquired either majority or 100% shares in microfinance banks in order to have more control over mobile money products and services, the GSMA reports. For example, Tameer Microfinance Bank, in which Norway’s Telenor has a majority stake, is one of the country’s biggest mobile money providers. “Of the MNOs, Telenor is one of the most committed with operations in Pakistan, Bangladesh and more recently Myanmar,” says Mr Ehrbeck.

He believes that the old definition of a bank- or telco-led initiative is a little misleading because mixed forms have always existed, depending on the regulatory environment. “Telenor acquired a bank in Pakistan, while bKash in Bangladesh is majority-owned by Brac Bank, so it operates under a banking licence but with an independent telco mindset,” he says.

Myanmar is a unique case. When the country began opening up in 2013, its regulators took a decision to include mobile money in the country’s mobile telephony licensing process. It required international providers, Telenor and Qatar-based Ooredoo, as well as the incumbent Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications, to launch mobile money offerings within a year of operation. The country leapfrogged into the 3G world, importing cheap smartphones from China and receiving good advice from the international development community about best practices in mobile money.

Mr Ehrbeck says: “Myanmar is the first and only country where mobile telephony and mobile money are being introduced almost at the same time. Mobile money regulation passed in April this year and by all accounts service is being taken up rapidly.”

All eyes on India

Many believe, however, that India may be the next frontier in mobile money. While initially the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country's central bank, had concerns about letting MNOs become e-money issuers, under previous RBI governor, Raghuram Rajan, it decided to redefine what constitutes a bank. In August 2015, it introduced a payment bank licence, which opens the door for MNOs to become regulated financial services providers.

In addition to the new licences, the Indian government is creating a new digital infrastructure, called 'India Stack', which is a complete set of application programming interfaces and builds on the unique biometric identity system Aadhaar.

To date approximately 1 billion people are registered with Aadhaar using an iris scan. The regulators, including RBI and Securities and Exchange Board of India, allow the Aadhaar identity system to be used for authentication.

India is now working on a digital signature layer. In addition, the National Payments Corporation of India launched a uniform payment interface, which allows any account-to-account transactions at a low cost.

"India is pulling together a digital infrastructure – e-know your customer, e-signature, payment interface – that will dramatically accelerate the development of highly appropriate, tailored and far lower cost financial services,” says Mr Ehrbeck.

Finding the killer apps

Despite these important advances – and a 31% global increase in registered mobile money accounts, according to GSMA – many markets are still struggling to move mobile money beyond P2P payments and remittances. Identifying use cases that address real consumer needs must now be a priority, according to Greta Bull, CEO of Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), a global partnership of 34 organisations that seek to advance financial inclusion.

“The industry is asking people to move from something they are comfortable using – cash – to something that is far less intuitive and can come across as intimidating to those not accustomed to using bank accounts or technology,” she says. “It is important to understand what low-income and mass-market consumers want, and how they interact with technology should be a priority for all mobile money providers.” She believes that design features need to be improved so that they are more intuitive, user friendly and transparent.

“The big question is how to convince people, who are used to using cash for their daily and monthly transactions, or have informal loans or savings, to trust that a mobile initiative will be substantially more efficient, cheaper, accessible and safer,” says Fernando de Olloqui, a financial markets lead specialist Inter-American Development Bank. “However, if you give them a value proposal, then they will switch.” He gives the example of a small shopkeeper paying an electricity bill electronically, instead of closing the shop for two hours to pay the bill in person.

Mr Burelli stresses the need for education to change consumer behaviour to the point where mobile money is seen as a viable alternative to cash and an opportunity to store money electronically, instead of just being a channel for remittance or basic payments. “Mobile money is a great tool but from there to a cashless society is a long way,” he says.

New business models

Looking at it from the business case perspective, Mr Tellez argues that countries should shift to developing a regulatory framework for second-generation services that encourages innovation but also protects consumers. “We are starting to see some markets move from the initial use case, which was basically P2P domestic remittances, towards a new generation of products, such as insurance, savings and credit, as well as some fintechs that are starting to plug into mobile money platforms.”

While third parties, whether start-ups or arms of the MNOs or banks, are starting to take advantage of the data emerging out of platforms, unbundling services and creating new products, Mr Tellez believes that the regulatory frameworks are not developed enough to allow for a fully flourishing ecosystem.

In spite of these impediments, mobile money is clearly fostering new business models. Omidyar Network’s Mr Ehrbeck provides two examples. The first is using data for underwriting loans. “There are probably 1 billion people in emerging markets who don’t have a credit score because they don’t have regular employment, etc. But they do have a digital footprint, for example cell phone usage, mobile money or payments history, and if they have smartphone, then they have a search history,” he says.

“This information, if available, has power from a credit underwriting perspective. For example, the number of unique incoming calls can be used as an indication of the individual’s social network strength, which is an indicator of creditworthiness.”

Omidyar Network has invested in companies such as Lenddo, which started with social media data; others generate data and, for example, use psychometric testing in a small business lending context. The firm published a report, ‘Big data, small credit’, earlier in 2016, which takes an in-depth look at technology companies that are disrupting the credit scoring business in emerging markets.

Savings and investment is the second area where Mr Ehrbeck believes digital connectivity and mobile money are enabling new business models. Omidyar Network has also invested in Scripbox, one of India’s fastest growing investment services. “Almost 70% of its clients are first-time investors, the aspiring Indian middle class,” says Mr Ehrbeck.

Encouraging innovation

Both examples illustrate how the intersection between mobile money and new entrants, such as fintech start-ups, is creating a new space for innovation. “Fintech is influencing mobile money by realising what could be done with the available transactional data,” says Harish Natarajan, senior payment systems specialist, finance and markets, at the World Bank. “This opens up potentially new revenue streams and that in itself becomes a reason to be in this space.”

In addition, new payments players are finding ways to provide remittances services at much lower cost than traditional providers. “There are many different ways that fintech providers are engaging in the mobile money space, and they are making it a much richer ecosystem,” adds Ms Bull.

Mobile money is also encouraging new partnerships between traditional financial institutions and fintechs. For example, Finca, a microfinance institution, recently partnered with a Pakistan-based fintech called Finja to increase financial inclusion in the country through a ‘fully strapped’ mobile wallet with savings and other services beyond payments such as loans. “Customers can do all their bank transactions remotely, even account opening,” says Rupert Scofield, the co-CEO at Finca.

Finca has signed up 5000 retailers in Pakistan who are willing to accept payments via the mobile wallet. It has completed the first pilot with 1200 employees and plans to roll out the product to the first 5000 customers in October.

Smartphone ubiquity

All indications suggest that the competitive landscape in mobile money is facing another seismic change as the mass migration to smartphones – and the global move to 3G and beyond – continues.

“With smartphone access to broadband and Wi-Fi, a new set of players can enter the market, for example Alibaba and Alipay – they will change the dynamics,” says Sacha Polverini, chairman of the UN's International Telecommunication Union focus group on digital financial services.

BTCA’s Mr Tellez highlights a shift in mobile money with the emergence of payments over social messaging platforms, such as WeChat which has 600 million customers. “People can perform myriad transactions on these platforms, from purchasing insurance to ordering food, shopping online, sending money to friends or buying stocks – all through one app without leaving the platform.”

Additionally, Mr Polverini expects the overall user experience to improve on a smartphone, which may solve the interface design issues raised by CGAP’s Ms Bull. “There are more graphics and it is more intuitive than the current menu. The interface and speed of the transaction will be totally different,” he says.

Ms Bull agrees. “Not only do smartphones bypass challenges with the unstructured supplementary service data channel normally used by mobile money providers, but they are also more intuitive for customers and offer a platform where innovators can build apps that meet the needs of the markets they are trying to serve.

“There is so much interesting innovation going on, it is an exciting time to be in the mobile financial services space.”