Are commodity currencies coming off the boil?

Commodity currencies have posted record gains in the past two years, fuelled by spiralling demand for food and materials. But some of these countries are now struggling to offset runaway inflation, and the rate of inflows is such that central banks are becoming increasingly helpless to reverse the pressure on their currency.

As global living standards continue to rise, demand for food, energy and metals is increasing exponentially. In July, food prices hit the highest levels ever recorded, while in May, oil prices rose to $125 a barrel, the most expensive since 2008. In August, gold topped $1900 an ounce, as investors sought safe havens from depressed equity markets.

In a circular case of cause and effect, higher commodity prices have boosted inflation in commodity-producing countries, leading to hikes in interest rates, which in turn have attracted waves of global capital seeking carry-trade returns.

Editor's choice

Lack of alternatives

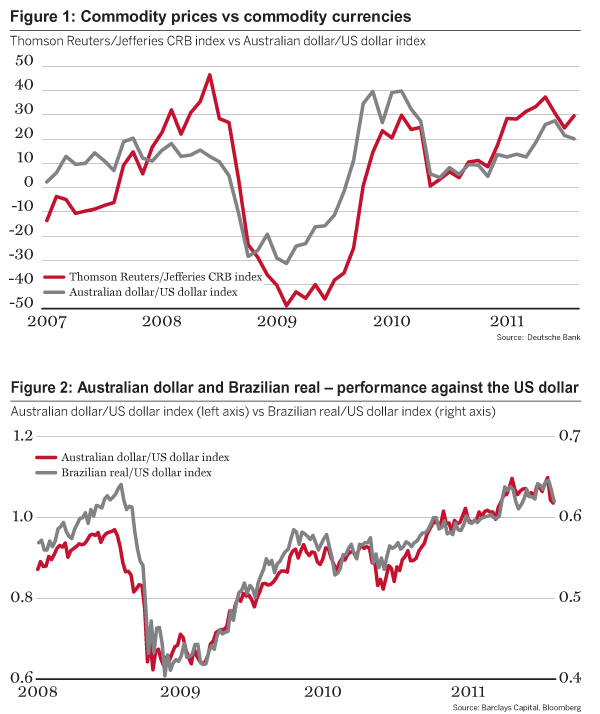

In the past two and a half years, the Australian and Canadian dollars and Norwegian krone have risen against the US dollar by 60.4%, 25% and 26.5%, respectively, according to JPMorgan Private Bank. Figure 1 illustrates the strong correlation between commodity prices (Thomson Reuters/Jefferies CRB index) and commodity currencies (represented by the Australian dollar).

The downgrade of the US sovereign rating to AA+ by rating agency Standard & Poor’s in early August could mark a turning point, analysts say. Slower growth or recession in the world’s largest economy will dampen demand for commodities in the medium term. Concern over the fate of the US economy, and that of some countries in Europe, will attract capital flows to less risky assets.

“Commodity currencies have lost some of their appeal,” says Audrey Childe-Freeman, head of currency strategy in Europe, the Middle East and Africa at JPMorgan. “They have come down from the really convincing upward trend seen since the beginning of the year, although the longer-term outlook remains supportive.” Despite weakening investor confidence, commodity currencies have remained resilient in recent weeks, perhaps a reflection of the lack of alternatives.

Diminishing US dollar

According to Robert Hyman, manager of the commodity strategy allocation fund at Jefferies Asset Management, there is a “tendency [for] commodity-rich... countries to rebound from financial difficulties more quickly and to prosper as the world recovers”.

As a result, currencies such as the Australian dollar, Brazilian real and Norwegian krone may be regarded as a better store of value than the US dollar, the euro or UK sterling, suggests Michael Derks, chief strategist at foreign exchange brokerage FX Pro. “The extent to which commodity currencies have performed strongly reflects, to some degree, scepticism about the solidity of some of the major currencies,” he says.

The extent to which commodity currencies have performed strongly reflects, to some degree, scepticism about the solidity of some of the major currencies

Mr Derks’ comments hint at a broader change in the currency markets that favours smaller currencies. Over the past 10 years, the role of the US dollar as a reserve currency has diminished considerably, with currency reserves denominated in dollars down from more than 70% in 2001 to close to 60% at the beginning of 2011, according to figures form the International Monetary Fund.

Resilient prices

As well as holding up strongly in the foreign exchange markets, commodity currencies have also benefited from the relative resilience of commodity prices themselves. “Although commodity prices have felt the impact of the recent re-evaluating of global growth expectations, they have fallen by less than other risky assets, such as credit and particularly equities,” says Guillermo Felices, European head of FX research at Barclays Capital.

Research by Barclays Capital demonstrates that the correlation between commodity currencies has become more acute in recent years, and particularly at times when investors are more risk averse. “Since the onset of the global financial crisis, commodity currencies have behaved very similarly across the board,” says Mr Felices.

Domestic differences

This is surprising considering the differences in domestic circumstances. Brazil, for example, is a low-income emerging economy that tends to fight appreciation pressures, while Australia has the opposite characteristics. Yet their currencies’ performance against the US dollar is almost identical (see figure 2).

An exception to the rule is the Canadian dollar, which has trailed its Australian peer, with the latter benefiting not only from rising commodity prices but also from its position as a key trading partner with the Asia-Pacific region. “The investor can choose between Australia, offering a yield of 4.75% and giving exposure to the China growth story, versus Canada with a yield of less than 1% and exposure to an uncertain outlook for the US economy,” says JPMorgan’s Ms Childe-Freeman.

Domestic circumstances can also affect a country’s ability to cope with the strength of its currency. For some, rising currency values on the back of rampant commodity demand have been welcome.

In Australia, for example, the strong currency has helped to provide a good counterweight to domestically driven inflation-related pressures. The country has been able to absorb a rise in its currency owing to a strong domestic economy and, in particular, a tight housing market. The Reserve Bank of Australia has addressed this by raising interest rates over the past two years to 4.75%, a level that has remained stable so far this year. However, with inflation creeping up to 3.6% in the second quarter of 2011 from 3.1% a year earlier, interest rates may need to rise further, threatening to stymie economic growth.

The investor can choose between Australia, offering a yield of 4.75% and giving exposure to the China growth story, versus Canada with a yield of less than 1% and exposure to an uncertain outlook for the US economy

Brazil, on the other hand, has a much lower tolerance of currency strength. As with fellow commodity producer Chile, Brazil’s government has repeatedly intervened in a bid to tame its robust currency. But it continues to struggle in the face of the weak US dollar and high interest rate differentials with the US, which attract capital inflows.

Brazil’s monetary authorities raised the country’s reference Selic interest rate by 1.75 percentage points this year to a towering 12.5%, before pulling back to 12% in August. The moves have not been sufficient to stem inflation, which rose close to 7% in July, up from 4.6% a year earlier.

Intervention policies

The Banco Central do Brasil and other government agencies have also put in place new and higher taxes on capital inflows, such as a 1% tax on short dollar positions, but doubts remain over the policy’s impact. “Even if Brazil were to tax inflows further, with interest rates of 12%, there is still decent carry, with rates in major economies close to zero,” says Henrik Gullberg, FX strategist at Deutsche Bank.

Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, has also intervened to try to stem rises in its currency. With the peso trading at near three-year highs against the dollar, its central bank initiated a $12bn currency intervention programme at the beginning of this year, and has purchased $8.25bn so far. Chile has also raised interest rates five times this year, with the benchmark rate currently at 5.25%.

Results have been inconclusive. “Intervention can have a short-term impact. It can limit the speed of appreciation, but rarely will it change the direction in which fundamentals are pointing,” says Mr Felices. “It has been really difficult for the central banks of Brazil and Chile to engineer a sustained depreciation of the real or the peso because fundamentals have been going the opposite way.”

Overheating currencies

The sheer volume of global foreign currency flows militates against attempts to control exchange rates. “The global markets are so big that it’s very difficult for one central bank to reverse the pressure on its currency,” says Mr Gullberg. “It’s a common theme that when authorities have taken measures to drive down their currency – whether it is commodity producers or countries such as Switzerland and Japan – they have not been successful,” he adds.

Figure 2 offers a clear illustration of how limited the impact of Brazil’s currency intervention has been, with the real continuing to rise unabated. “Brazil is in a vicious circle,” says Mr Gullberg. “As interest rates have gone up, this has attracted more capital inflows in the form of carry trades, generating yet more currency appreciation.”

Carry trades involve selling a low interest rate currency such as the US dollar and using the revenues to buy a currency that offers higher rates. They have attracted enormous speculative capital inflows into the higher yielding commodity currencies, particularly the Brazilian real and Australian dollar.

In June, foreign net dollar shorts (that is, the value of bets that the US dollar will weaken against the real, minus the value of bets that the dollar will gain against the Brazilian currency) reached more than $20bn[1]. This speculative investment by global currency traders has exacerbated the problems felt by countries with overheating currencies.

“Genuine capital inflows are generally helpful to the economy. But portfolio flows, where traders invest in a currency because they think it is going to appreciate and want to take advantage of higher interest rates, are much less helpful,” says Mr Derks at FX Pro. “They are a type of capital inflow that most countries would prefer to avoid.”

According to Mr Gullberg, the volume of carry trades has tailed off sharply since the beginning of August, in line with growing risk aversion. Higher volatility in this period has also helped to make the carry trade less attractive, particularly in the Australian dollar.

“In the past four months, the Aussie dollar has traded in a narrow band between 105 and 110 against the US dollar. In the first few days of August it fell by 10% to below parity before recovering back,” says Mr Derks.

[1] Source: Calculated by Reuters based on data from São Paulo’s BM&F commodities and futures exchange