Asia fails to balance currency and inflationary pressures

Asian policy-makers have been trying to balance currency management with controlling inflation. Raising rates brings capital in and pushes currencies up. Keep them too low and inflation spirals out of control. Put rates up too far or too fast and capital leaves. Rising inflation and rising currencies suggest policy makers have failed to get the balance right.

In Asian currencies, the trend seems to be ever upwards. Last year the continent's currencies saw their biggest gains since 2006. The Bloomberg-JPMorgan Asia Dollar Index, which tracks the 10 most actively traded Asian currencies excluding the yen, climbed 5.2% in 2010 on the back of strong economic growth and rising interest rates.

Editor's choice

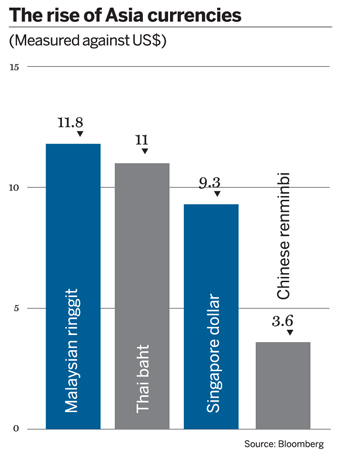

Notably, the Chinese renminbi rose above 6.6 per dollar for the first time in 17 years, bringing the currency's gains to 3.6% in 2010. But, while the world may be focused on the rise of the renminbi and the battle between it and the dollar, it is not the only Asian currency with strong fundamentals. Malaysia's ringgit appreciated the most in Asia last year, rising by 11.8%, followed closely by the Thai baht, which rose by 11%, and the Singapore dollar, which climbed by 9.3%.

Towards the end of January and the beginning of February, most emerging Asia currency appreciation stalled, amid falling risk appetite in the face of rolling social and political unrest in north Africa and the Middle East. But strong growth and rising interest rates since then (Indonesia, China and South Korea all raised rates in the first quarter of 2011) have attracted foreign capital and only increased the upward pressure on the region's currencies.

Emerging growth

The International Monetary Fund says that Asia's emerging economies will have expanded by 9.4% in 2010 versus 2.7% in developed markets, pulling significant capital flows into Asian economies. In 2010, $63.4bn of foreign capital flowed into stocks in India, Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand. This follows the trend across all emerging markets. According to fund tracker EPFR Global, almost $150bn went into emerging market bond and equity funds in 2010.

The impact of these capital flows has caused several Asian governments to put up barriers to curb inflows of foreign funds. With central banks already grappling with consumer price pressures fuelled by employment and spending gains, continued inflationary pressures (pushed even steeper by a hike of more than 20% in crude oil costs in just two weeks to March 8) have led to limits on foreign holdings of local currency investments and attempts to channel inflows away from short-term investments.

Ominous warning

In a report released in the second week of March, ratings agency Standard & Poor's stated such levels of inflation (which it says pose a risk to economic and social stability in Indonesia, India and other countries) highlight the difficulties of dealing with capital flows. The agency said dealing with inflation could complicate currency rate management, or lead to “overkill” when trying to tackle capital in-flows; the report cited countries including Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand.

The report also warned that the difficulty of managing these tricky and often countervailing trends means that the threat of trade wars has not disappeared.

"As a general principle, capital controls and other measures to keep a currency's value artificially low are a double-edged sword, as they can result in retaliatory actions in the form of trade tariffs or quantitative restrictions," the report said. “China is getting embroiled in such a tussle, and the implications for the rest of Asia have been a major worry for some time.” It added that the persistence of high US unemployment and approaching mid-term elections raise the risk of US retaliation.

However, the report also noted that China's recent steps to allow the yuan to gradually appreciate could reduce the possibility of trade tension. Moreover, Standard & Poor's, which expects Beijing to take more policy steps to stabilise inflation, suggests that the country's policy-makers may allow the renminbi to appreciate “significantly more than in 2010” if export levels remain healthy.

Inflation worries

But with inflation still an issue – Vietnam's consumer price index rose by 12.3% in the 12 months to February 2011 – the threat of even sharper rate hikes combined with jittery risk appetite to suck foreign capital out of Asia. Year-to-date, about $1.6bn has been withdrawn from the Indian equity market and about $2bn from the South Korean market. Bankers also report money flowing out of bond markets, increasing financing costs and making it more difficult for domestic companies to raise capital. At the same time, inflation is still rising.

Controlling currencies and fighting inflation requires an almost impossible balancing act. With currencies still trending upwards and inflation still rising, it looks as if policy-makers have yet to get it right.