Central banks focus on reserves and currencies

John Normand, global head of foreign exchange strategy at JPMorgan

Central banks have dropped their traditional low profile - becoming more proactive, accumulating large reserves and intervening actively to support their national currencies and interests. The composition of their reserves is also changing, with a number of central banks considering moves to reduce their exposure to the US dollar, reports Joanne Hart.

Central banks used to be the shy cousins of their commercial counterparts. Rarely seen, they were shadowy figures in the hinterland of the global financial landscape, emerging only to conduct occasional spot intervention or deliver Delphic pronouncements about economics and currency flows.

The US Federal Reserve was an exception to the rule, but these days a growing number of central banks are becoming more vociferous, more high profile and more influential.

According to some estimates, more than $15,000bn is now being managed by central banks and their offshoots, sovereign wealth funds. China alone has reserves of about $2500bn, Japan has more than $1000bn and other central banks, including those of Brazil, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia and South Korea, have several hundred billion dollars each of reserves in gold and foreign currency. "Over the past couple of years, the number of central banks accumulating reserves has increased. Many have reserves of at least $20bn - that is as much as some of the largest hedge funds," says John Normand, global head of foreign exchange strategy at JPMorgan.

Response to crisis

The change has largely come about in response to the 2008 financial crisis but, for Asian banks in particular, the seeds were sown a decade earlier, during the region's own period of financial meltdown.

"Back in 1998, South Korea thought it had plenty of reserves, but it did not have enough to protect itself at that time. The crisis caused a number of Asian central banks to believe that they needed a bigger armoury to control or influence their currency. They were very keen to make sure they had enough foreign exchange [FX] reserves, so they built them up dramatically and have continued to do so ever since," says Kit Juckes, global head of FX strategy at Société Générale Corporate & Investment Bank.

This strategy has intensified since the collapse of Lehman Brothers and its aftershocks spread to other parts of the world. Central banks across the globe have concluded that financial markets can be volatile, dangerous and unpredictable. Some banks thrive on this type of environment but central banks are different.

"Central banks can be accused of holding unusually high reserve levels, but what might seem excessive in good times can be depleted quickly in a crisis. It is not useful to judge a central bank's reserves as excessive, since these institutions may have other objectives. A number of central banks operate in export-led economies that want to keep their currencies cheap. Accumulating foreign reserves is the easiest way to do this," says Mr Normand.

The strategy is well known. Export-led economies sell goods to hungry, consumerist nations; they amass wealth but they do not want their domestic currency to strengthen, because this will reduce their competitive edge. So they buy as much foreign currency as they can, thereby reducing the relative value of their own coinage. The classic example of the past decade has been China - and the currency it has chosen to invest in most heavily has been the dollar.

Currency manipulation

China may be the country most frequently accused of 'currency manipulation', but it is not alone. And, while certain policy-makers in the US and Europe rail against the Chinese for artificially depreciating their currency, China is not totally to blame for the status quo.

"The US, Europe and Japan are weighed down by massive amounts of debt, so everyone else is trying to prevent their currencies appreciating against this collective, bloated credit albatross," says Mr Juckes. "Countries [that have accumulated] monstrous debt levels from partying too hard over the past decade and more are the losers, but the rest of the world is trying to live with being the winners." It may sound counterintuitive that it is tough to be the winner, but it is harder than it seems.

"Central banks have limited options because their mandates, while expanding, are invariably very restrictive," says George Magnus, senior economic adviser at UBS.

Liquidity constraints

Liquidity is crucial for central banks, and this means further constraints on strategy. "Most central banks tend to hold reserves in relatively short-dated, relatively vanilla instruments. They need to retain liquidity so that they can intervene in the markets at short notice if need be," says James Davison, the head of FX structuring for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at BNP Paribas.

Moreover, the sums at stake are often so large that only a few markets are capacious enough to take them. "They [central banks] need deep, liquid markets; the US capital markets are the broadest and deepest, so they are forced to invest in US treasuries - even though interest rates are low and there are grave doubts about the US economy," says Mr Magnus.

And this means that the currency composition of central banks' reserves is misaligned, says Mr Normand. "It is a legacy from the era when most countries pegged their currency and the dollar was the most liquid reserve asset," he says.

Broadened investment remit

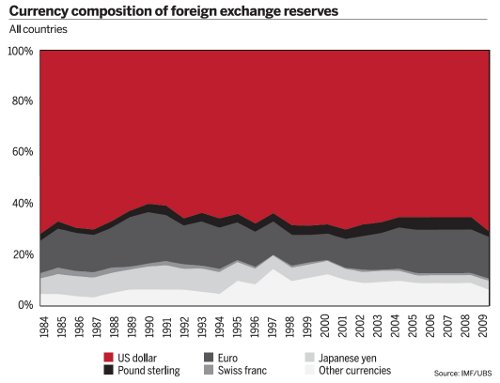

In recent years, central banks have broadened their investment remit slightly. The creation of the euro, for example, produced a currency with a depth and liquidity to rival the dollar and about 26% of reserves are now held in euros. Central bankers have also dabbled in areas such as mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities as well as sovereign bonds.

"There has been an ongoing move to diversify out of treasuries and into high-grade alternatives," says Mr Normand.

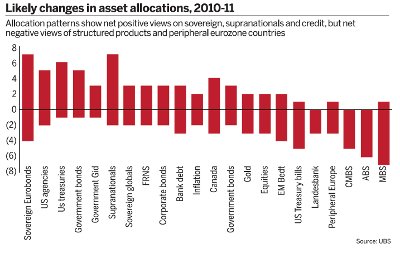

Some of these moves have been more successful than others. Most central banks are now keen to de-emphasise asset-backed and mortgage securities, as well as Landesbank debt and bonds from peripheral European nations. Indeed, the European Central Bank has spent some €60bn mopping up the excess supply of paper from less popular eurozone countries such as Portugal, Ireland, Spain and, of course, Greece.

Sovereign bonds from AAA rated nations are more in favour, as are supranationals, floating rate notes, bank debt and gold, according to a survey of central banks by UBS. Other firms suggest that there is also some interest from central banks in structured products, such as dual-currency deposits, where a bank deposits cash in one currency and receives an enhanced yield in return for giving the deposit-holder (the central bank) the option to redeem the cash in another currency.

"The crisis has pushed some central banks towards greater risk avoidance, while others have tended towards greater risk awareness. They have been investing more in risk management, looking more closely at risks versus returns and diversifying into other asset classes or markets," says Mr Davison.

Some have been doing this via sovereign wealth funds, which have a broader investment remit than central banks themselves, but results have been mixed. Billions of dollars were squandered on ill-fated rescue attempts of US banks, for example, although other investments in commodity or retail assets have been more fruitful.

Top dollar

Nonetheless, the dollar and dollar-denominated liquid assets still account for the majority of central bank reserves. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), central banks have invested about 60% of their reserves in dollars for the past 25 years, with remarkable consistency.

While the breadth of the US market makes this understandable, it has prompted increased unease among economists, foreign exchange strategists and central bankers themselves. "China is dissatisfied with a system in which it feels forced to invest in dollars and dollar-denominated instruments," says Mr Magnus.

Other emerging economies feel the same. Russia has been gradually reducing its exposure to dollars and many central banks with large reserves would prefer to be exposed to the currencies of countries in whose prospects they have more confidence.

But change has to be handled with great delicacy if it is not to have unintended consequences. The Swiss National Bank's attempt to weaken its currency by intervening in the foreign exchange markets earlier this year backfired spectacularly, leaving the country with euros it did not want and a stronger Swiss franc than ever.

"The Swiss franc has a safety element to it, so attempts to keep it low have simply not worked. The Swiss National Bank faces considerable losses as a result of intervention but, against that, it does not seem to have affected the [country's] economy, which is growing by 3.4% year on year," says Neil Mackinnon, global macro strategist at VTB Capital.

George Magnus, senior economic adviser at UBS

Moving into new areas

Moving into other currencies or asset classes is even more of a challenge for giants such as the Chinese.

"It might be a good idea for the Chinese to move into gold as part of a diversification programme but the mere speculation that they might increase their allocation would push up the price to such an extent as to make the investment a lot more questionable," says Mr Magnus.

Some central banks have deliberately gone for a high-profile approach, sending out signals to policy-makers and markets. The quantitative easing programmes undertaken by the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England are explicitly designed to ease volatility, although they are frowned on by many other central banks.

"Emerging economies do not approve of quantitative easing as they say it is debasing their assets. Some even threaten to initiate a buyers' strike. The debate is quite polite but there will be more and more dissatisfaction, particularly if the US economy does not start to recover," says Mr Juckes.

As the year draws to a close, some foreign exchange watchers believe further central bank movements may arise in light of changes to special drawing rights (SDRs). These were created by the International Monetary Fund in 1969 as an international reserve asset whose value is based on a basket of four currencies, currently the dollar, the euro, the yen and sterling. The basket is reassessed every five years and is due for a fresh reality check at the end of this year. While SDRs cannot be traded freely, the weighting is significant because it influences the way central banks allocate their reserves.

"At the moment, SDRs consist of 44% dollars, 34% euros, 11% yen and 11% sterling. Although no announcements have been made, it would not be a surprise to us if the basket were expanded to include commodity currencies such as the Canadian and Australian dollars. This could have a profound effect on markets and the way that central banks manage reserves," says Sunil Kapadia from the macro research group at UBS.

The role of a central banker is arguably harder than it has ever been. Perhaps the only compensation is that most think about currency management in rather different terms from their commercial peers.

"They have a 10- to 20-year timeframe, so they will reduce their dollar exposure gradually as the private sector demand for dollars grows," says Mr Normand.