Regulators are beginning to take an interest in the number of cases in which stock lending is being inappropriately used to influence voting. But no-one wants regulatory involvement and education could be the key, Dan Barnes reports.

The misuse of stock lending has brought the threat of the involvement of regulators – something that few in the business would want to see. An investigation into improving corporate governance practice for voting on stock has highlighted serious questions about the misuse of stock lending and borrowing by fund managers and corporations. Where it is traditionally used to allow traders and asset managers to run short positions, the current system is at risk of abuse when securities are borrowed or lent to influence voting and control of a company. Although the practice is not deemed illegal in most markets, it is not considered to be in the spirit of the law and recent incidents have brought the practice to regulators’ attention.

The limited voting of shares by institutions in the UK became an issue for the government when the Directors’ Remuneration Report Regulations 2002 amended the law to require remuneration to be voted on by shareholders. Finding that votes were not being used, Paul Myners, chairman of retailer Marks & Spencer and of the Shareholder Voting Working Group, looked into the issue and published a report detailing recommendations on how to improve the situation.

“As we looked at institutional voting, the increased consequences of stock lending became an area which needed attention and comment,” says Mr Myners. “When stock is lent, technically it is not a loan, technically it is a sale and repurchase and the vote goes as well.”

A vote for education

Institutional shareholders’ lack of understanding of the system created a need for reform in the area. Mr Myners believes that the ‘beneficial owners’ – those whose stock has been lent by a custodian – need to be educated about their voting rights, their ability to recall stock for voting and to ensure that the use of the votes is not abused.

The issue is international. Although Mr Myners’ work was focused on the UK, he says: “Similar issues do arise in some other jurisdictions… The work we have done has been picked up by others elsewhere, including the International Corporate Governance Network, which is very active now in the work it is doing on voting and stock lending.”

The lack of real understanding about voting, lack of concern and even apathy all contribute to the lack of votes normally cast but these can create a situation in which abuse of the system is easier to carry out, he says.

Abuse is difficult to measure and confirm. The purpose for which a stock has been borrowed or lent cannot easily be determined. Chris Taylor, senior vice-president at State Street Securities Finance, says that the economics are transparent but motivation is not. “As a rule, most lending occurs around the international markets dividend period and the voting is closely correlated with that dividend period, so decoupling that is important,“ he says.

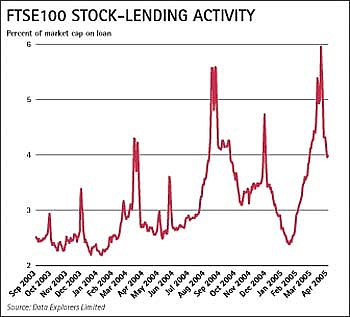

But correlation does not necessarily imply anything negative and there is the risk of misinterpretation when the data is examined. Wayne Burlingham, head of securities lending, institutional fund services, Europe at HSBC, notes that with the bank’s own stock there are lending peaks around dividend periods of anything up to 15%. But he adds: “In the UK as a whole, factual evidence shows that total lending activity only accounts for around 3%-4% of the total market capital of all stocks.”

Unclear picture

Although a borrower or lender will track its own dealings, the global economic picture for lending is fairly unclear. Data Explorers has been gathering information on the area since 2002 but still cannot put a fixed value on the market. Mark Faulkner, managing director at consultancy Spitalfields Advisors, believes that the value of securities on loan is at about $3000bn with a good possibility that the real figure is closer to $3500bn-$4000bn, with no signs of growth abating, partly driven by the rise of demand from hedge funds.

“In the first instances, many of the proprietary traders were working for the globally-renowned investment banks. In recent years, these banks have been, for want of a better word, outsourcing their proprietary trading to hedge funds. One weapon in their armoury is to trade short and that requires securities lending,” says Mr Faulkner.

Mr Taylor also observes that the growth in prime brokerage and hedge funds is fuelling demand for borrowing securities.

For a business such as custody where margins are under increasing pressure, lending provides a valuable income stream. And, because market circumstances are tougher for their clients, the incremental returns available from lending are of increasing interest to funds when looking at their relative success compared to their peers. Many custodians protest that the risks of abuse are small, often citing that only 3%-5% of stock is on loan from shareholders in the FTSE100 at any one time.

Bigger fish

The amount of stock being voted on is low, too, something that Mr Burlingham points out. “The average that is voted on is often at about 45%-50%, which sometimes means the majority of the shares are not voted on. The majority could obviously sway the vote in any direction. If we look at the loan market where our 3%-4% of stock is typically on loan, it is apparent that there are bigger fish to fry than stock lending if we are to resolve the issue of voting, but we suffer from being visible,” he says.

In fact, because the number of votes cast is so low – perhaps only 50% of the total – the impact of “borrowed” votes could be doubled. In other words, during peak periods – at dividend and voting times – up to 15% of shares can be borrowed. If shares are borrowed to influence voting, 15% possesses the potential voting power of 30% of stock. In the case of HSBC, for example, it peaks to 14%-15% on average, thus decreasing the stock needed to swing a vote.

Borrowing/lending has had an influence on voting and decision-making in a number of instances. Mr Myners notes the case of Laxey Partners and British Land as the one UK example. In 2002, Laxey Partners, shareholders in British Land, put forward a series of resolutions with a view to shaking up the property giant at the annual general meeting (AGM). Although the hedge fund was a shareholder in its own right, one week before the AGM it had borrowed 8% stock in the company to add to its initial 1%, temporarily giving it greater weight. The resolutions it put forward were defeated but nevertheless this highlights the influence that borrowed stock could have in board meetings.

More recently in Japan, Nippon Broadcasting System (NBS) lent a 13.88% stake (equalling 14.67% of voting rights) in its affiliate Fuji Television Network to Softbank Investment for a period of five years. The move followed the attempted issuance of NBS stock to Fuji TV, blocked by a high court judge, which would have lowered the stake of Livedoor, an internet portal that now owns more than 50% of NBS, to less than 20%. The lending deal prevented Livedoor from gaining a stronger hold on, or even taking over, Fuji TV using its position of strength in NBS.

The minister for financial services looked at the case and noted that, although stock lending is legal, measures will be taken if there is a lack of fairness in the marketplace.

Acquisition case

Mr Myners also highlights a case in the US in which lending was used to gain voting rights to increase financial return on owned stock. “Hedge funds were big investors in [company A] that was being bid for and there was a concern that the offer by the bidder, [company B], was too generous. So the hedge funds borrowed stock in [company B] in order to vote through the acquisition of [company A], in which they had a real economic interest.”

Mr Taylor argues that the 20-40 cases relating to concern over stock lending and voting rights in the past 10 years is nothing to worry about. “There aren’t many [incidents] and the vast majority of the stock is not voted, independent of any lending arrangement. If in any doubt, then recall your shares,“ he advises.

However, for beneficial owners who find their voting rights diminished or the boards that find stock borrowers swinging an important decision, these few instances are too many.

That said, no party would welcome regulation of securities lending. Mr Myners is clear that he would not be in favour. “I’m a free marketeer but I do think that a market requires a sensible regulatory framework. It requires people to be alert about what is in their best interests. This is not an area where regulation strikes me as likely to be the best solution.”

In some cases, this could be damaging to those in the business especially if, as typically happens, implementing a solution incurred greater costs. There is the potential to drive smaller custodians into difficult positions or out of the market entirely, according to Ian Hovey, treasurer of the International Securities Lending Association.

“If regulation were to be detailed or more specific, there could be a highly associated cost with change, particularly around systems and reporting aspects. The cost of changing systems is quite significant and a small player may well be faced with a position where they think it’s now an uneconomic activity to conduct,“ says Mr Hovey.

Mr Myners believes that the only real option is for greater awareness on the part of beneficial owners. “The only solutions are to ban stock lending altogether – which would be very harmful in terms of liquidity – or say to the people who own shares ‘be careful, be alert’.”

Straightforward options

Better management by stock owners appears to be the preferred route to ensuring that the system is not abused. Recalling stock for a vote, especially if it is contentious, is a straightforward option for a lender, provided all parties are given enough time. However, this is not always acted on, according to some research reports. International Securities Finance carried out a survey in which 58% of beneficial owners said they did not recall stock to vote; and the Investment Management Association recently released research that showed only two of the 32 investment managers surveyed always recalled stock and seven never recalled stock, with a variety of factors determining the response among the other respondents.

Various measures recommended in Mr Myners’ report have been taken on board or implemented, such as provision of electronic voting and designated accounts for shareholders, but the key to solving the issue with a minimum of fuss is in the hands of the beneficial owners.

Interlinking relationships and timing add up to potential conflicts of interest, so individual situations must be carefully evaluated, says Mr Myners. “Everybody has got these conflicts [of interest]. We can’t lust after a world in which there are no conflicts, but we can best manage them when we’re aware of them,” he says. “One of those questions I have suggested that [pension fund trustees] ask is: ‘Do we understand all of the conflicts of interest that exist around this pension fund?’ Because unless you appreciate their existence you are unlikely to be able to respond when it appears that a conflict could be damaging.”