Growing volumes of orders and trades will require faster processing and increased capacity in both banks and exchanges, says Dan Barnes.

As black box/algorithmic trading pushes data volumes through the roof and venue competition grows, order-processing speed and capacity must be increased to compete in the securities game.

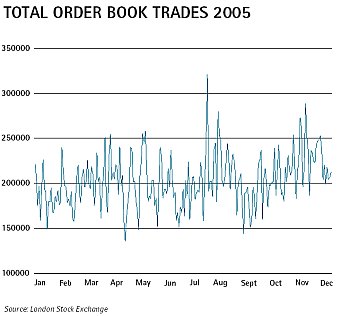

Looking at orders and trades placed on an exchange and at the levels of data running through an investment bank, it is clear that systems’ capacities are being tested to the limit.

In the words of Liam Cheung, senior vice president of strategic development for Penson Worldwide: “It is a problem the entire industry is facing. It’s like a speeding train – you can’t stop the train and it just keeps on accelerating. The exchanges can keep doing one of two things. They can work on the technology – or make changes to the market structure.”

The situation poses a real threat given the technologies currently used, says Simon Garland, chief technology officer at database vendor Kx: “You’ll have systems crashing because they were never designed for this amount of activity – stress is the right word for it.”

Threat to business

Even where capacity problems are being dealt with, the potential for any drop in speed can threaten business. For most industry players, the basic hardware issues around lack of speed, or latency, have been dealt with, such as offices next to the exchange of choice or dedicated cabling.

However, with exchanges themselves facing increased competition thanks in part to regulations such as the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID), they must be certain they can provide traders with the growing service levels demanded.

At a panel discussion hosted by the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX), Penson and Nexa, on October 26, the point was summarised by Doug Clark, director of sales and trading at ITG Canada: “The AMEX [American Stock and Options Exchange] has just created a pricing mechanism that’s going to drive business out because they can’t handle the flow of algorithmic trading. The New York Stock Exchange [NYSE] is desperately slow compared with the Canadian and Nasdaq marketplaces and world marketplaces.

“It’s the bigger exchanges that are having to deal with these latency issues, and they’re going to have to deal with them quickly because the growth in volume and in number of orders is geometric.”

Nexa’s Mr Cheung stresses that the level of work required will vary according to market infrastructure, for example, he says: “The NYSE, TSX and AMEX are chasing a problem of hundreds of messages per second, Nasdaq faces 1000-plus messages per second and OPRA (Options Price Reporting Authority) faces a problem to the level of 100,000 messages per second.”

To avoid the potential risks posed by order and trade volumes, some industry players have been investing in cheaper and newer IT. At the London Stock Exchange (LSE), the technology project Technology Roadmap (TRM) is already bearing fruit.

Roadmap targets

Part of this four-year plan has been the implementation of Infolect, the information delivery system, which replaces the earlier London Market Information Link (LMIL). Crucial targets for the project were the use of commoditised systems such as Microsoft’s .net platform to reduce costs without compromising downtime.

According to David Lester, the LSE’s chief information officer, the results have been a notable success. “The benefits to us of moving from one to the other are that it will allow us to bring our latency down from what we think was already a world standard of 30 milliseconds end-to-end to a latency of an average 2 milliseconds. We believe that’s the fastest exchange information dissemination platform in the world.”

The use of commoditised servers at the LSE is also reducing the cost of increasing capacity at a point when the levels of orders and trades has been reaching critical mass. “Three weeks ago we doubled the capacity of our trading platform. On the last 15 business days we’ve had six of our 20 busiest days ever,” Mr Lester says, at the time of going to press.

“Before, it would cost us literally millions of pounds to scale capacity, now it would cost us several hundred thousand pounds to scale capacity. You can imagine the customer and business benefits in that. As machines drive and continue to drive us, then the world continues to get faster and faster, we will be able to respond to that by providing capacity, at a relatively marginal cost.”

Internal issues

For those trading on the exchanges (assuming that hardware has been fully optimised), internal systems have to be addressed so as to process data as rapidly as possible.

Mr Garland believes that the ‘best execution’ rules of regulations such as MiFID can mean that new risks are being seen that could inhibit trade if data cannot be processed at the necessary speeds and accuracy. “People will ask ‘How different is the data we’re basing this on compared with what we’ve seen over the last week? Does this mean we might be running a regulatory risk?’ So the first people who are able to check data and use it will be able to sail much closer to the wind and make deals that others wouldn’t take a risk on,” he says.

If there is a high level of latency internally, the data will not reach the trading program within the bank before the competition. “It takes so long to get out to the program that is going to decide whether to make a buy decision; then you need to ask ‘shall we take the risk?’ The 20 other people in the market will jump in there too. You’ve blown it.”