The UK has placed Africa and the environment at the forefront of its international agenda for this year, when it chairs the G8 grouping of leading industrialised economies, and there are reasons to believe that real progress may be achieved. While consensus remains far off on green issues, there are signs that agreement on helping Africa financially is within negotiating reach and debt appears to be the main issue on which a deal may become possible.

The US, however, has said that it is not prepared to join the proposed International Financing Facility, which would raise money rapidly for Africa on the capital markets to be repaid over the long term by rich countries. In addition, progress towards a deal on world trade reform, which is another key issue for sub-Saharan countries, has been painfully slow.

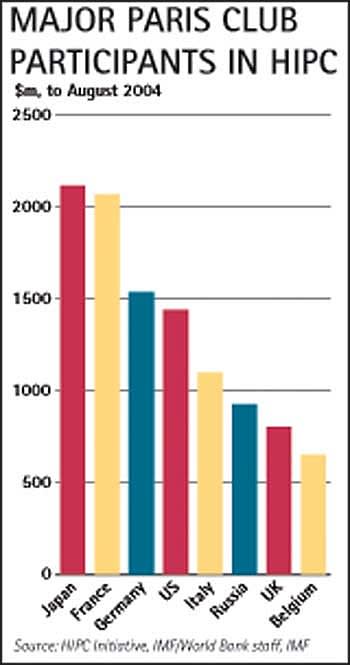

In contrast, there are real chances of a breakthrough towards the UK goal of achieving 100% cancellation of debt to multilateral institutions.

Debt doubters

Some European countries, such as France, have had deep reservations about this, believing that it is a diversion from the bigger challenge of mobilising vast sums of new aid money. The latter is a question that will have to be confronted when world leaders gather in September in New York to review ways of accelerating the slow pace of advance towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), such as halving the number of people on the planet who live in extreme poverty.

The doubters may be won round to action on debt as a useful, if modest, step provided arrangements can be structured to shield the financial integrity of the World Bank, and especially the IMF.

The UK has suggested selling some of the IMF’s $42bn gold reserves to finance an increase in the level of heavily indebted poor countries’ (HIPC) debt relief up to 100%.

It is affordable

The UK also wants donors to pay off the residual balance on debts to the World Bank’s soft-lending International Development Association (IDA) and African Development Bank (ADB) that have already been reduced under the HIPC initiative. It has committed itself to setting an example, paying about 10% of the outstanding balances (proportionate to its weight as a Bretton Woods shareholder).

A respected non-governmental organisation (NGO), Eurodad, believes that the World Bank could afford to take $10bn from its general reserves to finance extra debt cancellation without remotely jeopardising its prized AAA credit status.

The report of the Africa Commission, set up by UK prime minister Tony Blair, says that the cost of providing 100% relief for all sub-Saharan countries would be only $2bn a year. It argues that debt relief should be broadened to countries outside existing schemes and points out that Nigeria, which has a low average per capita income despite its oil resources, paid $1.6bn in debt service in 2003.

Argument for aid

Not everyone is convinced. The French view is that it would be more logical to increase aid. Germany’s Bundesbank (central bank) recently issued a public warning against selling off the part of the IMF’s gold reserves to finance debt relief. The Bundesbank said that, technically, the gold belonged to shareholder governments and that it should be kept to underpin the credibility of the IMF’s capacity to withstand a major default by a borrowing member state.

Beyond the fine haggling over the usefulness of 100% relief are much more fundamental, almost philosophical, questions. Should debt relief be designed only to help restore macro-economic stability – in other words, to put countries in the position they might have reached had they not fallen into payment problems? Or should it be a more ambitious exercise, designed to contribute resources towards reducing poverty and improving essential services for the populations of poor countries? If the latter is the case, how do you define the limits of relief? Most sub-Saharan countries are in the “least developed” income bracket, with widespread poverty and health and education services falling far short of what most middle or upper income countries would regard as acceptable.

HIPC relief programme

The main instrument of debt relief that is applied to Africa, the HIPC initiative, is founded on the principle of restoring macro-economic balance or stability. The level of relief that is granted to a debt country is calculated on the basis of an IMF assessment of “debt sustainability” and, in calculating how much debt service a country can support, the IMF essentially analyses its current account position.

For some time, NGO campaign groups, such as the Brussels-based Eurodad, have been arguing that it would make more sense to decide how much relief was needed to allow countries to finance their long term poverty reduction programmes properly. These issues will come to a head if – probably at the behest of the UK and other Europeans – the question of debt relief for Nigeria is put on the table. Nigeria is a low-income country, measured in per capita GDP, because of its population of 120 million. Because of its oil revenues, however, it does not qualify for HIPC relief under the current terms of the scheme.

Nigeria’s stumbling block

At today’s oil prices, Nigeria does not have a balance of payments problem. However, it does have huge development requirements. In the 1990s, the UN Development Programme calculated that if Bornu state, in the far north-east, was a state in its own right, it would be the world’s poorest country. For years, President Olusegun Obasanjo has been demanding relief on Nigeria’s debts; so far in vain.

The country now has a credible poverty reduction programme, the Needs programme, which has been firmly endorsed by the Bretton Woods institutions. It can credibly show how the benefits of debt relief could be deployed to reduce poverty and develop at the grassroots level. Needs is already being funded out of the country’s own revenues. But, with Nigeria containing the largest concentration of poor people in Africa, should it be accelerated?

Creditor governments in the Paris Club have recently agreed hefty debt cuts for Iraq, which is probably no poorer than Nigeria and will almost certainly soon be much richer. Nigeria will therefore be an interesting test for the creditor community to contemplate, especially as the evidence of the past few years shows that most African countries that have benefited from HIPC have made decisive progress in terms of economic growth and improvements in essential services for the poor.

How far the financial benefits of debt relief are responsible for this is a less certain question. It is arguable that the gains are less the result of the debt relief than the measures that accompany it and to which it is tied.

To qualify for HIPC relief, a country must prepare a detailed strategy for reducing poverty, which has to be approved by the IMF and World Bank and then becomes a roadmap for both national policy and support by the donors. The process of preparing such a detailed plan, and analysing how to translate macro-economic growth into higher living standards and better health and education services, strengthens a country’s institutions and helps to instil a culture of analysis and forward planning.

In terms of financial credibility, HIPC is also crucial. By the time a country has qualified to enter the initiative (at the so-called “decision point”), then designed and managed a programme for economic reform and poverty reduction for an extended period, under Bretton Woods supervision, and then qualified for relief to be made definitive and irrevocable (the “completion point”), it has established a considerable track record.

Ratings turnaround

Traditionally, countries’ credit standing was damaged if they had to seek debt reduction. But today, ratings agencies and international financial institutions take a more sophisticated view. Completion of the HIPC process is a badge of success and good performance, as well as a means of strengthening a poor country’s credit position.

That does not mean that financial markets are reopened to the poor, though. African governments are under strong pressure from the IMF to steer clear of new debt obligations at commercial or even sub-market rates. That leaves most low-income countries dependent on aid to finance long-term development and, it is now increasingly recognised, most new infrastructure.

That is why, even if Mr Blair and UK chancellor Gordon Brown succeed in persuading fellow G8 leaders of the case for 100% debt relief, the biggest challenges will remain: how to reform world trade to allow Africa to bolster its export earnings and how to mobilise new aid finance for the massive investments required to accelerate progress towards the Millennium Development Goals.