Elections have never been Nigeria’s strong point. It has little experience of them, having been under military rule for most of the period since its independence in 1960. When they have been held, they have tended to be farcical, with violence, intimidation of voters, ballot stuffing and ghost voting all rampant.

The most recent polls in April 2011 were different, however. Although not flawless, they were seen as Nigeria’s fairest yet. Most importantly, few in the country doubt that the president, Goodluck Jonathan, was the legitimate winner. “He has credibility in the eyes of the Nigerian population and the international community,” says Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the new coordinating minister for the economy and finance minister. “That has taken care of a lot of things.”

Team building

Unlike his predecessor, the late Umaru Yar’Adua, who was criticised for delaying reforms, investors are largely confident that Mr Jonathan is determined to tackle vested interests and modernise Nigeria. His cabinet selections exemplified this. He was praised for appointing notable reformers and technocrats to vital portfolios, not least Ms Okonjo-Iweala, who was previously a managing director at the World Bank; Bart Nnaji, who became minister of power; and Akinwumi Adesina, a leading agricultural economist and now agriculture minister.

Editor's choice

These ministers will complement other widely respected officials in charge of the economy, including the central bank governor Sanusi Lamido Sanusi and Arunma Oteh, head of the securities and exchange commission.

“The president went out and got very good people for the cabinet, people with track records,” says Phillips Oduoza, chief executive of United Bank for Africa, Nigeria’s third largest bank by assets. “The economic team in government is one that could bring about a turning point for Nigeria.”

Early promise

The new administration has shown early promise for cleaning up politics and addressing economic problems. One of its first moves was to bring members of the private sector in to the national economic management team, which meets fortnightly and is headed by Mr Jonathan. The president also created a 15-strong implementation arm within the body, which will convene each week under Ms Okonjo-Iweala.

“With this government, there is a real sense of urgency about reforms and desire to listen people who know about running a business in Nigeria,” says a banker in Lagos. “That had been missing in recent years.”

In a bid to boost transparency, the finance ministry recently resumed the publication of monthly allocations to the federal, state and local governments. This practice began in 2004, but soon faded out despite proving popular with Nigerians, who resented officials siphoning off funds they could claim they never received in the first place.

Tighter budget

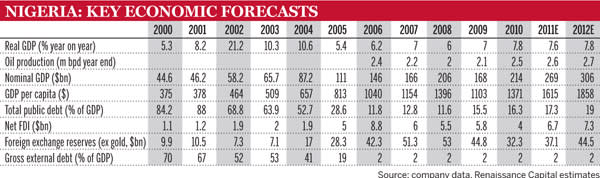

The government has also made clear its intent to end a spending binge, which saw the fiscal deficit climb to 7% of gross domestic product (GDP) last year. Ms Okonjo-Iweala wants it cut to 3% by 2015, when Mr Jonathan’s mandate expires, and is especially eager to slow the growth of public sector wages and overhead costs. “We will set a trend over the next four years of a tighter budget,” she says. “We will try to rein in spending, particularly recurrent spending, which has been growing and is an ever-larger portion of the budget.”

We will try to rein in spending, particularly recurrent spending, which has been growing and is an ever-larger portion of the budget

Domestic borrowing will be curbed. Nigeria’s debt is equivalent to just 18% of GDP – far lower than developed world averages. But naira-denominated liabilities make up 85% of that figure. “We have a little bit more room for external borrowing, but we don’t for domestic borrowing,” says Ms Okonjo-Iweala.

Another priority is the creation of a sovereign wealth fund, a bill for which was signed by the president last year. This has yet to be enacted and still faces opposition from some state governors, who do not want revenues held back from them. But is it expected to be passed in the coming year and be more effective than the excess crude account, which lacked a strong legal structure and was controversially depleted between 2008 and 2010.

Optimum conditions

That these political and fiscal changes are being ushered in when Nigeria is benefiting from high oil prices (it is, along with Angola, Africa’s biggest exporter of the commodity) makes analysts all the more optimistic that they will succeed. “I have never been more confident about the country,” says Wale Tinubu, head of oil company Oando and one of Nigeria’s most high-profile businessmen. “At the point where we are getting the most gains from oil, we are also seriously reforming.”

These reforms should also be helped by Nigeria’s robust macroeconomic situation. Real GDP grew 7.8% in 2010 and is expected to expand about 7.5% in 2011. Inflation fell to 9.3% in August, having been in double digits since 2008. Mr Sanusi says he wants it to reach 5% or less in the medium term, although he cautions that high prices for food and energy imports could hamper his efforts.

The banking sector has been revitalised following its crisis in 2009, which was triggered by a collapse in oil prices and Nigerian stocks a year earlier. The government was forced to pump N600bn ($3.9bn) into failed lenders and take on bad assets, as well as establish tighter regulations following the discovery of widespread accounting fraud and shoddy risk management.

As far as the financial system is concerned, the crisis is behind us... The changes we have made to the industry have been far ahead of the rest of the world

As a result of these actions, most lenders now have capital adequacy ratios well above 15% and have slashed their non-performing loans. “As far as the financial system is concerned, the crisis is behind us,” says Mr Sanusi. “The changes we have made to the industry have been far ahead of the rest of the world.”

Businesses hungry for credit are benefiting from the industry’s renewed health. Segun Agbaje, managing director of Guaranty Trust Bank, says many lenders will expand their loan portfolios by 20% this year, a faster rate than in 2010.

Poverty persists

Despite the economy’s buoyancy, growth has been uneven and is failing to benefit large swathes of Nigerians, 70% of which still live on less than $2 a day. Income inequality has been cited as a cause of militancy in the south-eastern delta region (a threat which has been somewhat subdued since an amnesty in 2009) and even Islamic extremism in the north of the country. The rise of the latter was demonstrated in August when Boko Haram, a group based in the north-eastern state of Borno and believed to have links with Al-Qaeda, suicide-bombed the United Nations headquarters in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, killing 23 people.

Politicians insist that tackling poverty is one of the main aims of Mr Jonathan’s reforms. “The worry is that the growth we have had has not been creating enough jobs for the population,” says Ms Okonjo-Iweala. “That is a challenge that we obviously need to work on.”

Diversifying the economy from oil will be crucial to achieving this. The federal government derives 80% of its revenues and 95% of export earnings from the commodity, the production of which creates little employment relative to sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture.

There has been progress in recent years and non-oil industries are causing most of the current increase in economic output. The services sector is thriving thanks to a rapidly growing middle class. The insurance industry, for one, is expanding faster than the economy itself, says Wale Onaolapo, head of Sovereign Trust Insurance, a local firm.

The telecoms sector has also risen spectacularly. Only 700,000 Nigerians had mobile phones 15 years ago. In 2011, 80 million do, making the country one of the world’s largest such markets. Bankers say the industry’s success is testament to Nigeria’s huge economic potential. “What has happened in telecoms could happen in any other sector of the economy,” says Bola Adesola, chief executive of Standard Chartered in the country.

Reaping potential

Other parts of the economy are far less developed, however. Agriculture is Nigeria’s biggest employer and makes up 40% of GDP. Yet it has been largely neglected since oil production started in the late 1950s. Only half the country’s 65 million hectares of arable land are cultivated, says Olusegun Aganga, minister of trade and investment. And productivity is low due to a lack of large-scale commercial farming and irrigation.

Development is partly hindered by tight funding. Despite the sector’s size, it makes up just 1.5% of banks’ portfolios, due to the risks involved in lending to farmers. But its potential is clear from the fact that it is still growing 7% to 8% annually. “That is on its own,” says Jibril Aku, head of Ecobank Nigeria. “Imagine what could happen if banks tripled their loans to the sector.”

Banks are far from being solely to blame, however. Getting them to expand their provision of credit without developing support industries would simply create bad loans. “How do you lend to a tomato farmer if 40% to 50% of his output is lost between the farm and the market because there is no investment in storage and logistics?” says Mr Sanusi. “When the value chains are fixed, we will get the banks lending.”

With a growing population and rising import bill for staple foods that can be produced locally, there are huge opportunities for growth in agriculture

The Central Bank of Nigeria set up a N200bn ($1.28bn) agriculture fund two years ago to boost lending to all parts of the sector, including farming, processing, storage and marketing. If successful, it could enable Nigeria to become self-sufficient in the production of food crops such as rice, and reduce its imports. “With a growing population and rising import bill for staple foods that can be produced locally, there are huge opportunities for growth in agriculture,” says Bisi Onasanya, managing director of First Bank, the country’s largest bank.

A natural step

Nigeria has plenty of natural resources other than oil. But, much like agriculture, they have been overlooked in recent decades. This is changing, however. Iron ore is set to be exported for the first time in 2012 and production of coal and gold should start in the next few years.

As part of efforts to bolster the sector, the government is trying to lure foreign mining companies and has established what it says is one of the world’s most competitive tax regimes for the industry.

Manufacturing is one of the least sophisticated parts of Nigeria’s economy. In spite of so many inputs being available locally, it accounts for just 4.5% of GDP. “That is not good enough for a country that has all the raw materials we do,” says minister of trade and investment Mr Aganga. “The aim is to double that in the next four to five years.”

The government plans to boost manufacturing by exploiting Nigeria’s minerals. As well as being exported, iron ore will be sold locally to establish a steel industry, which in turn can tap into the country’s vast population of 155 million – the biggest in Africa – to sell products.

Nigeria has already set a precedent for this. Its deposits of limestone have been used to create a booming domestic cement industry. It is expected to become a net exporter of the building material next year. “We have to export our minerals, but also do the value-added bits [locally], because we want to grow our industries around areas in which we have a comparative advantage,” says Mr Aganga. “Having the raw materials will make it easier to become globally competitive in these.”

In the pipeline

Little will be achieved if infrastructure is not improved, however. The quality of transport networks is poor in most parts of the country. But the worst problem is power supply. Nigeria generates a paltry 4000 megawatts (MW) of electricity. Brazil, which has a population of 195 million, generates 100,000MW, while South Africa produces 37,000MW for its 50 million people.

Six out of every 10 Nigerians do not have access to electricity and even for those that do, power cuts are frequent. Small businesses suffer particularly badly. “How many can be commercially viable if they have to provide their own power?” says Mr Sanusi. “If you look at the typical balance sheet of a small Nigerian company, a lot of money is not spent on its core business. They are buying generators and diesel [to run them].”

Mr Jonathan has staked a lot on his ability to increase electricity production. He wants to triple capacity by 2013 and aims to do it by privatising generation and distribution companies.

Wasteful processes

Poor infrastructure is also the reason that Nigeria, despite producing 2 million barrels of oil each day, imports almost all its fuel. Its refining capacity is tiny. Oando’s Mr Tinubu says this will continue to be the case as long as fuel subsidies remain in place. Few companies are likely to invest billions of dollars building refineries when their revenues would be dependent on government payouts of subsidies, which are often made late.

Nigeria also flares enormous volumes of natural gas – enough to power most of Africa, some believe – because few facilities exist to distribute it to businesses and homes across the country (although companies such as Oando have started building gas pipelines in the south).

Postponing development

Bureaucracy and corruption are other major factors suffocating attempts to diversify the economy. They are, along with lack of access to financing, viewed as the biggest impediments to doing business in Nigeria. They are largely responsible for Nigeria ranking 127 out of 142 countries in a survey of competitiveness carried out the World Economic Forum in September.

Mr Tinubu comments on the prevalence of bureaucracy, saying: “We have had projects delayed for two years while waiting for approvals that should take two months,” referring to a $150m gas pipeline project that created 5000 jobs. “It should have benefited the economy two years sooner. We are effectively postponing our own development.”

Nigeria’s economic potential is vast. It has the seventh largest population in the world and raw materials in abundance. Such is its clout that investors wanting exposure to the continent will always look towards it. “If you are not in Nigeria, you are not in Africa,” says Ms Okonjo-Iweala.

Problems such as poverty, graft and weak infrastructure are deeply entrenched and will take years to solve. But this year’s elections and the putting together of a highly regarded team of experts to take charge of the economy have greatly boosted Nigeria’s standing abroad. They have also given Nigerians hope that, with the help of rapid growth, their leaders will finally implement the reforms needed to establish a modern, sophisticated economy.