Algeria is one of the world’s gas powerhouses. It ranks 10th globally for both reserves and production, and its output is the highest in Africa. It is also the continent’s third largest oil producer.

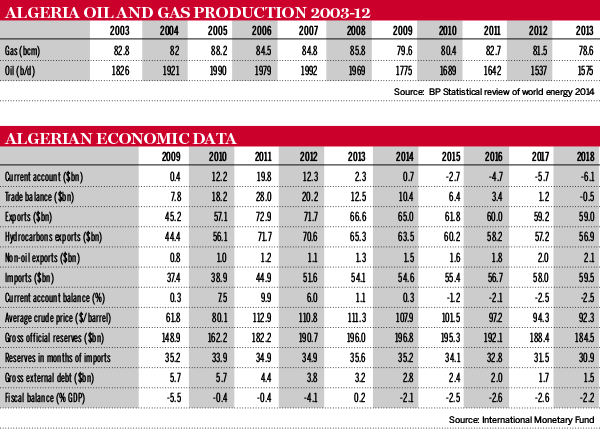

But, having peaked in 2005, Algeria’s oil and gas output has been steadily declining. Gas production was 79 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2013, down 11% from 2005. Oil production was 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2013, down from 2 million bpd in 2005, according to BP’s latest review of world energy, published in June 2014.

Downward spiral

Even more worrying for Algeria is that exploration efforts have also slowed considerably. In 2005, the energy ministry outlined ambitious plans to hold an international licensing round at least once a year, and ideally twice. But there have only been three rounds since, and these have failed to generate much excitement among foreign companies.

The global economic downturn has scarcely helped. But the bigger problem is the difficult operating environment for international oil companies (IOCs), which have suffered as a result of the country's onerous and unexpected regulatory changes. In 2006, the government reversed liberalisation measures introduced just a year earlier and brought in a punishing windfall tax on output from existing oil producers. Moreover, a terrorist attack on BP’s In Amenas gas facility in January 2013, in which 39 expatriate workers were killed, fundamentally altered the country’s risk profile.

Early last year, the government sought to reverse the decline in interest with another set of amendments to the hydrocarbons law. These are aimed at making it more appealing for companies to explore and develop unconventional resources. At the centre of the changes was a measure to tax IOC profits rather than revenues.

The government hoped this would spur renewed interest in a sector that needs advanced technology to tap reserves that are increasingly difficult to access. Many existing fields are old and past their peak production phases: the largest oilfield in the country, Hassi Messaoud, and the largest gas field, Hassi R’Mel, were both discovered in the 1950s.

Push for shale

Officials also hoped the law changes would encourage the development of the country’s promising shale gas reserves. According to a study by the US government’s Energy Information Administration, Algeria has estimated recoverable shale gas reserves of 20,000 billion cubic metres, more than any other country other than China and Argentina, although only a fraction of these are thought to be commercially viable.

Early indications of the success of the legal amendments have been mixed. When the Algerian government’s oil licensing body launched its fourth international bid round earlier this year, some 40 IOCs expressed interest. But the deadline for formal bids has been delayed twice, from early August to late September, after The Banker went to press. Contracts are due to be awarded on October 29, 2014.

The delays to the schedule suggest that the government is struggling to attract enough interest in the concessions, although its willingness to allow more time to discuss the contracts is a sign, say foreign businessmen, that it is at least prepared to listen to the concerns of IOCs.

The decision in late-July to dismiss Abdelhamid Zerguine, head of Algeria’s state energy company Sonatrach, and replace him with an interim president, Said Sahnoun, did little to assure IOCs of a stable and consistent oil regime in the country. Mr Zerguine had been in his role since 2011, and it was only in recent months that the sector had finally begun to restore some sense of order after a major corruption scandal in 2010 that led to the dismissal of Sonatrach’s entire senior management.

Even if the licensing round is eventually a success, it will be several years before it results in any production. In the meantime, local demand is rapidly increasing. Between 2003 and 2013, domestic gas consumption increased by more than 50%, from 21bcm to 32bcm.

Shale gas is unlikely to benefit Algeria for a while yet. Extracting it requires hundreds of wells, a road network to support their construction, operation and maintenance, a well-developed local market for subcontracting and logistics, and an abundant supply of water. Algeria has aquifers that can supply water, but strenuous environmental measures would need to be put in place to assure that the country’s underground reservoirs were not contaminated by the chemicals used in the drilling process.

Poor track record

Algeria’s track record in delivering more straightforward projects does not bode well for taking on the challenge of shale. “It takes about 18 years to develop a conventional oil and gas project in Algeria,” says Michael Willis, an Algeria expert at the University of Oxford. “It takes such an enormous amount of time between the discovery of the resource and making it pay that the likelihood of shale production, even in 50 years, is not that strong.”

There are a few new gas projects due to come onstream in the next five years, particularly in the south-west of the country, but they are unlikely to do more than keep pace with rising domestic demand, say experts. It is increasingly likely that the hike in gas exports that Algeria has been hoping for since 2005 will never materialise, and sooner or later the government will have to face the consequences.

For the moment, government finances are in good shape. The country has some $200bn in foreign reserves and an estimated $70bn in an oil stabilisation fund, the Fonds de régulation des recettes. Economic growth is about 3%, and is expected to increase to an average of 4.3% over the next five years, according to an International Monetary Fund (IMF) report from February.

But, Algeria’s dependence on hydrocarbons is troubling, say analysts. The economy, Africa’s fourth largest, is almost exclusively driven by public spending funded by oil and gas earnings, which account for 97% of export revenues. And hydrocarbon earnings are expected to decline from $72bn in 2011 to $64bn in 2014 and to $57bn in 2018, according to the IMF.

The government has consistently extolled the virtues of diversification and import substitution, but has failed to deliver on its promises of economic reform. Imports increased to $54bn in 2013 from $37bn in 2009, and the IMF predicts that they will reach $60bn by 2018. The promotion of domestic industry is at the heart of the government’s development plans, but industrial growth has averaged just 1% a year for the past three years, according to government figures.

Tough environment

Meanwhile, the regulatory environment for overseas investment has stiffened. In 2009, the Algerian government introduced a regulation limiting foreign investors to a minority stake in local joint ventures, there are tight rules on the repatriation of dividends, and the state has the first right of purchase of any foreign assets up for sale. Perhaps unsurprisingly, foreign direct investment in 2013 amounted to just $1.7bn.

“It’s very difficult for a foreign investor to accept investing where they don’t have a majority of the capital and control of the company,” says a senior banking executive with knowledge of Algeria. “I don’t see any evidence of the law changing in the near future.”

The state’s continued reliance on declining oil and gas earnings is ominous for the country’s fiscal accounts. According to the IMF, the government will run a deficit of 2.1% to 2.6% for the next five years, and foreign currency reserves are forecast to decline to $185bn by 2018. The current account surplus has already dropped from $19.8bn in 2011. It is forecast to be $700m this year and turn into a deficit of $6.1bn by 2018.

A failure to develop local industry has left the Algerian economy with serious structural problems. Unemployment is running at close to 10%, and joblessness in the under-30 age group stands at an estimated 25%. Many Algerians are reliant on costly government subsidies of food, fuel and electricity to stay above the poverty line. For the time being, these subsidies help maintain social stability, but once oil earnings begin to decline this delicate balance could be disrupted.

The development of the private sector is crucial to Algeria’s long-term future, but any such efforts are stymied by the economic interests of the country’s powerful elite. “There are probably a lot of officials in the country that are very interested in the preservation of the public sector,” says the banking executive. “The larger the public sector, the more they benefit.”