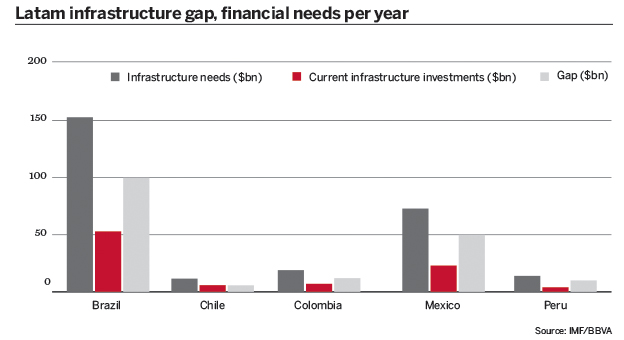

Latin America has a notoriously large infrastructure gap, and to fill it individual governments would have to ramp up their annual spend by tens of billion of dollars. This means that in most countries, attracting private sector funds is essential. But while most countries have made progress in improving the international appeal of their infrastructure programmes by updating legal frameworks and softening certain risks, a series of external issues are now threatening to undo much of this good work.

Lower commodities prices are – directly or indirectly – affecting most of the infrastructure projects currently operational in Latin America, as well as the cash-flow projections of those in the pipeline. The income of these projects is often tied to trade and commodities-related activities, while the economic pressures on the companies carrying out these projects are making it harder to repay financial obligations, even in cases where governments have provided extra financial coverage during the early stages of development. However, reduced tax revenues because of the slump in the prices of oil and raw materials are raising doubts over governments’ ability to provide such financial support in the future.

“Because of lower commodity prices that [negatively] affect most countries in the region, finding projects that are profitable is more difficult now,” says Renato Lulia, chief executive of Itaú BBA International, the international arm of Brazilian investment bank Itaú BBA. No transactions have been closed so far this year, according to data provider Dealogic.

Brazil and Colombia

Brazil’s case is most worrying, as its infrastructure gap is by far the largest in the region, requiring an additional annual spend of $100bn according to Spanish lender BBVA. The country's far-reaching recession and ongoing high-profile corruption scandal has created a climate of uncertainty that has paralysed the activity of many of its businesses and investors. The government is attempting to rein in its public spending, which has traditionally included heavily subsidised interest rates and a large infrastructure lending mandate for Brazil’s development bank, BNDES, as well as for public sector bank Banco do Brasil.

“In Brazil, in the past [infrastructure projects] relied on BNDES or Banco do Brasil, but with the current fiscal policy it’s become more difficult. Last year was one of the lowest in terms of [public sector] investment in infrastructure: 18% of gross domestic product. It is typically 40%,” says Mr Lulia.

Although not as dramatically as in Brazil, matters have deteriorated in Colombia too. Its infrastructure gap is still substantial, however, and its government’s finances have been hit by low oil prices, just as the country launched an ambitious round of road concessions, known as ‘fourth generation’ or 4G.

The first three projects of this scheme reached financial close in 2015, with two others currently nearing that stage, but the overall financing requirements for the programme comes to more than $20bn across more than 40 concessions. To attract private sector lenders to its latest programme, the government has committed to subsidising projects, but reduced public revenues are making lenders nervous. Interest rates have been on the rise in Colombia too, with the benchmark rate now at 6.25%.

"Colombia's 4G programme is very ambitious. When you put 15 or 20 concessions on the market at the same time, and the concessions include traffic risk, you need public sector support to secure bank financing," says Miguel Angel Fernandez Abad, BBVA’s head of project finance in Latin America. He adds that while the market is confident that Colombia will remain solvent on its infrastructure programme, lower oil revenues are a concern.

The government’s previous road concession programmes, the second- and third-generation programmes, were fraught with delays, corruption and financing shortfalls. The Girardot toll road expansion project in Bogotá, for example, suffered severe setbacks and eventually defaulted on its debt in 2004.

A move to markets

Financing infrastructure has seemingly become less appealing for banks across the world. Because of higher bank capital constraints, bank finance to infrastructure has moved from long-term financing to a combination of bridge loans and then a structuring of bonds for the local and international capital markets.

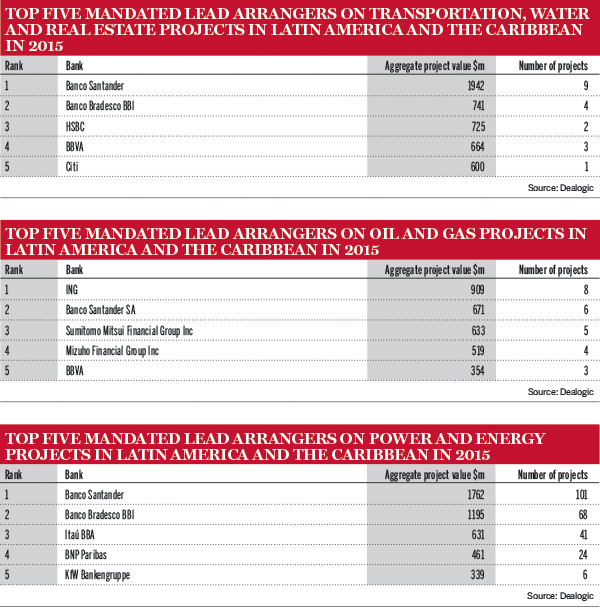

This is becoming the preferred solution for the vast majority of international lenders. Carlos Muñiz, head of global structured debt at Santander, says: “It is not [just] about Latin America; it is about the whole industry of infrastructure financing as banking regulation is putting pressure on the asset class for banks.”

BBVA’s head of project finance in Latin America, Miguel Angel Fernandez Abad, adds: "Historically, infrastructure projects used to be financed over 15 to 20 years [by banks]. They would cover the construction and the operation phases of the project. Now, banks tend to finance the project construction for up to two or three years after construction and they then switch to the capital markets for financing.”

Mr Fernandez Abed adds that lenders are looking for short- or medium-term structures such as mini perms, which typically have a seven-year maturity, or bridge-to-bond loans. This is an opinion echoed by others, with Itaú's Mr Lulia noting that “banks have neither the balance sheet nor the appetite for [long-term infrastructure finance].”

Tough competition

However, while banks are readjusting their participation in the infrastructure sector, Latin America has continued to provide groundbreaking projects that attracted large syndications. The $3bn revolving credit line coordinated by Citi, HSBC and JPMorgan for Mexico City’s $13bn international airport is one such example, as is the $1.9bn financing for the $5.7bn Line 2 Metrorail development in Lima.

There is a further aggravation, however, as lower commodities prices and higher interest rates make it harder for infrastructure bonds to attract local investors. Because of banks’ reticence to provide long-term lending, capital markets are required to substitute the initial shorter term finance with infrastructure bonds.

But simpler investments that often provide better returns are tough competition, particularly for local investors (whose involvement is often crucial, as they are able to provide local currency financing, which is essential for road and energy projects where revenues are in local currency). Convincing local investors to soak up infrastructure bonds has become a harder proposition, considering the novelty that the sector presents to local investors. Brazil’s case is again indicative: despite tax breaks offered to investors in reais-denominated infrastructure bonds a few years ago, the central bank’s benchmark interest rate of 14,25% makes sovereign debt too obvious a choice for large investors.

Institutional investment

As a long-term fixed-rate asset that offers stable returns, infrastructure is theoretically attractive to institutional investors, but it requires specialist knowledge, this is still unfamiliar territory for many such investors in Latin America.

Brazil’s pension funds manage assets that total the equivalent of 16.1% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP), but the equivalent of only 0.1% of its GDP is dedicated to infrastructure. In Chile, a market well know for its developed financial markets, pension fund assets represents a much larger 69.5% of GDP, but even here infrastructure sums up to only 0.6%. Mexico’s pension funds do marginally better, with 0.7%, while in Peru and Colombia, the same figure represents 0.4% and 0.2% of GDP, respectively, according to research by BBVA.

In many cases, governments’ infrastructure programmes have been going hand in hand with the creation of new investment rules and solutions for pension funds.

Brazil’s local currency infrastructure bonds, or debentures, have stalled because of the rise in interest rates, but they remain a strong addition to the local capital markets and their validity will be reconfirmed once market conditions begin to improve, according to many market watchers. Mexico has allowed infrastructure investments through 'fibras', funds that specialise in the acquisition, construction and financing of infrastructure and real estate. The country has also opened other asset classes to infrastructure, such as the certificados the capital de desarollo, or CKDs, among other initiatives.

In Peru, the nascent pension fund market has a high degree of flexibility and does not have a specified quantitative limit on infrastructure investments. And in Colombia, developments in infrastructure bonds and the creation of a fund backed by development bank CAF is helping build the foundations for a more active role by regional pension funds. As of 2014, Colombia’s pension funds are allowed to invest in debt instruments including the ones issued by an infrastructure project company.

Hopes for progress

Bankers hope that the current economic situation will not delay progress being made in capital markets as well as in investment communities. These will be necessary as banking rules have changed the way in which lenders’ infrastructure financing operates. They also open up new business opportunities, as a larger reliance on bonds and other capital market products means a larger demand for structuring skills – something that banks are best placed to offer.

Mr Fernandez Abad says: "Pension funds, insurance companies [and] bond investors; these are the investors that will play an important role [in infrastructure finance in the future]. Banks will continue to build financial structures and once projects are operational, infrastructure bonds will routinely replace bank finance."