Despite ideological differences with president Evo Morales and his Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) ruling party, Bolivia’s banking system – comprising 13 commercial or full-service banks and 11 small and medium-sized enterprise (SME)- and microfinance-focused banks – is generally in rude health: solvent, liquid and well-capitalised. Indeed, the system’s overall capital adequacy ratio stood at 12.1% at the end of 2015, with all the major banks above the regulatory minimum of 10%, according to the country’s financial supervisor, the Autoridad de Supervision de Sistema Financiero (ASFI).

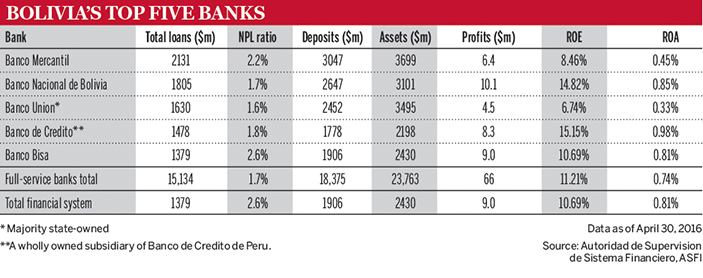

The strong expansion of the national economy and a pragmatic relationship between the government and the financial sector have also resulted in credit and deposit levels breaking records year after year, while delinquency rates remain low (see chart). Meanwhile, the risks associated with the dollarisation of deposits and credits have steadily diminished, with 84% of deposits and 95% of loans denominated in the domestic Boliviano currency at the end of December 2015.

Prudent policies

Added to that, the government has adhered to very prudent macroeconomic management, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and central bank policies have so far been successful in stabilising the exchange rate (Bolivia does not have a free exchange rate policy) and controlling inflation.

Alberto Valdes is the executive vice-president of Banco Mercantil Santa Cruz, the country’s largest full-service bank, which acquired the Bolivian assets of Spain’s Banco Santander in 2006 and now generates about 70% of its earnings from retail and 30% from commercial banking. He says: “Last year in Bolivia, inflation was about 3% and growth was about 5%. That’s not seen in too many places around the region today.”

Tomas Barrios is the CEO of Banco Bisa, the fourth largest bank in Bolivia by assets, which, in contrast to Banco Mercantil, derives 60% of its earnings from commercial lending and 40% from retail banking. He is also optimistic, saying that because of the country's massive $48.5bn 2016-2020 national economic and social development plan (55% financed by national and local governments and the central bank) there will be opportunities for banks in major projects in plastics, infrastructure, hospital building, mining, electricity and manufacturing and food industries.

“We think the expectations for growth in the country are positive and much better than in other countries in the region,” says Mr Barrios.

Challenges loom

But like the storm clouds shrouding the peak of Mount Illimani, which towers over Bolivian capital La Paz, looming challenges are already testing the resilience of the country’s banking system, especially the smaller niche and microfinance banks.

One challenge is that while bankers may not have found the environment with Mr Morales’ left-wing government easy, during the past decade the country has nonetheless experienced exceptional political stability. This is a crucial factor for business in what has often been a volatile country in a politically unstable wider region. But commentators and analysts are now expressing concern about how long this stability will last given that Mr Morales and members of his MAS party have declared their intention to repeat February’s referendum, in a bid to reverse a majority ‘no’ vote preventing Mr Morales from standing for re-election in 2019 for a fourth consecutive term.

“We are wondering what is going to happen,” says Mr Barrios.

There are also economic uncertainties now that the commodity boom has ended (see interview with Bolivian economy minister Luis Alberto Arce on page XX). But the biggest immediate challenge for bankers is the new Financial Services Law (FSL) enacted in August 2013, which aims to preserve financial stability in Bolivia, increase credit for housing and productive sectors and promote financial inclusion.

The law includes provisions to strengthen the safety net and integrity of the financial system, such as setting up a deposit insurance scheme, expanding ASFI’s areas of responsibility and implementing a number of core Basel II and III capital requirement principles. But it also forces banks to be more redistributive, giving the state the power to set deposit rate floors (2%) as well as lending rate ceilings; allocating some of the loan portfolio to productive projects and social housing; and increasing financing in rural Bolivia.

Opening opportunities

Some of the largest banks have found opportunities amid the challenges of the new law when they fit in with existing expertise and businesses. One such example is the new social housing loans, with maximum allowed fixed rates of 5.5% to 6.5%, aimed at making home ownership more accessible to low-income Bolivians. The fixed rates compare with a typical variable mortgage rate of 7.5% to 8% in the free market.

The new law also created guarantee funds from a 6% tax on banks’ 2014 profits, to finance downpayments of up to 50% for productive sector and up to 20% for social housing loans. As a result, Bolivians can now have access to a mortgage even when they cannot afford to make a deposit on an apartment or house.

Notwithstanding these terms – which some bankers consider risky – Mr Valdes says Banco Mercantil Santa Cruz has become Bolivia's “leading bank by far in social housing loans”. He adds: “We have a portfolio of about $450m, representing 23% of our total loan portfolio [$2.2bn] and about 50% of all our mortgage lending. We’ve got a very good grasp on that.”

The other area where the government has set ceilings on lending rates is for productive sectors – broadly defined as non-service sectors, including agriculture, mining, oil and gas, manufacturing, construction, electricity generation and, since July 2015, tourism and intellectual property.

In this area, Banco Bisa, like Banco Mercantil in social housing, has the policies, technology and staff in place to be able to meet the government’s lending quotas. Mr Barrios says: “The allocation to productive sectors [is] not a problem for us because we have always lent to large corporations and recently to SMEs and micro-enterprises as well.”

Commercial banks have until the end of 2018 to direct 60% (50% for SME banks) of their total loan portfolios to social housing, productive sectors and microfinance. Further pressure on banks’ profitability is also coming from taxes. In the past, tax on bank profits was 25% but since 2015 this has been raised to 37%. Taxes on financial transactions have also increased.

In a written statement Antonio Valda, CEO of Banco Nacional de Bolivia, the country’s third largest bank, said: “The FSL regulations on interest rates are inevitably having an impact on banks’ results... and the taxes are having an impact on results too.”

Lower ROE

In terms of return-on-equity (ROE) ratios, the profits of Bolivia’s commercial banks declined from 16.95% at December 2014 to 13.94% a year later, according to the ASFI. In microfinance over the same period, ROE ratios dropped from 18.08% to 16.33%.

Another impact of the FSL is that it is changing the composition of credit flows. Credit to the productive sector and for social housing has increased by about 26% year on year since 2014 but credit growth to non-productive sectors (that is, service, commerce and household) declined to about 13% year on year as of June 2015.

Meanwhile, from 2016 banks are having to set aside at least 50% of their profits as a capital buffer, says Ivette Espinosa, executive director of the ASFI, while meeting social housing and productive sector credit quotas.

Some bankers say such a large capital allocation is not an issue as they have been doing this for years voluntarily. But a December 2015 IMF research paper warns that lower profits and capitalisation in the financial system could reduce funds available for medium-term banking growth, posing a risk for financial stability. IMF researchers also believe, based on other countries’ experience, that the Bolivian government’s 60/40 target by 2018 for social housing and productive sector credit could imply rapid credit growth and risks of an over-concentration of loans, over-indebtedness on the part of borrowers and declining asset quality.

Financial inclusion worries

A more specific concern of smaller microfinance and niche banks is that the FSL’s low 11.5% interest rate ceiling for microloans will thwart progress in financial inclusion.

This is paradoxical. One of the most widely recognised achievements of the Morales administration over the past decade is that Bolivia has achieved some of the world’s highest microfinance penetration rates. Microfinance also constitutes a large part of the business of SME and full-service banks that are either specialists or have microfinance divisions. At the end of March, total invested and operational microcredits amounted to $16.2bn, representing almost 50% of GDP and almost one-third of total credits in the financial system.

According to Ms Espinoza, much of Bolivia’s success in financial inclusion reflects a doubling of financial sales points in poor rural and urban areas in the past 10 years, and the new law will advance financial access further, with more flexible bank opening hours and more flexible repayment terms, she says.

Ceiling criticism

Nevertheless, disappointment among microcredit bankers, especially over the government’s new 11.5% microcredit interest rate ceiling, is palpable.

Consider BancoSol, which has easily the largest market share in microfinance, at 23%, and also provides the lowest average size loans, of $4500, among all microfinance institutions, reaching poorer people. Its CEO, Kurt Koenigfest, says: “We thought we were doing a pretty good job lending at a 17% rate, the lowest interest rate in Latin America for microcredits. We were lending to the informal sector, to street vendors, small agricultural producers, micro businesses in trade, commerce, services.

“The reality is that the new law is pushing our small clients out of our reach. Because at an 11.5% maximum interest rate you cannot do $500 loans in a sustainable way.”

Concurring with this, the IMF’s December 2015 working paper on the Impact of Bolivia’s Financial Services Law on Financial Stability and Inclusion says experience in other countries shows when microfinance interest rates are set too low, poor clients in rural areas are the first to be eliminated because of the higher costs of serving them. Additionally, microfinance institutions in Bolivia are increasing the size of their microloans faster than in other markets, to compensate for the lower rate, the paper says.

However, BancoSol is not following the approach of some competitors of increasing loan sizes, cutting costs and branches, and firing employees, according to Mr Koenigfest. Faced with the new regulations, its CEO and foreign shareholders (Boston-based Accion Internacional is the biggest) have decided to reinvent the bank.

“Today it takes us 10 steps and five forms, paperwork, a loan officer and a risk manager to manually assess a loan and we often have to visit a borrower living in a remote part of the country too,” he says. “How can we cover all of this? With technology – with tablets, phones, communications. So we can reduce the time and expense we incur to do loans effectively. That’s the only way to meet the goal of lending at just 11.5% and still staying solvent.”