When Brazilian bank customers need to access savings from their time deposit accounts, they just go to their nearest branch and convert the funds into a current account. Given the country’s volatile history of inflation and financial crises, no mainstream bank could ever entertain refusing such a request. But now that Brazil has macroeconomic stability, such practices are holding back the development of the country’s mortgage market.

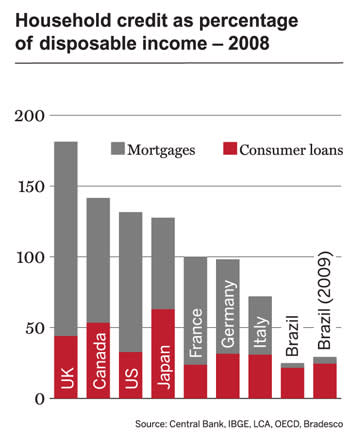

With mortgages accounting for only 4% to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) and making up only a small percentage of banks’ lending portfolios, the potential for growth is huge. This cannot be realised, however, until long-term funding is available and the mentality of always requiring, and obtaining, instant access to cash disappears.

A number of proposals are being looked at to remedy the situation, such as establishing a covered bond market in Brazil, while some other initiatives have already been taken, such as the introduction of 'letras financeiras', a form of fixed-term funding, which is attractive as it allows banks to lower their reserve requirements and has tax benefits as well.

Yet for all these attempts to get the structure right, bankers admit that for full exploitation of the mortgage market in the long term, Brazil must achieve lower interest rates. They are currently among the highest in the world at 12.25%.

Rate conundrum

Right now rates are more likely to go up than down as Brazil battles with inflation at 6%, hot money inflows and an overvalued currency. While raising interest rates would help bring down inflation, the impact would also make the country even more attractive to the carry trade – borrowing at low US dollar interest rates and investing in Brazilian reais – and so send the currency still higher.

The country is also experiencing a consumer credit boom as millions of Brazilians with rising standards of living buy their first car, laptop and other consumer goods and pay by instalments over months or a couple of years. Again with a mentality forged from past inflations, Brazilians do not tend to save much and prefer to spend all their money immediately, often buying on credit. With more than 20% of their disposable incomes eaten up by repayments, some economists worry that a dangerous consumer credit bubble is emerging.

Most Brazilian bankers reject the notion that this consumer credit build up is akin to the US subprime bubble or is in any way dangerous to the system, but they do feel that Brazil may be growing too fast, and hard decisions need to be taken on both interest rates and the fiscal situation.

Sustainable growth

Roberto Setubal, chief executive of Itaú Unibanco, one of Brazil’s big three private banks, takes this view: “At the time of the international financial crisis, the government put a lot of stimulus into the economy both on the fiscal and monetary side, expanding spending and reducing interest rates. The results were quite good and last year Brazil grew at 7%, but [the country] cannot sustain a growth level of 7%.

"Now we are adjusting to a sustainable growth rate, which is about 4% to 5%. For this adjustment we need to cut spending and increase interest rates. We expect inflationary pressures and inflation will probably reach 7% until it gets back on track in 2012. From a technical perspective everything is under control.”

But with huge foreign reserves – Mr Setubal estimates the cost of carrying these at 1% of GDP – interest rate rises have the disadvantage of attracting speculative capital and overvaluing the exchange rate. This has prompted the government to embark on a series of macro-prudential measures aimed at cooling the economy without raising rates. These have included raising the tax on loans, exchange and insurance operations, increases in reserve requirements and higher capital charges for banks on consumer credit loans. The jury is out as to how successful these will be.

Mr Setubal says: “The authorities gave the impression to the market that they would use administrative measures to reduce inflation and the market didn’t like that because, at the end of the day, no one knows how effective these measures will be in controlling inflation. These alone will not do the job; increasing interest rates is the most effective way of controlling inflation.” Rates were raised by quarter of a percentage point to 12.25% in June, the fourth straight increase and the first time there have been four successive increases since 2005.

Development crossroads

In some ways Brazil is at a crossroads in its development. Over the past decade or so there has been a huge transformation with the advent of macroeconomic stability guided by an independent central bank, the free floating of the real, the gaining of investment-grade status for sovereign debt and the build up of reserves. High commodity prices for Brazil’s major exports – soya, iron ore and, over the next few years, oil – have boosted economic growth (although manufactured exports are suffering because of the strong currency).

With Brazil hosting the FIFA football World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016, many are talking about a transformational decade. But if this aspiration is to become a reality and if Brazil is really to progress to the next level of its development, the focus has to switch away from the macroeconomy to many micro and structural issues. These include reform of Brazil’s cumbersome labour laws that cost most banks and large companies about 10% of their payroll in court settlements; reform of the country’s weighty and inefficient tax system that ties up whole corporate departments in form filling and compliance; and the reining in of a sprawling public sector that slows down business with its bureaucratic approvals process, which is a costly drain on government revenues.

To make matters worse, some 80% of government spending is non-discretionary and much of it relates to salaries and pensions that are indexed. There is a complex formula for calculating the minimum wage, for example, that gives next year’s figures based on factors such as GDP growth and inflation. Right now this is set to see a massive 14% uplift in the minimum wage, so fuelling inflation and adding to government expenditure.

For banks the good news is that spreads and returns are so high, with return on equity in the mid-20s for the leading banks, that they can afford these costs and still make very good profits. The same is true for non-performing loans, which are high but do not spoil the overall health of the business. But profits will be hit over the long term if spreads come down without further reforms.

Diversifying the business

Meanwhile the banks are doing what they can to develop new business areas, such as mortgages, within the current environment. They are diversifying their businesses and looking at overseas opportunities as a way of maintaining high returns into the future. State-owned Banco do Brasil recently bought Florida-based EuroBank for $6m as part of a strategy of increasing its overseas income from the current 1% of total to 10% by 2016.

Banco do Brasil CEO Aldemir Bendine says: “It’s important for the bank to grow abroad. Our international strategy is based on three pillars. The first is to be present in countries having high trade finance volumes with Brazil. The second is to follow and serve Brazilian companies as they move abroad to buy assets; currently there are 400 Brazilian companies producing overseas. Third, we want to gain the business of Brazilians living abroad both in retail and remittances.”

In the US, Banco do Brasil already has corporate and securities operations, but needed a retail platform to serve the 1.4 million Brazilians living there, mainly concentrated in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Florida. It hired Royal Bank of Canada to search for a suitable target and, from a list of 17 possible acquisitions, EuroBank was the best match, being based in Florida, with good IT with Portuguese language functions.

Other plans overseas include setting up a holding company together with the Portuguese bank Banco Espírito Santo and Brazilian private sector bank Bradesco to hold African assets and develop opportunities there, particularly in Portuguese-speaking territories such as Angola and Mozambique. Mr Bendine says that Banco do Brasil is also considering buying a Portuguese bank and is looking at a number of targets.

Foreign investment

But as Brazilian banks look overseas, preparing for the day when returns will come down in their home market, so leading international private equity firms are busy setting up in Brazil and are looking at financial sector opportunities as a way of getting a slice of the high growth and high returns in the country.

UK private equity firm Actis, for example, has as one of its three investments in Brazil a minority stake in broker XP, and is also looking at buying into a bank.

Actis partner Patrick Ledoux said in an interview conducted at the World Economic Forum’s Latin American conference in Rio de Janeiro in late April: “In Brazil there are 40 million people who do not have a bank account, and out of a population of 190 million only 600,000 or 0.3% of the population invest in the stock market, so there is huge upside for financial services.”

To gain access to the market, private equity firms are likely to target Brazil’s mid-sized banks, accounting for 10% of system assets. Some of the players have been buffeted by the financial crisis and squeezed still further by the recent administrative measures to cool down the economy. A Fitch report says: “While the system’s larger banks were able to perform fairly steadily through the crisis, the segment most affected by the markets’ volatility was the mid-sized and smaller banks.”

Recent developments

There have been a number of recent developments. US private equity firm Warburg Pincus took a 22.68% stake in the Brazilian medium-sized bank Banco Indusval earlier this year. Schahin is being bought by Banco BMG for about 230m reais ($145m), with Fundo Garantidor de Créditos, the nation’s bank-deposit fund, providing credit guarantees to facilitate the acquisition. The central bank took control of Morada because it did not comply with capital requirements, while a controlling stake in Panamericano, the subject of a fraud investigation, has been taken by investment bank BTG Pactual (see Agenda interview with BTG Pactual CEO Andre Esteves).

The irony is that while it is the mid-sized sector that is struggling, some of the big innovations in Brazilian banking have come from these institutions, such as the development of 'consignado' loans secured by salaries. Larger institutions often purchased these loans from the mid-sized banks as a way into the market before establishing their own presence. Indeed, some mid-sized banks have been struggling with funding since the market for selling credit portfolios dried up.

The challenge for the major Brazilian banks, if they are to maintain their high returns, is to come up with products that can be sold successfully to the country’s low-income segment, to encourage savings and to develop long-term funding for mortgages. They will only be able to achieve all these goals if the government does its part by preserving macroeconomic stability and cutting bureaucracy.

Marcial Portela, CEO of Santander in Brazil, says: “For mortgages the country needs one key thing – lower interest rates. You cannot grow mortgages very fast with interest rates at 12%, it needs to be in the region of 7% to 8%. One of the problems of the financial system is that funding is very short. Now with the authorities we have been involved in trying to find ways to develop long-term funding, such as by issuing covered bonds.

"The average loan duration is probably about one and a half years; 10 years ago it was about seven months. Funding is similar, it is still very short and funding that seems to be long, such as time deposits, can be converted into short-term money. A customer can go to the bank and change a one-year time deposit into a current account. This is a practice that comes from the times of hyperinflation. If we want to develop mortgages and funding for infrastructure, we need long-term funding.”

Mortgage funding

Itaú Unibanco’s Mr Setubal says: “[Mortgage funding] will need to be developed in Brazil, but in a different way. We will not be financing long-term assets with short-term deposits in the way it was done elsewhere in the world.

“Since we are facing this liquidity perspective, and let’s assume mortgages will grow at 40% a year because today they are less than 5% of the total portfolio, and let’s also take account of Basel III liquidity requirements, [then] it’s obvious we cannot use savings or demand deposits to close this gap. That’s why there is a big discussion in Brazil about what would be the right funding for mortgages.

"Given the high level of interest rates this is a problem and this is why Brazil has never developed this before. A lot of current proposals, such as covered bonds, will help but if we don’t have single-digit interest rates it will not happen.”

The first bank to issue letras financeiras, an instrument that was introduced during the crisis to give banks access to longer-term funds in the local bond market, was Banco do Brasil.

Banco do Brasil's Mr Bendine says: “Long-term funding is a challenge for Brazilian banks but we do have some sources, such as savings accounts, which [are] a commodity and the banks all pay the same rates; 6% plus inflation [as stipulated by government].

“Letras financeiras can also provide long-term funding. It is like a local bond that has a good return and allows the banks to issue with benefits in terms of reserve requirements. It’s a mechanism used by the government to decrease liquidity from the market and has lower reserve requirements than other sources of funds.”

Mr Bendine adds that Brazil has a housing shortage of 8 million residences and the bank aims to double its mortgage portfolio by the end of the year.

Access to long-term funds

Two other Brazilian state-owned banks have access to long-term funds – the development bank BNDES and the national savings bank Caixa Econômica Federal, which have pension and insurance fund deposits.

The state-owned banks led the lending growth during 2009 when the stimulus was being applied, and as a result increased their total market share from 40% to 45%, according to Fitch. But Mr Bendine is adamant that this was done safely and with widespread use of secure methods, such as consignado lending. Caixa Econômica Federal, doing its part to provide affordable housing during the crisis, launched a housing programme called 'minha casa, minha vida' ('my house, my life').

Rodolfo Spielmann, a partner with the consultancy Bain & Company, says: “Brazilian banks are only just starting to tackle the issue of serving the 70 million to 80 million people at the bottom of the income curve. Everyone is trying to see how best to penetrate it but no one has really cracked the code.”

On the other hand, Brazilian bankers point out that one of the defining features of the past decade has been lifting millions of people out of poverty, as well as the expansion of the middle class.

Citibank’s CEO in Brazil, Gustavo Marin, says that the moving of millions of people out of poverty and into the middle class has boosted consumption. “Consumption was held back in the past, but this consumption has a real economic basis and is not the result of a bubble.”

Santander’s Mr Portela says: “All classes have improved their income levels over the past 10 years. It is not only that millions have moved out of poverty and become middle class, inside the middle class the same process has been going on. So someone who was getting 500 reais per month now gets 1000 reais and the 1000-reais earner became 2000 reais and the 2000-reais earner became 4000 reais.

"One of the problems we have now at the bank is that the upper part of our clientele earning 4000 reais a month and more but not at the private banking service level – this client segment has increased so much that we have difficulties to service them with the standard we have agreed. It’s the best problem we can have but it’s one we have to solve.”

Challenges remain

But dramatic as the improvements are, Brazil cannot afford to rest on its laurels. The overall business climate can be challenging and there are fears that bureaucracy will stand in the way of the construction work needed to host the World Cup and the Olympics.

At the World Economic Forum meeting on Latin America in Rio de Janeiro, one foreign businessman operating in this area said that unless some of these taxes and bureaucratic processes were changed, the work would not be completed on time.

The CEO of Brazilian aircraft manufacturer Embraer, Frederico Fleury Curado, told delegates Brazil was already behind with these projects and that negotiating bureaucracy was a major challenge: “The tax issue is also a major problem and hurts Brazilian companies and is very complex politically. The government has talked about doing a broad reform removing fees on payrolls, federal fees and taxes that could easily be removed or cancelled. This is a major barrier against Brazil really developing its economy.”