In a financial climate that remains uneasy, with many countries still teetering on the edge of an economic abyss, Canadian banks continue to be solid, reliable performers. The country's 'big six' lenders have all achieved good results recently – from the largest lender in the country, Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), which posted a net income for the first quarter of 2011 and showed year-on-year increases of 23%, to the smaller National Bank of Canada, which achieved a record net income of C$312m ($324m) in the first quarter of 2011, a 45% increase on its 2010 results.

The other big six banks are Scotiabank, Toronto-Dominion (TD) Bank, Bank of Montreal and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, which in 2010 suffered losses from its structured credit business, but still posted a first-quarter net income of C$799m, 22.5% up on the previous year.

The Canadian banking sector continues to be one of the most stable and well capitalised in the world, with Tier 1 capital ratios ranging between 11.8% for Scotiabank and almost 14.6% for National Bank of Canada as of the end of January. Its economy is performing strongly, with some of the more optimistic forecasts predicting that real gross domestic product will grow by 3.1% this year.

But despite this seemingly idyllic picture, there may be problems ahead for Canadian banks. Products sold to Canadian consumers are the largest single exposure across Canadian banks and domestic demand is expected to slow due to high consumer debt levels.

Debt problem?

At the end of the third quarter of 2010, Canadians were made aware of their high level of indebtedness as the country's debt-to-income ratio reached 148%, higher than the then 147.2% of the US. This ratio is calculated on an aggregate basis for the whole country and, as of February this year, reached 150%, according to a report by the Vanier Institute of the Family, a Canadian research organisation. The country’s national statistical agency, Statistics Canada, had it at a marginally lower 148.8% in March.

Fears that the debt-to-income ratio signalled that Canadian households were in trouble have been calmed by assurances the ratio does not necessarily show whether consumers are able to keep up with debt payments. Total size is important but is not in itself a problem if debt is structured so that consumers can afford regular repayments.

Statistics Canada’s measure of the country's debt-service ratio, which indicates how much income has to be used for monthly repayments of debt, saw this percentage edging down in the second half of last year and remaining below the historical average, mainly due to Canada's low borrowing rates. Economists at TD Bank researched debt-service ratios across the country earlier this year and reported that, on average, 18.6% of Canadians’ gross monthly pay was spent on debt as of the end of September 2010. In financial communities, alarm bells generally sound when that figure reaches 40%.

Signs of stress

Looking closer at Canadian households, however, there is evidence of stress. Mortgages and credit card loans in arrears were still above pre-crisis levels by the middle of 2010, according to the latest research by Statistics Canada. Arrears of three months or more were about 0.6% and 1.4% of the total for residential mortgage loans and credit card loans, respectively. These may not seem particularly high figures, but they are unusual for the Canadian market.

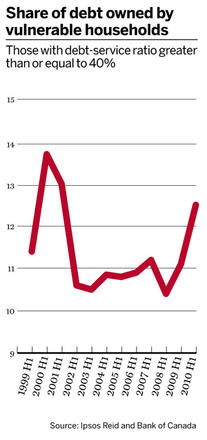

Further, a survey by market research company Ipsos Reid indicates that the proportion of households with high levels of debt has risen and that, in particular, the ones with a debt-servicing ratio of more than 40% have increased significantly since the end of 2008. The percentage of household debt owned by heavily indebted households was almost 12.5% of the total in the first half of 2010, against 10.5% in the second half of 2008.

On their side, Canadian consumers – and lenders – have a cautious mortgage market regulation, which imposes insurance on any mortgage where the loan-to-value ratio is more than 80%. Amortisation periods have also recently been reduced by five years to 30 years for new mortgages that are not insured by governmental agency Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and the maximum amount home owners can borrow on a refinancing deal has gone down from 90% to 85%. This makes the comparison between the Canadian and US level of household indebtedness less meaningful, as the US's mortgage market is not as highly regulated as its neighbour's.

“The biggest differentiator between the Canadian system [and other banking systems] is the mortgage market,” says Gord Nixon, chief executive of RBC. “At the heart of the problem in the US was their mortgage market, while a huge source of strength for the Canadian [banking] system is our mortgage market and its regulation.”

Peter Nerby, lead Canadian banks analyst at rating agency Moody’s, agrees but also points out that the level of consumer indebtedness is the largest single exposure for virtually every Canadian bank. “Something to keep a close eye on,” he says.

Problems with the neighbours?

But if comparisons between the Canadian and US mortgage markets are not particularly meaningful, some Canadian banks that have operations in the US are experiencing problems.

The US is, in fact, the Achilles heel of RBC's international presence when it comes to retail banking. The bank’s retail operations there are the weakest performing of the group and, while other lenders have been looking at seemingly cheap US banking assets to grow their presence in the country, RBC remains focused on fixing its existing business and is wary of the many uncertainties still present in the US.

“There are always acquisition opportunities in the US,” says Mr Nixon. “From a retail point of view, we’ve made it clear that our priority was to get better performance from our existing bank, which is our weakest-performing bank. Until we get better performance and greater clarity on how the US retail banking market is going to unfold, the pressure to do something quickly, in the short term, is not there. There is still lots of uncertainty around the real-estate market, regulation [and] the Dodd-Frank Act. Caution is something we’re not going to be penalised for.”

A more enthusiastic view

But not all lenders share Mr Nixon’s view. Bank of Montreal acquired troubled US lender Marshall & Ilsley for $4.1bn last December, giving the opportunity to Harris Bank, the Canadian bank’s US lender, to expand in the mid-west region. Analysts are reserving judgement on the deal due to the financial difficulties that Marshall & Ilsley had incurred.

A US acquisition that seemed to have been received more enthusiastically by observers is TD Bank’s purchase of Chrysler Financial from private equity fund Cerberus Capital Management for $6.3bn at the end of 2010. The deal has made the Canadian bank one of the five biggest auto lenders in the US. Chrysler Financial changed ownership after its original owner, Chrysler, filed for bankruptcy protection in 2009 and formed an alliance with Italian car manufacturer Fiat.

“TD has done something interesting with the acquisition of Chrysler Financial,” says Moody's Mr Nerby. “TD has a ‘high-class’ problem, which is that it has lots of deposits in the US, so it gets a loan origination capacity to mop up all those deposits.”

But it is not just the US that offers international growth opportunities for Canadian banks. RBC and Scotiabank, in particular, have a growing international presence outside North America, which include both retail and wholesale banking and wealth management.

Scotiabank’s model of growth continues to pay off and chief executive Rick Waugh is proud to point out that its most recent results reflect the good performance of the company's international businesses. “[Last year] was really good to us, we had a record year and that was contributed to not just by our Canadian operations but also by our operations around the world, in Latin America and Asia, and in wholesale banking.” The bank’s 2011 first-quarter net income was also a record figure, at C$1174m, up 18.8% year on year.

RBC's growth by acquisition

RBC has been developing its capital markets and wealth management activities in Europe, from its base in London, and also in Asia. Wealth management in particular is an area where RBC expects greater returns, and where it has been growing by acquisition and not just organically. The bank bought UK-based BlueBay Asset Management in 2010 and took over Canadian firm Phillips, Hager & North Investment Management the previous year.

“Capital is available to all of [our operations] if there are good growth prospects,” says Mr Nixon. “We like that model because we think that it provides good diversification. I’ll be very happy five years from now if all our businesses continued to grow but the mix is the same. I doubt that will happen [as] growth rates are going to be different. Wealth management is the one where we think there are above-average business prospects.”

Capital markets have also been an area of sustained growth for RBC. This time, the US has been a fruitful market for the bank, which has doubled the number of employees in its New York office over the past five years.

Casting a net

International markets offer potential for future growth as Canadian corporates expand their businesses both domestically and abroad. Benoit Daignault, senior vice-president of export credit agency Export Development Canada, says: “Canadian companies are increasingly looking abroad; there is more appetite to go beyond the US and that shows in our results: we supported $10bn-worth of trade and investment between Canada and the Americas last year.”

Another factor in Canada’s favour is the commodities boom and the growing demand from Asia for oil, gas and mining assets. This is true both for Canadian assets and for corporates that have assets in other regions but choose to set up base in Canada to take advantage of the country's banking and financial markets expertise in these sectors.

Canada looks set to continue attracting capital-raising activities, especially for smaller issuers. “Canada is really the epicentre of the junior mining companies,” says Erik Bethel, managing partner of SinoLatin, a firm advising Chinese companies on investment in Latin America. “Many of them are publicly traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange, and many have assets in Latin America.”

Principle-based regulation

Canadian banks’ strong capitalisation and good performance does not make them immune from the worries that preoccupy their less successful peers, however. As discussions over international regulation take place, the expected highly prescriptive rules under Basel III may unsettle Canadian banks that are more used to a principle-based approach to regulation.

“The success of the Canadian banking system was down to good, prudent management, principle-based regulation and conservative capital ratios,” says Mr Waugh. “[It was down to] the risk management and the governance of the management of banks. No rules or regulations by any regulator have ever saved a bank. Good management saves banks.”

Although no bank would argue that strong capitalisation and a control on leverage are not beneficial, Canadian lenders fear that the current discussions over Basel III rules will end up being too prescriptive and counterproductive. RBC’s Mr Nixon has been very vocal about his concerns: “Basel III is important but there is a risk that it will go too far, be too prescriptive and ignore other areas such as ensuring that [certain] national markets are properly regulated,” he says.

“It’s not just the [financial] institutions, it’s the underlying markets in which the institutions are operating. The mortgage market in the US is the best example as this was at the heart of the financial crisis. You have all these reforms of the financial system but you haven’t yet had a reform of the residential mortgage market in the US, which we’re starting to see only now.”

So, the stories that grabbed headlines in recent months – high level of indebtedness of Canadian households and uncertainty over the US market – might not be as big a challenge to banks’ growth as the series of international banking rules created in response to problems originated in other jurisdictions. The concern is that banks would become too restricted in what they were allowed to do, that they would become overly cautious, even by Canadian standards.

“What I worry about is that regulation is so focused on restricting banks' activity [with high requirements for] capital and even prescriptive rules around what banks can and cannot do, that it is going to take some of the innovation and creativity out of banks, which is so important for economic growth,” says Mr Nixon.