Not long after Mexico passed its long-awaited energy reform in December 2013, breaking state-run Pemex’s monopoly in the sector, oil prices tanked, bringing private sector enthusiasm down with them. But, if investor plans in the sector are largely frozen in the short term, the long-term hope that the reform can transform Mexico's economy is still very much alive.

Editor's choice

More on Mexican reform

- Mexico's banks poised to reap the rewards of new reforms

- Luis Videgaray The thinking behind Mexico's reforms

- Mexico continues its reform drive

- Agustín Carstens looks to keep Mexico on steady path to growth

More on Latin American infrastructure

Part of a wider package of reforms – which also included initiatives to increase competition in the banking sector and open up the telecommunications market – the new rules were designed to boost Mexico’s stagnant economy and reduce consumer costs across the energy, financial services and telecommunications sectors. The financial reform, in particular, has not only increased competition in the banking market, it is also creating new business opportunities for lenders.

“These reforms opened up sectors that were previously closed to financing needs. Banks will need to [provide services to contractors] and their suppliers, both in the energy and telecommunications sectors; this completely opens up the game for lenders,” says BBVA Bancomer’s chief economist, Carlos Serrano. He expects the energy market alone to attract $5bn in foreign direct investment in 2016, which is encouraging for an economy that has grown, on average, less than 2.5% per year in the past decade, and which is expected to expand by a not-much-higher 3% in 2015.

Game changers

Slow economic growth has limited the ability of Mexican banks to expand their loan portfolios, but the growing number of private sector companies involved in energy and telecommunications deals should help on this score.

Loan values will slowly start to pick up this year, according to ratings agency Fitch. Alejandro Garcia, senior director at Fitch, is confident that the reforms are of such significance that they will effect change in the sector, even given the current environment. “[Mexico’s] was such a closed energy sector that even with these oil prices there still is appetite for specific projects,” he says.

Naturally, the large global banking groups that have amassed experience in the energy sectors in other countries will have an advantage over their local counterparts. But Gerardo Salazar, chief executive of local lender Banco Interacciones, sees opportunities for local lenders, too.

“Foreign banks in Mexico are very close to downstream activities in energy – such as the commercialisation of oil derivatives. I see [international] banks participating upstream in the future too, in exploration and production of oil. But the same can be true for domestic banks. They will have opportunities in storing, transporting and refining activities,” he says. Mr Salazar adds that energy-related deals represent about 60% of Interacciones’s project financing portfolio.

Story continues below tables

Opportunities opening up

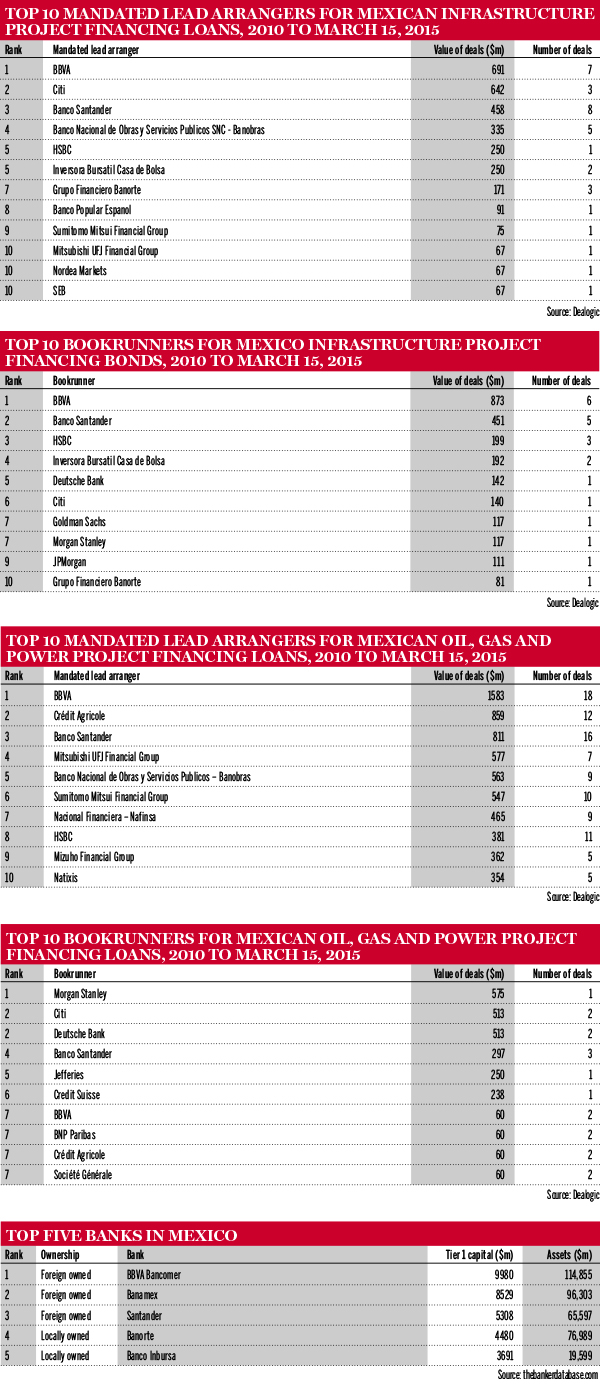

There are other factors that will help contribute to growth in the Mexican banking market in the next few years, such as government infrastructure initiatives to develop the country's roads, ports and airports. Recent infrastructure-related financing deals include transactions as large as the $1bn loan to the federal government to build Mexico City’s new international airport, and the $587m bond issued in 2013 by construction group Empresas ICA to re-finance its RCO Toll Road concession project.

Such deals have already created healthy business opportunities for both local and international banks: Santander, BBVA, HSBC, Banorte as well as Inbursa were on the new international airport’s ticket, while Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, BBVA, Santander and HSBC ran the books on the ICA bond, according to data provider Dealogic.

Furthermore, the financial reform will provide new ways, beside arranging loans and placing notes, for banks to take part of the infrastructure action. By allowing commercial banking holdings to have non-bank assets on their balance sheets, the reform has spurred the creation of infrastructure funds. Banorte, for example, has already jumped at the opportunity, says its chief economist Gabriel Casillas, who expects other banks to create similar structures.

“I hate to call it financial reform because it sounds like more regulation, while one of the big changes is that commercial banks are now able to have [other assets beyond] bank-related assets on their holding’s balance sheet,” says Mr Casillas. “Now, we can put some of [the holding’s] money into the fund, and it’ll be completely separate from the capital of the bank, so we will still comply with Basel III capital rules.”

Risk reward curve

Perhaps more importantly, the financial reform is set to improve access to credit in Mexico, the main aim of the rules being to reduce the cost of borrowing for both businesses and individuals. Banking penetration in Mexico is low, with bank credit to the private sector totalling only about 25% of gross domestic product, compared to Brazil’s 40% and Chile’s 80%. According to Mr Serrano, this is largely owing to the country's large informal sector. “Informal firms do not want to approach a bank and, even if they did, banks would not want to deal [with the lack of data on] credit checks," he says.

High borrowing costs are also an issue. For credit cards – an important source of credit for small businesses – the total cost of credit, including commissions, can go well above 50%, according to Mexican think-tank Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias. In the case of commercial loans, the total cost of credit is about 11% for large firms and 15% for small and medium-sized enterprises.

According to a 2012 survey by the Mexican banking commission, these high costs are owing to the legal transactional costs generated by the bank in the credit process. Lenders in Mexico spend an aggregate 32% of the principal amount of a credit they extend to recover unpaid loans by judicial means. As a comparison, north of the border in the US, this figure is 9%.

Part of the financial reform has involved streamlining the system for recovering credit, which means that things should be changing for the better.

“For commercial banks in Mexico, for example, it takes three years to repossess a home for a mortgage loan that became delinquent," says Mr Casillas. "Right now, [in a legal dispute on a financial matter] you go to a local judge, not a specialised judge; your case ends up in a pile with files for divorce and murder cases. Now [the authorities are] working hard so that there’ll be specialised judges on banking cases. This could become operational at the end of 2016, and could be key to expanding credit to sectors that we haven’t been able [to reach] so far, because of informality.”

Making headway

Some elements of the financial sector reform are already bearing fruit, such as the push to increase transparency around banking fees. The new rules oblige mortgage providers, for example, to clearly disclose the fee component of the mortgage cost to clients, and allows the consumer to change provider more easily and cheaply.

Banco Inbursa’s head of credit risk, Frank Aguado, says: “We’re already seeing results of increased competition for mortgage business, with [customers able to switch between providers more easily and cheaply]. Our mortgage area has grown in December alone by about 200m pesos [$12.97m] pesos, and this was mainly related to [existing mortgage holders switching to Inbursa] rather than origination.”

Alternative banking channels will also help to increase banking penetration in the country. Inbursa, for example, has teamed up with Banamex and telecommunications provider Telcel to create its mobile payments platform, Transfer. Other lenders are doing the same. Mobile banking has the potential to boost the reach of smaller lenders, which do not have the same bricks-and-mortar presence as the larger, more dominant players.

Luis Niño de Rivera, vice-chairman of Banco Azteca, a Mexican lender that focuses on mid- to low-income customers, says: “At Azteca, we have invested quite a bit of money in technology and mobile channels, but we still have less than 30% of our clients using mobile banking. This probably reflects the ratio for the whole of the banking sector. Mobile banking usage is very low compared to [developed] markets, but it’s improving fast. More Mexican banks are developing more products and services in that direction.”

Competition hotting up

The financial reform is certainly encouraging competition in Mexico’s banking sector, where top lenders claim large shares of the credit market, and technology is only going to speed up this process. “Competition is getting steeper,” says Mr Niño de Rivera. “With the advent of more technology, the playing field is levelling out for those who want to invest in products and services, for those banks that become more valuable to consumers.”

The combination of new financial rules, the growing use of technology and new business opportunities ranging from the energy sector to transport infrastructure look set to create a more lively, and fairer, banking market in Mexico.